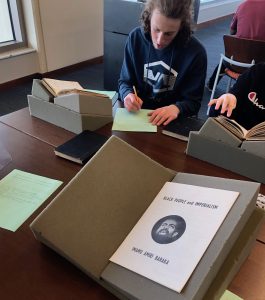

Spelman students at Rose Library with Instruction Archivist Gabrielle Dudley. Photograph by Courtney Chartier.

Teaching with Primary Sources at Georgia Tech and Emory University: An Introduction

Teaching with primary sources is central to my pedagogy as an instructor at Georgia Tech, where I’m a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow, and Emory, where I’ve taught as Visiting Faculty in the Creative Writing Program. I’m fortunate to have access to both Georgia Tech’s Archives and Special Collections and Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, as well to opportunities to collaborate with the curators, archivists, and staff who facilitate access to these collections. My students at both institutions regularly visit the Rose Library for research projects and creative exercises, like studying translation practices in New York School little magazines in the 1960s, and engage with innovative archival environments at Georgia Tech such as retroTECH where students recently digitized a vinyl record of an Atlanta folk singer to use in a podcast. Students are amazed at their ability to interact with these primary sources in an array of mediums that are exciting and surprising to them. Sometimes that means studying early 20th century campus maps or playing an early version of the computer game Diablo on a 1990s Mac. Other times that means reading through a poet’s personal journals or seeing drafts of a poem they’ve read in its published form. In either case, these are experiences of intimate connection. Especially when using the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library at Emory, an inexhaustible living library of poetry from the 20th century, students are astounded at how “real” and “raw” their experience can be. “I think experiencing art like this in a more humble, less edited, less consumerist form allows the art to hold you,” writes Sophia, one of my creative writing students at Emory. “It feels so much more like a one-on-one personal experience.”

Students from Georgia Tech at Emory’s Rose Library. Photograph by Nick Sturm.

Bringing my students into the archive as an instructional environment is a natural extension of Georgia Tech and Emory’s innovative shared collection of library resources, an institutional collaboration embodied in the new Library Service Center that allows the entire circulating collection of both universities to be accessed by everyone at both schools. Students at Tech can now request books directly from the Emory Shared Collection via our online catalog, a process that helps them understand the library as an accessible part of the infrastructure of their undergraduate education. Taking the next step and visiting the Rose Library further cements this process of discovery and research. As my Georgia Tech student Asier recently wrote after a visit to the Rose Library, “I learned about a different way of researching the humanities which relies not so much on coming up with a question and then looking for answers, bur rather looking for questions and answers in a parallel way. It’s not a linear way of research but more like a web of information.” Asier’s description of primary source research as an iterative process came directly from his experience in the archive. Such awareness is one of the foundations of creative, flexible critical thinking.

Archives are our humanities labs, the material and digital sites where student-scholars from any discipline, like Asier and Sophia, can participate in and experiment with research processes using rare, ephemeral, and surprising primary sources. I’m never more thrilled as an instructor than when I get to talk with my students about the materials they’re studying in the archives. It’s a joy to be able to tell a first-year Computer Science student at Georgia Tech, for example, that their research on a small poetry press they’re studying in the archive is making a meaningful impact in a scholarly field they never imagined they’d participate in. Brittain Fellows continue to make archives and archival research a key part of their teaching. The Writing and Communication Program’s expansion of the Ivan Allen Digital Archive, a collection of digitized primary sources from the administration of Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., mayor of Atlanta from 1962-1970, co-curated by Dr. Amanda Madden and myself, is evidence of this ongoing commitment to archival pedagogy at Georgia Tech.

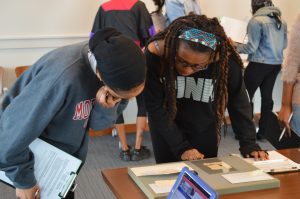

Emory students studying primary sources for a creative writing workshop at Emory’s Rose Library. Photograph by Nick Sturm.

