Not long before the Primitives changed their name to the Velvet Underground, the band’s singer, Lou Reed, wrote to his Syracuse University professor, poet Delmore Schwartz,

I decided that I’m very very good and could be a good writer if i work and work. i know thats what ive got to do, no getting around it, but things had to get established, maybe i will go to school again. maybe i’ll teach, maybe europe, who knows. But mainly it must be writing and I think I’m good enough to give it a run for its money. (qtd. in Kane 66)

In “Do You Have a Band?”: Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City (2017), Daniel Kane reads this letter as a proverbial “son (Reed) beseech[ing] the wise father (Schwartz) to pass on the poetic baton” (66), in the effort of showing not only how “musicians such as Reed and [Patti] Smith conceived of themselves initially as poets and were determined to embody poetic genius and vision,” but also “what happened when Smith and the rest of this cohort were confronted with second-generation New York School poets (14).” Anne Waldman, Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, and Bernadette Meyer all lived, wrote, and read in the environs of the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, just ten blocks from CBGB, the much glamorized venue where first-wave punk bands such as Television, the Ramones, Blondie, and Talking Heads gained early notoriety. Digging through the archives of Reed, Smith, the Fugs, Richard Hell, John Giorno, Eileen Myles, Dennis Cooper, Jim Carroll, and others, Kane shows beyond a reasonable doubt that poetry and punk rock were overlapping, mutually influential scenes in the lower Manhattan of the 1970s.

