Postcard of Wivenhoe, Essex, England looking over River Colne, sent by Ted Berrigan to Bill Berkson, 1974. Courtesy of University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections.

“Wake up high up / frame bent & turned on,” begins Ted Berrigan’s iconic “Things to Do in New York (City),” a lyric list poem that shows Berrigan moving through the literary landscape of the city in timeless style. Berrigan was fond of this genre, also writing poems like “Things to Do in Bolinas” and “Things to Do in Providence” that map a New York School sensibility onto the geographies of his life. These poems are useful access points for students to consider how poetry and place intersect, and how thinking about place, especially exact locations, can help us to ask new questions about the books we read.

In my ENGL 1102 course this semester, “Teens, DIY, and the Avant-Garde,” Jim Carroll’s coming-of-age memoir The Basketball Diaries, which is dedicated to Berrigan, is one of our primary course texts. Recently, students spent a class session mapping locations from Carroll’s memoir by using Google My Maps to visualize how the events of the text, restricted mostly to the island of Manhattan, might develop into a new set of visual and spatial relationships. Students plotted close to 100 locations from the book, identifying each location with its reference from the text. With our collective map now assembled, students discussed how the map allowed them to describe the novel in different ways, especially how it revealed Carroll’s narrator’s lengthy commutes up and down Manhattan and the density of activity in the borough, which when seen on a map, reminded them that New York City is actually a lot bigger than Manhattan by itself. While the current formatting of the map was designed simply to identify as many locations as possible during class, students offered alternative methods for organizing the visual data, like comparing a series of maps associated with different activities central to the book’s narrative of addiction, sexuality, crime, and artistic growth, or even creating different maps that track where the narrator buys and does different drugs, creating a youth addicts’ map of mid-1960s Manhattan. For example, seeing a visual correlation between characters’ desire “to go to the East River Park and get drunk, do reefer, and sniff glue” with a spot in Upper Manhattan where Carroll and his friends “nod” on heroin creates layers of unique correspondence between locales of male adolescent experimentation and more serious drug use. New York School texts like The Basketball Diaries, Eileen Myles’s Chelsea Girls, and Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day, each full of various narratives of movement and spatial relationships, are ideal opportunities to experiment with this literary mapping process.

Looking further at the map they created, students saw other correlations among the scattered pins. Interestingly, the two most notable outlying points of events in the text—the Statue of Liberty National Monument and Rikers Island—revealed that the memoir is actually populated by activity on three islands, not just the island of Manhattan, and that these two outlier locations frame the protagonist’s uncertain movement between freedom and imprisonment throughout the book. On a symbolic level, the map showed that it’s possible to view Carroll’s Manhattan as a landscape of good and evil where the downtown, Lower East Side “hell” contrasts with the Catholic, Upper Manhattan “heaven” that the narrator constantly toggles between during the moral and aesthetic events of the memoir. This process was clarifying for students who hadn’t found opportunities to consider these readings when encountering the written text. Especially students who had visited New York City in the past were surprised by how searching and pinning locations on the map gave the more outlandish, uncomfortable events of the text a real-world texture. Encountering the events of the book as happening in actual places rather than the abstract, fictional space of a text, students suddenly found themselves aligned with Carroll’s narrator based on their own familiarity with the city via the near-ubiquitous digital surface of Google Maps.

In the another poem by Ted Berrigan, “So Going Around Cities,” a Whitmanic ode to friendship and the intimate exchanges of being that compose a life, Berrigan catalogues the names of streets he and his family—including his wife, the poet Alice Notley—lived on while “going around cities,” including New York City; Southampton; Chicago; Bolinas, California; and a small English village called Wivenhoe: “Taking walks down any streets, High / Street, Main Street, walk past my doors! Newtown; Nymph Rd / (on the Mesa); Waveland / Meeting House Lane, in old Southampton; or BelleVue Road / in England, etcetera.” For a literary scholar who commonly uses geocriticism—as described above, the process of mapping spatial and geographical relationships in texts—to offer students hands-on, visual and digital processes to develop competencies with challenging books, Berrigan’s call to “walk past my doors” is a tempting invitation to trace his movements across a personal and aesthetic landscape of real locations. In fact, earlier this semester after reading Berrigan’s The Sonnets, a student had responded to a question asking them to index lines from the poems based on identifiable themes or concepts by indexing all of the lines from the sonnet sequence referring to New York City: “It’s 8:30pm in New York and I’ve been running around all day”; “feminine marvelous and tough / watching the sun come up over the Navy Yard”; “And high upon the Brooklyn Bridge alone”; “I think I was thinking when I was / ahead I’d be somewhere like Perry Street erudite / dazzling slimmed and badly loved”; and so on.

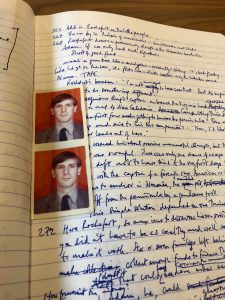

Photo of Douglas Oliver in one of his notebooks. Courtesy of University of Essex Special Collections.