These pedagogical opportunities wouldn’t be available without the help of the archivists at Georgia Tech and Emory who grow, preserve, and facilitate access to these collections. This article highlights archives as instructional environments through reflections by archivists at both institutions, offering instructors and archivists examples of how to work together on pedagogical collaborations with a range of purposes, scales, materials, and technologies. In the first section, Gabrielle Dudley, Instruction Archivist at Emory, describes a special collaboration between students at Spelman and the Rose Library. In the second section, three archivists from Georgia Tech collaborate to describe the innovative ways a technical institute functions at the intersection of traditional archival holdings and new technologies. Instructors who are interested in how allies like librarians and archivists approach teaching with primary sources will benefit from this article and might also find valuable resources from the Teaching With Primary Sources Collective, a branch of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Section within the American Library Association, and should subscribe to In the Loop, the Society of American Archivists’ free bi-weekly digital newsletter.

—Nick Sturm, 3rd Year Brittain Fellow at Georgia Tech and Visiting Faculty in Creative Writing at Emory University

Archives as Instructional Environments at Emory University

My role in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University is as Instruction Archivist, but informally I like to think of myself as a faculty coach and student advocate. Each semester I partner with faculty at Emory, and other institutions, to develop courses and research assignments that provide opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students to engage with primary source materials while learning critical archival research skills. In recent years our program has been expanded to better meet the needs of faculty and students through enhanced service. For example, we recently began the Faculty Teaching Fellowship Program which provides essential training for faculty seeking to teach with archives and special collections. The faculty attend monthly workshops and use the meeting time to develop a course from an idea into an innovative pedagogical plan that includes readings, discussions, and assignments that promote engagement with Rose Library collections. In recognition of stellar student scholarship, the Rose Library now offers three monetary award opportunities for undergraduate students. Students can earn the awards through scholarly research projects using Rose Library collections; these awards and targeted instruction have deepened the engagement of undergraduate students with the archives.

Gabrielle Dudley speaks to Emory creative writing students. Photograph by Nick Sturm.

As the Rose Library’s instruction services have been expanded to meet the needs of Emory faculty and students, we recognized the prospect of partnering with archivists, faculty, and students at other colleges and universities in the Atlanta area. The program had already been successful in working with faculty from area colleges including Georgia Tech, Morehouse College, Georgia State University, Agnes Scott College, and others, but we wondered how we could do this in a more intentional and impactful way.

In 2018, I received a grant to do a collaborative partnership with the Spelman College Archives to teach archives research skills to undergraduate students at Spelman and Emory using the papers of Black women writers. The grant was designed to create two experiences for the students: an archives exchange and an intellectual community. For the archives exchange, Spelman students enrolled in “The Art of Writing” course and the Emory Students enrolled in the courses “Black Women Writers” and “Reading Alice Walker.” And both visited the archives at Spelman and Rose Library. This institutional exchange allowed students to learn more about each institution’s holdings related to Black women writers and to orient them to the physical space, institutional environment, and archives research culture which included policies, procedures, and holdings. Working with undergraduate students I have come to realize that it is important to prepare them for the shift in cultural environment when doing archival research at a college campus that might be very different than their own.

In connection with their course assignment, each student was required to choose a Black woman writer (whose personal papers were held at Emory or Spelman) to study and conduct in-depth research on in the archives for several months. The list of writers to choose from at Spelman included Audre Lorde and Toni Cade Bambara and Rose Library offered the papers of Lucille Clifton, Pearl Cleage, Alice Walker, Mari Evans, and Natasha Trethewey. This project, alone, led to increased use of and interest in Black Women collections at Rose Library. Of the 30 students connected to this project, 20 chose to conduct research in Rose Library which translated to 72 research visits and 290 items circulated in the reading room. In addition, we received 37 reference questions via email and conducted 8 research consultations as a result of this project.

Spelman students at Rose Library. Photograph by Courtney Chartier.

After completing their research, 28 students involved in the project met for a one-day, symposium-style event and presented their research findings to one another. Though the presentations were scholarly in nature almost every student commented on their personal experience of shifting through the personal effects of famous authors. For example, one student chose to study award-winning playwright and Atlanta resident Pearl Cleage while she was also serving as a student production assistant for Cleage’s then-running plays Hospice and Pointing at the Moon. The student spoke about the surreal and slightly uncomfortable experience of working with Cleage on set while simultaneously reading through her personal correspondence, production notes, and play scripts in the archives. More than half of the students involved in the project identified as Black women and commented that it was “intriguing,” “empowering,” and “liberating” to conduct archives research projects solely on Black women writers. It was clear that while the projects had deep personal meaning for some students, others found it to be “exhausting” or “tiring” due to the extensive research they felt these Black women writers deserved and also recognizing that archives research is a time-consuming endeavor. Additionally, this project helped to make strides in establishing an intellectual community between the students at Spelman and Emory. During the symposium students were eager to share and learn from one another, though offering an opportunity for students to meet earlier in semester might have encouraged a stronger and more sustainable community of scholars.