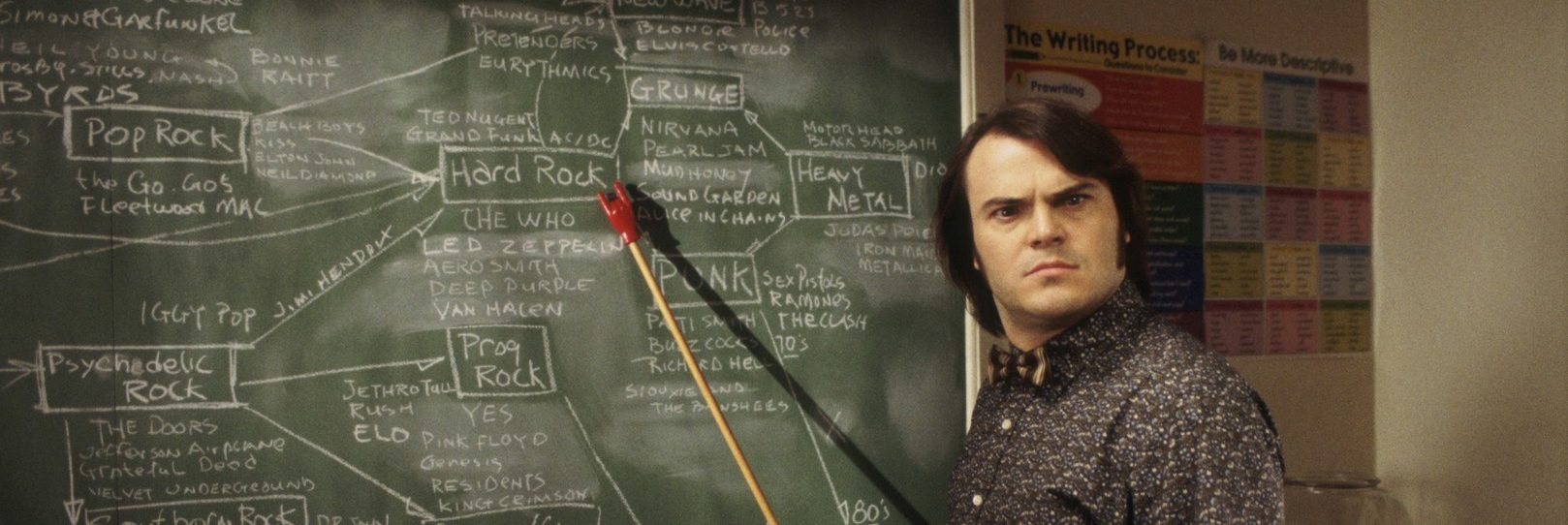

Even so, Bob Dylan’s 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature has yet to kill off the academic tendency to leave poets slinging guitars out of Norton anthologies, and with them, literary history. This is undoubtedly due, in part, to the fact that school and rock music appear on the surface to be polar opposites. Despite the scholastic accomplishments of punk rockers from the Velvets’ Sterling Morrison (Ph.D. in Medieval Studies, University of Texas at Austin, 1986) and the Descendents’ Milo Aukerman (Ph.D. in Biology, University of California, San Diego, 1992) to Bad Religion’s Greg Graffin (Ph.D. in Zoology, Cornell University, 2013) and the Offspring’s Dexter Holland (Ph.D. in Molecular Biology, University of Southern California, 2017), this binary is solid enough that an entire subgenre of film, of which Roger Corman’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1979) is perhaps the best example, rests upon it. Is a college course about punk necessarily “un-punk,” as I have been told countless times at house shows, DIY spaces, dive bars––and even by my own students?

As an academic who has long moonlighted as a musician and songwriter, a critic for venues both “pop” and peer-reviewed, I have struggled at times to reconcile my desire to create with the impulse to critique. But for the most part, I see my work in music and higher education as coming from the same urge––to enlighten, as well as to resist. Or, as Greil Marcus puts it in Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century (1989), to negate: an “act that would make it self-evident to everyone that the world is not as it seems––but only when the act is so implicitly complete it leaves open the possibility that the world may be nothing, that nihilism as well as creation may occupy the suddenly cleared ground” (8). “Negation is always political,” Marcus writes: “it assumes the existence of other people, calls them into being” (8). Negation is what John Keats refers to as William Shakespeare’s “negative capability” of “being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason” (277), but also what F. Scott Fitzgerald means when he writes that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” Shakespeare, Keats, and Fitzgerald were all punks in their own way, and not (only) because they died young: rather, they remained unimpressed by the truths set before them. They wanted something else––something more, something louder. So they did it themselves.

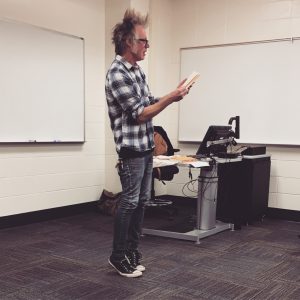

Unsurprisingly, the first-year writing course that I taught about punk last fall (officially called “English 1102: The Multimodal Language of Punk Rock,” which one student, Hannah Dailey, rightly notes is “a title that any ‘punk’ would likely abhor”) brought a number of pedagogical firsts and highs. Thanks to generous funding from the Honors Program, I was able to take my students to see the Descendents play the storied (if recently relocated) Atlanta venue the Masquerade––for some, their first rock concert. This involved ushering 17 post-adolescents to and from downtown Atlanta on Saturday night public transportation, and warning them in an email a week before the show, “This goes without saying, but drugs are illegal, and booze is only for those 21+, so please keep that in mind.” Some students approached the concert with journalistic professionalism (they were tasked with writing a review of it for a publication of their choice), others leapt towards the stage, and at least one of them transformed into a crowdsurfer by the end of the night. Two weeks later, poet, teacher, and musician Matt Hart spent the day with my students and me, prior to his Poetry@Tech reading. He screamed re-writings of Apollinaire at them until his face turned red (his visit to my colleague Nick Sturm’s class the previous day resulted in shushes from the instructor next door), upsetting their expectations of a poetry reading, just as Aukerman had alerted them to punk’s transcendent powers from the stage of the Masquerade: “Cancer sucks!” he proclaimed, introducing the Cheifs, whose founding bassist had died earlier that week. That a group of balding men in their fifties could command the admiration of a room of hundreds with silly paeans to caffeine proved as astonishing to them as a respected, widely published poet citing Black Flag as an influence.

Hart and the Descendents, memorable though they are, were no more impactful than the students’ contributions to the conversation. As we read Lipstick Traces, we took to Twitter to discuss Situationist and punk détournement in the context of meme culture; my students practiced détournement themselves, making cut-ups and erasures, compiling them into zines. In my own work, I’ve always been attracted to Marcus’s big, transhistorical arguments––which, in the case of Lipstick Traces, filiates the Sex Pistols with Dada, the Situationists, medieval heretics, and others. A representative passage finds pedagogical precedent for punk rock in the work of philosopher-critics Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Walter Benjamin:

punk was most easily recognizable as a new version of the old Frankfurt School critique of mass culture, the refined horror of refugees from Hitler striking back at the easy vulgarity of their wartime American asylum; a new version of Adorno’s conviction, as set out in Minima Moralia, that as a German Jewish intellectual in flight from the Nazis to the land of the free he had traded the certainty of extermination for the promise of spiritual death. (67)

Likely because they hadn’t spent years in humanities graduate seminars, as I have, the students were less eager than I to locate the roots of punk in Weimar coffeehouses or modernist bungalows in the hills outside Los Angeles––though they were sympathetic to the idea that punk is not isolated to the 1970s, but lives on, is passed down.

