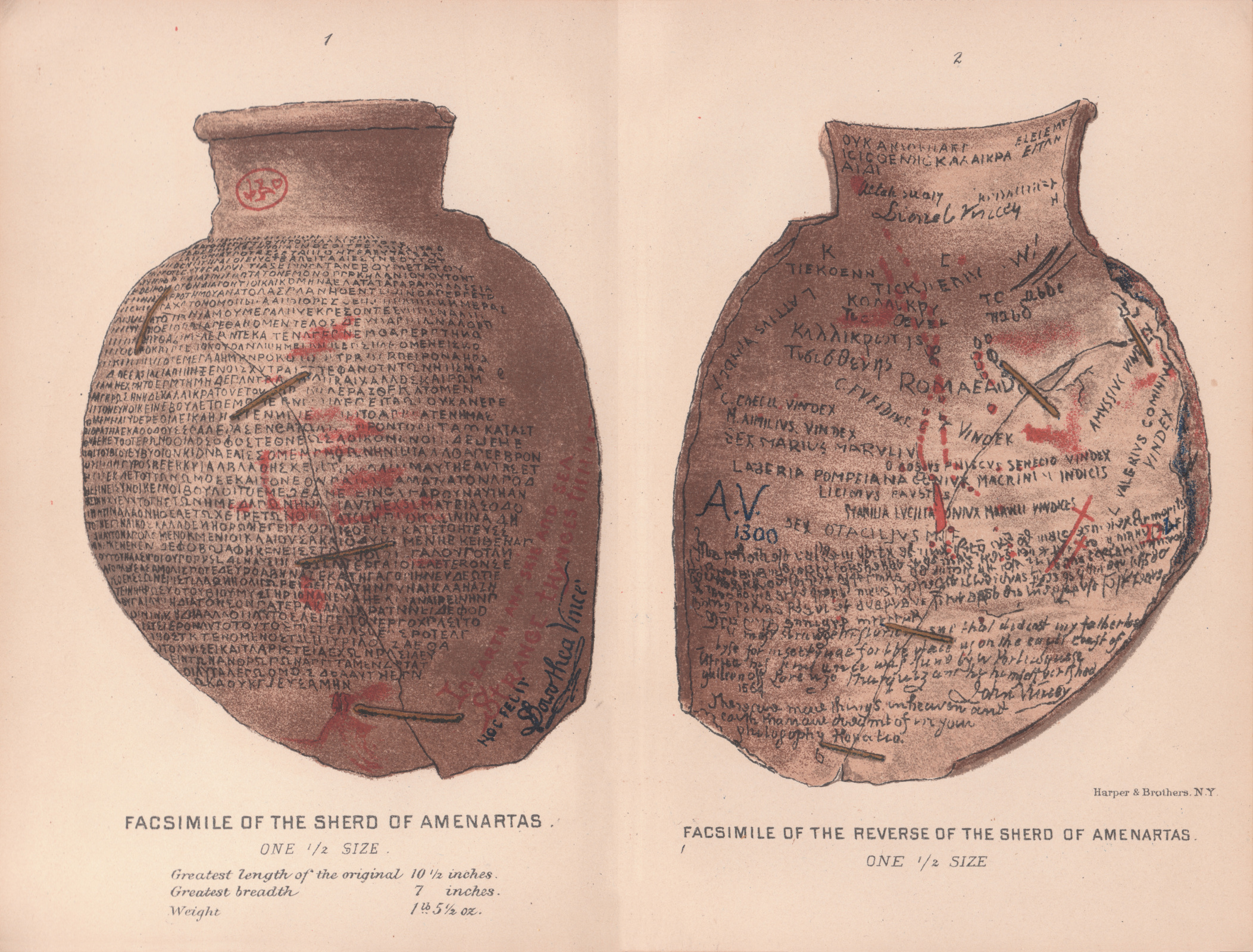

Figure 1. An illustration of a fictional artifact from H. Rider Haggard’s She: A History of Adventure. Image used with a Creative Commons license from VisualHaggard.org.

One of the challenges of teaching literature in a multimodal communication course is to keep students focused on the task at hand—becoming effective communicators—while also teaching the literary work as an artifact with all its history, cultural significance, and metaphorical complexities. While I think nearly any cultural artifact from an ancient drum to a Romantic painting to a Dan O’Brien poem could be useful in a multimodal communication course, some artifacts are perhaps more naturally suited to this purpose than others.

Figure 2. A literal cliff hanger. Image used with a Creative Commons license from VisualHaggard.org.

I recently discovered one such work in a course featuring nineteenth-century artifacts of British imperialism. H. Rider Haggard’s novel She: A History of Adventure follows a small group of men as they leave England and embark on a journey to find a mysterious and beautiful white queen ruling in Africa. I chose the novel because it highlights Victorian perspectives on race and gender when Britain was nearing the height of its power, and I thought that it would illustrate to students how popular culture played an important role in creating and perpetuating racist and sexist attitudes during a period of incredible imperial expansion. I did not, however, predict how well this novel would get students thinking about multimodality and their own authorial intention, structure, and audience.

Haggard constructs his “history of adventure” with a frame narrative that’s designed to make the novel feel “real”—that is, crafted to make the text seem like a legitimate recording of history rather than a fabricated work of adventure fiction. He presents himself as merely the editor of an extraordinary tale that he presents unaltered to his readers complete with illustrations, facsimiles, letters, footnotes, and archeological evidence (see fig. 1). One student, Fatima Jamil, described these paratextual elements as visual and verbal “deceptions” that seek to “induce belief in the unbelievable.” Haggard’s tale is certainly far-fetched (a woman who has lived for two-thousand-odd years has the power to kill by simply pointing her hand), so we might argue that these deceptions are necessary to capture an audience’s attention. It also strikes me, though, that any time we construct an argument, we try to do what Jamil describes—we try to “induce belief”—so we carefully craft an essay, presentation, or film that goes out of its way to convince our audience that our position is valid. Unless we are creating fictional works like Haggard or, perhaps, running for president, we don’t categorize these attempts as “deceptions,” but like Haggard we do carefully consider our rhetorical situation and how we can create works that capture and retain our audience’s interest.

Figure 3. Fatima Jamil analyzes Haggard’s paratextual features in her own intentionally designed essay.

Students recognize right away that Haggard’s attempts to legitimize the story are a bit excessive, but Haggard’s decision to include these paratextual elements helps them think through how different modes work together to create meaning and how a communicator can effectively utilize the affordances of a particular medium for his or her own purposes. In Haggard’s case, he packages his fantastical story in order to retain an audience over weeks of serialization (the novel was published in installments in the Graphic from October 1886 to January 1887). He includes a literal cliff hanger, for instance (see fig. 2), and adds footnotes with historical or geographical information that make the far-fetched tale seem grounded in reality. Students see how Haggard curates an experience of the story for his readers that gives the book a feeling of authenticity. In their own compositions, then, they feel challenged to do something similar as they design their work. Jamil reflected on the process of writing an essay on the novel saying, “My composition process included thinking about how my audience would perceive my text, rather than only thinking about my ideas about the novel. I had to think about these two aspects simultaneously, instead of disregarding the visual design aspect.” Jamil’s essay (see fig. 3) exemplifies the kind of critical thinking we want to see in a multimodal communication class; she not only developed a compelling literary analysis, but she also designed a document that is engaging and professional and that works in tandem with her argument to make it convincing.

While Haggard is hardly a household name, his adventure novel offers us a chance to examine how a multimodal artifact functions and can inspire students to critically examine their own composition process. I suspect that other texts that draw attention to their constructed nature could offer the same.