Berrigan’s time in England, where he and Notley lived in 1973-74 while teaching at the University of Essex, seems to have been especially on his mind while composing “So Going Around Cities.” Not only is the poem dedicated to English poet Douglas Oliver and his wife Jan, “My English friends, whom I love & miss,” as Berrigan writes, but Notley and Berrigan’s son Edmund was born in England in 1974, the occasion for Notley’s book-length poem Songs for the Unborn Second Baby that was composed in Wivenhoe, and Oliver, then a graduate student in Literature at Essex (in Colchester just a mile and a half from Wivenhoe), would later end up marrying Notley in 1988 following Berrigan’s death in 1983. “So Going Around Cities” is Berrigan’s own divining map of the intersections between place, memory, friendship, and love, showing him tracking some of his most honored relationships in the poem’s exquisite care and honest, warm music. One of my goals teaching the writers of the New York School at Georgia Tech is to show students how these personal correspondences between artists develop into an intertextual aesthetic conversation. But rather than use Google Maps to track the geographic relationships in the poem, why not take up Berrigan’s invitation to “walk past [his] doors” and explore the living architectures of those locations?

I had exactly that opportunity this summer while traveling to the UK for a symposium, “New Work on the New York School,” at the University of Birmingham. (See my article “Multimodal Art House @ Tech: Researching the New York School with First-Year Composition Students” on the symposium blog.) Hosted by the American and Canadian Studies Centre at the University of Birmingham, the one-day conference was an exciting panorama of scholarship and creative work featuring many younger and early career scholars. My invitation to the symposium was the opportunity to debut my digital publishing project “Alice Notley’s Magazines,” an online archive that seeks to make available fully searchable facsimile PDF editions of the poetry magazines edited by Notley, two of which, Scarlet and Gare du Nord, were co-edited with Oliver. Like “So Going Around Cities,” my time in England ended up being a serendipitous alignment of personal, aesthetic, archival, and historical threads, those generative spaces that make my work as a scholar and educator so energizing and idiosyncratic. Not only did I have the opportunity to stay in Wivenhoe for a few days to trace Berrigan’s presence in the town, but Notley herself was in attendance at the symposium with her son Edmund Berrigan, and between moving back and forth from Wivenhoe to Birmingham, I was able to spend a day in the Douglas Oliver Archive at the University of Essex. Thanks to the generous support of the Writing and Communication Program, School of Literature, Media, and Communication, and Poetry@Tech, what started as an invitation to a conference turned into a somatic, scholarly, and pedagogical layering of presence and activity, experience and thinking, past and present.

Rather than a traditional essay, what follows is a day-by-day travelogue-in-fragments of that trip to Birmingham, Essex, and Wivenhoe this summer. As Alice Kaplan describes in her essay “Working in the Archives,” which I think applies equally to the experiences of reading, imagining, and composing in the composition classroom, “The best finds in the archives are the result of association and accident: chance in the archives favors the prepared mind.” These entries are my alignments of association and accident, a case study in how our interests and devotions to what we study—regardless of discipline—can begin to light up in unexpected ways that are both movingly personal and intellectually speculative. I’m also thinking of this as a model for how students can respond to their interactions with texts across time by composing diary-style entries that follow both their physical movements (through Atlanta, across campus) with their intellectual movements (across books, through authors).

29 BelleVue Road, Wivenhoe, Essex; where Notley and Berrigan lived 1973-74. Photo by Nick Sturm.

July 4: Saw the house at 29 BelleVue. “This house,” Alice writes, “rented from a man named the Reverend Lovelace, had an immense English garden in the back with three–was it more?–apple trees, a sepulchre-shaped compost heap, lots of rose bushes, herbs, lots of new flowers blooming monthly, a shed, a bomb shelter.” The bells rang all evening. Ted’s line “a pile of old birds” echoing over the Colne River. I’m sitting in front of the Rose and Crown listening to Ted read at Naropa, August 1979, “Last Poem,” and others. He died today 35 years ago. This year I’ll be 32. Carrie, too. Flowers lush everywhere.

July 5: A day with Douglas Oliver’s archive in the Albert Sloman Library at the University of Essex. I was left totally alone in the reading room, except a pigeon cooing/murmuring/dreaming above me outside the window. Alice will tell me later, “I read all of the poetry books in that library that Tom Clark hadn’t already stolen.” Doug’s notebooks full of Virgo attention to the magic of detail and repetition. “Politics begins then in this pink desert,” “Self as shining,” “Don’t forget the ritual.” On one page he’s just scribbled, in the upper left hand corner, “Clairvoyance.” Afterwards the train to London to Birmingham for symposium. First time seeing the fields of lavender. I buy more groceries than I need from Asian market because the idea of making dinner after traveling is frantic and amazing.

“Your only problem / he tells me / is excessive rage.” — from Songs for the Unborn Second Baby by Alice Notley. Photo by Nick Sturm.