One must look no further than Smith’s own memoir-elegy to Robert Mapplethorpe, 2010’s Just Kids––students’ favorite book on the reading list, by a wide margin––for models of a punk pedagogy. From the very beginning, Smith––the “punk poet laureate” who first performed at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project in 1974, with Lenny Kaye on guitar––is full of praise for her teachers: her mother, who taught her to read; the teachers whom she “vexed” with her “precocious reading ability paired with an inability to apply it to anything they deemed practical” (9); and the “benevolent professor” who “found an educated couple longing for a child” when Smith became pregnant at age 20 while studying to become a teacher herself (18). Smith praises Beat Generation writers Gregory Corso, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg as her “teachers, each one passing through the lobby of the Chelsea Hotel, my new university” (138)––despite the latter’s initial attempt to pick her up, mistaking her for “a very pretty boy” (123). Most of all, though, she praises her onetime boyfriend, playwright and actor (and drummer of the Holy Modal Rounders) Sam Shepard, for teaching her “the secret of improvisation, one that I have accessed my whole life” (185). When Smith and Shepard were writing the play Cowboy Mouth, which they performed in April 1971, Smith “got cold feet” when faced with improvising “an argument in poetic language” (185). “I can’t do this,” she told Shepard, “I don’t know what to say.”

“Say anything,” he said. “You can’t make a mistake when you improvise.”

“What if I mess it up? What if I screw up the rhythm?”

“You can’t,” he said. “It’s like drumming. If you miss a beat, you create another.” (185)

Here, Shepard provides Smith with a fundamental lesson in negation: that her insecurities are illusions; the only way to overcome them is to throw them out the window. I think that students, for whom writing can be so intimidating, had a similar realization when Hart told them that he had written at least one poem every day in 2017, not allowing himself to look back at any of them until the next year. One of punk’s most famous mantras––this is a chord, this is another, this is a third, now form a band––echoes proto-punk Ginsberg’s Beat philosophy of “first thought, best thought,” which Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac learned from the bebop improvisations of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and other jazz musicians of the 1940s. As a style, a movement, an attitude, or a way of being, punk may not be taught so much as it is learned––which begs the question, “why not?” This question––behind Iggy Pop’s stage antics, the New York Dolls’ crossdressing, the punk appropriation of the swastika, or Hell’s mythical “Please Kill Me” t-shirt, which gave Legs McNeil’s and Gillian McCain’s classic oral history its name––is perhaps the most punk rock question ever asked, and one of my primary motivations for teaching a writing course about the topic at Georgia Tech, where the rigorous STEM curriculum and culture of professionalization often stand in stark contrast with the radical expressions of individual liberty usually associated with punk (excepting Tech’s excellent radio station, of course).

Matt Hart reads to English 1102: Punk. Photo by Andrew Marzoni.

“Why not?” is a question that points to one of the aesthetic qualities most commonly called upon to bring together punk’s disparate sub-cultures and -genres: irreverence. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “irreverence” as an “absence or violation of reverence; disrespect to a person or thing held sacred or worthy of honour,” but it can also be identified in what Hart refers to as the Sex Pistols’ “good/bad humor, their negativity and snarky-ness, their ferocity and electricity, their willingness to throw themselves to death against the wall—to turn themselves inside out, exposing the muck of human being in ridiculous and self-destructive terms.”

Of course, “the muck of human being” is something few Americans need reminding of in 2018––one must only glance at the president’s Twitter feed to witness humanity’s tendency toward the ridiculous and self-destructive. In some ways, Trump is our first punk president, a master of the rhetoric of negation: he entered the political arena by negating Barack Obama’s legacy and legitimacy, and the engine of his campaign was negating Hillary Clinton’s. Yet, with such disrespect, negativity, violation, and snark warming the seat of what was, for some, the nation’s most honorable station, what better time is there for thumbing one’s nose at the thumb-noser-in-chief, throwing oneself against whatever walls exist, as well as those yet to be built?

Arguments have been made that punk’s necessarily oppositional stance, its potentially solipsistic privileging of the amateurish and the nihilistic, are part of the problem rather than its solution. In his 2016 film HyperNormalisation, British documentarian Adam Curtis blames the rise of the Trump Organization (and with it, the hypergentrification of New York City and Ronald Reagan’s election to the White House in 1980) on the “retreat” of the American Left into artistic expression rather than political action, following the demise of the utopian dreams of the 1960s––the very historical conditions which gave birth to punk rock. And Angela Nagle, in Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right (2017), chronicles how the “online politics of transgression” practiced by the trolls who made Pepe the Frog a symbol of hate and Trump the leader of the free world has its roots in the “Nazi flirtations” of the Sex Pistols, Joy Division, and Siouxsie and the Banshees (28-9; it certainly doesn’t help that John “Johnny Rotten” Lydon has expressed support for “possible friend” Trump). In its more nefarious manifestations, negation can resemble little more than trolling, an ironic distance hardened into cynicism––or worse.

While there is truth in these accounts and it is inarguable that rock music’s politics have been problematic since its beginnings (see, for example, Lester Bangs’s 1979 Village Voice essay, “The White Noise Supremacists”), it is difficult not to read the persistence of punk rock’s resistance––against racism, sexism, homophobia, censorship, fascism, conventional wisdom, and good taste (to name a few)––as an active agent of social justice and change. The learning outcomes for first-year writing courses at Georgia Tech ask that students come to “understand relationships among language, knowledge, and power,” “recognize the constructedness of language and social forms,” and “analyze and critique constructs such as race, gender, and sexuality as they appear in cultural texts”––all of which could more or less be accomplished through a close reading of the Clash’s 1979 LP London Calling, as student Rachel Fallon did with great success.

Above all, it was in awakening students to the power of resistance as their intellectual right that I relished the most. As TECHStyle co-editor Anna Ioanes wrote in December 2016, “when we approach conversations about the election or other contentious topics as a neutral exchange in which each statement is intellectually and morally equivalent, we don’t just make some students feel more or less safe; we construct conversations that produce knowledge.” Asking “why?”––or “why not?”––is one of a child’s most formative cognitive advances towards adolescence, and when it comes to their studies in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, a question they pose without fail. By encouraging students to negate the world––to be against it, even––we teach them to think critically, sort fact from fiction, communicate, and hopefully, empathize. “‘Punk,’ is,” Dailey writes in her final essay for the class,

more than anything, an attitude towards living. Punk artists as we know them express this attitude through music, but ultimately, “punk” is the idea that self-expression trumps all. Sometimes this self-expression has some greater purpose, like pointing out the flaws of society, and sometimes this self-expression is just for the sake of self-expression.

Looking to the future, Dailey concludes, “As I go throughout the rest of my college career and my life, I will always carry a bit of this punk wisdom with me: self-expression trumps all, and it should be sought by any means necessary.”

Rock and roll.

Works Cited

Curtis, Adam, dir. HyperNormalisation. BBC, 2016.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. “The Crack-Up.” Esquire, Hearst Communications, Feb.-Apr. 1936, http://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/a4310/the-crack-up/. Accessed 23 Jan. 2018.

Hart, Matt. “By Any Means Necessary: Part 1.” Coldfront, Coldfront Magazine, 1 May 2011, http://coldfrontmag.com/by-any-means-necessary-part-1-by-matt-hart/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2018.

Ioanes, Anna, et al. “Meditations in an Emergency: Teaching After Trump.” TECHStyle, Georgia Tech Writing and Communication Program, 13 Dec. 2016, http://techstyle.lmc.gatech.edu/meditations-in-an-emergency-teaching-after-trump/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2018.

“irreverence, n.” OED Online, Oxford UP, Jun. 2017, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/99819/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2018.

Kane, Daniel. “Do You Have a Band?”: Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City. Columbia UP, 2017.

Keats, John. “Letter to George and Thomas Keats.” The Complete Poetical Works of John Keats. Houghton Mifflin, 1899. 276-77.

Marcus, Greil. Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century. Harvard UP, 1990.

Nagle, Angela. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Zero, 2017.

Smith, Patti. Just Kids. Ecco, 2010.