July 6: Weird industrial Birmingham like it’s been puzzle-scraped together. Realize as soon as I’m home teaching again that Birmingham is where the two men take her into the cemetery in Schizophrene by Bhanu Kapil, a book we’re reading for class, that I’ve taught so many times. Before I know this I don’t see any cemeteries but “remember” them now, actually a school field. Conference goes all day. Older New York School scholars are protecting something and won’t admit it or can’t see it or aren’t listening. RC confronts MF, who is there, in her paper and “wins.” Three or four of us acknowledge this victory in a cab later and laugh which is our dissertation. See Eddie in the hall and we’re eating pastry. Then Alice walks up, recognizes me, handshake, now we’ve met but we’re in some sort of manor house museum cafe upstairs for this conference, it’s so hot and there’s a view and American I’m sitting right in front of the one little fan. Later Eddie, Alice, and others read in an old theater with dark green seats and walls like 1970s living room but public. Alice reads newer works and also “Sept 17 / Aug 29, ’88” from Mysteries of Small Houses about her brother in Vietnam, she tells me later, “because that’s also the New York School,” a comment directed at how everyone, including us today, keep making the New York School into a particular thing. Then we’re in a cab back to the hotel, Alice offers strawberries blueberries too I think and “Sit down eat this” and incredible story about arriving in the room earlier to find no drinking glass. “There wasn’t a glass how am I supposed to drink the water” and yelling through the wall. Down to street for drinks with Eddie, we sit together and devolve.

July 7: Breakfast with A and E but not until we walk around city center not finding anywhere to eat breakfast and A says “Guys I don’t think I can do this” and then we’re in the train station, there’s juice there’s coffee there’s sandwiches. Questions. Stories. We’re talking about ourselves now the past and about Wivenhoe. What was said? A story about a dinner with Doug and Jan. Other fragments I’ll gather later. More a feeling for it and that we like each other. E + I am wearing the same color T-shirt same pants. Pictures in front of the hotel and I look back through the window to my own room and leave. Riding the train back to London it’s noon Pride Day and a thousand sequined parade-goers are flashing through the station undoing the undragged day when England (World Cup) scores a goal against Sweden and entire station erupts in cheers I’m just tired and hungry and happy for everyone. Back in Wivenhoe everything is in place and warm slow soft and flowers. Alice writes in Songs for the Unborn Second Baby, “I am a citizen / of this garden.”

Colne River looking towards the Quay, Wivenhoe on the right shore. Photo by Nick Sturm.

July 8: Day to be completely in Wivenhoe. I eat only fish & chips all day I’m elated. I’m at The Black Buoy most of the last 36 hours, same pub as was there in ’73-74 and 250 years before then it seems, or that’s how they tell you. Alice said, “Is the The Black Buoy still there?” “Yes.” I’m reading Doug’s Whisper ‘Louise’ his wonderfully obscure “double historical memoir and meditation” of himself and 19th century French Communard Louise Michel, published posthumously in 2005. I love how honest and disagreeable the prose turns, he’s insisting. It is full of this layered excessive intelligent feeling and telepathy. “Ted and Alice’s unremitting poetry-life together, with all its hardships, had left an aftermath of itself in their tiny Manhattan apartment where I now lived: a sense of better purpose; and my stepsons shared its beliefs. This has affected the rest of my life.” Suns down on the Colne, the day sheds.

July 9:

Valentine comes to his cabinet, and opens it.

As into air the purer: Is that machine

ready to start? My absolute last cup of coffee

undazzled at noonday, but dearest, of so short a stay

his mother a burning mountain, linear and dwindling, we went into

The Hamburger Hamlet as well as the white rose

and drank the crystal stream. What wanting signs are those?

Spirits flow, now, like the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland.

On books aglow, galleries and, briefly, crab cakes.

With my magic opal my murderers around me stood.

A lily of a day, like an art-perspective exercise,

pointing upward, makes for his door.

Some copies of a new book are on the desk:

This breathing house not built with hands.

I don’t know who is doing the blackmail, but

I so seldom feel wicked, rich, prime–reading

old things, and Valentine poured some more.

If I’d gotten a chance to dance. Sure. Yes. In part

is too precise in every part. The Flower Girl:

I didn’t. And quickly steal the rest.

[Poem made from lines/phrases from three books on the shelves in my Airbnb my last morning in Wivenhoe: Collected Works of George Bernard Shaw (on whom Berrigan wrote his Master’s Thesis), Oxford Book of English Verse, and a pulp detective novel called, appropriately, The Widening Gyre, a genre loved by Ted and Alice.]

Works Cited

Berrigan, Ted. The Sonnets. New York, Penguin Poets, 2000.

Kaplan, Alice. “Working in the Archives.” Yale French Studies, no. 77, 1990. pp. 103-116.

Notley, Alice. “Doublings.” The Grand Permission: New Writings on Poetics and Motherhood, edited by Patricia Dienstfrey and Brenda Hillman, Wesleyan University Press, 2003, pp. 136-143.

—. Songs for the Unborn Second Baby. Lenox, Massachusetts, United Artists, 1979.

Oliver, Douglas. Whisper ‘Louise‘. East Sussex, UK, Reality Street, 2005.