Similar to the students at Spelman and Emory, this project had deep personal meaning for me as an archivist and avid reader of literature written by Black women. With this project my personal and professional worlds converged as I was able to share with faculty and undergraduate students the connections between Black women writers that I had found through an exploration of their photographs, journals, notebooks, and correspondences within the archives. I am especially encouraged by the words of Spelman student Tangela Mitchell, “I came to the realization that, without this project, it is likely I would never have stepped foot inside Rose Library. I feel indebted to this research project for everything it has brought me. It brought me Mari [Evans]…. It brought me a community of support and a second home at Emory.” This project is one of the highlights of my professional career, thus far, and represents the growth of the Rose Library’s instruction program and a model for how I would like to continue to engage with archivists, faculty, and students at Emory University and beyond.

—Gabrielle Dudley, Instruction Archivist at Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

Archives as Instructional Environments at Georgia Tech

Student-created posters inspired by rare books from the Georgia Tech Archives and Special Collections, created for English 1102, “Visual Culture, Digital Archives and H. Rider Haggard,” taught by Dr. Kate Holterhoff. Image courtesy of Georgia Tech Library Exhibits Manager Kirk Henderson.

Students at Georgia Tech live in a digital world, a forward-thinking environment that pushes them to always be “creating the next.” What is the value of archives in a “next”-focused campus? What is the intersection of archives and undergraduate instruction at a STEM-driven school? The relevance of non-current records in a future-oriented environment comes into focus when considering the skills required to critically approach research questions, find creative solutions, and develop innovative products. No matter the student’s major or interest, components of archival literacy, such as evaluating resources for authenticity and considering different points of view, carry relevance beyond the classroom. And using archives is a fun way to play with history! With this concept of play in mind, the Georgia Tech Archives and Special Collections developed the History Detective exercise where groups uncover the answers to questions on a given topic related to campus history. Designed to familiarize students with handling unique materials and sleuthing answers in pre-selected archival resources, this exercise has become one of the most popular offerings among faculty. The History Detective exercise also introduces students to the serendipity of information finding in the archives. Nonlinear research paths take more time and diligence than contemporary searching methodologies using online browsers and database search engines, but they also develop individual authority and opportunities for new knowledge creation. Working with course instructors, archivists take an active role in teaching critical thinking and research skills through hands-on learning exercises. Through interaction with the records, students may relate lessons taught in their classes to the real life experiences of the record creators.

Students visit the Archives to explore zoetropes and other artifacts from an optical toy collection curated by Dr. Patrick Ellis, which will inspire their own D.I.Y. optical toy creations. Image courtesy of Georgia Tech Library Exhibits Manager Kirk Henderson.

Archival instruction gives students valuable experience with physical historic materials, providing a lens to the future by looking through the past. Visits to Archives and Special Collections often involve a discussion on materiality, comparing the physical object to a digital surrogate. Students discuss the sensory elements of the physical: the fragility of the pages of a seventy-year-old science fiction magazine, the musty smell of the paper that suggests age, or the “magical aura” of the faded ink on a 17th century map. Through archival instruction, students make connections between what they have read and discussed in class to archival collections. A physics class reads about Sir Isaac Newton and Tycho Brahe, then sees in front of them the 1st edition of Newton’s Principia or an illustration of Brahe’s observatory in a 17th century atlas. Looking at an original book or manuscript puts the item in context so students can understand how the parts of the object relate to the whole, allowing them to experience the item as it was originally intended by its creator. They are able to weigh holistically the pros and cons of different formats; gain additional perspectives into campus history; the origins of science and technology; and popular culture, while developing a better understanding of the value of archives. Archival instruction also opens the door for creating links between the past and present through projects like physical and digital exhibits, podcasts, and media archaeology. Archival instruction enters a new realm of possibilities with the incorporation of technology innovations like augmented and virtual realities. A pilot class at the Georgia Tech Library invited students to design creative solutions for engaging the campus community with items from the archival collections. Through these types of educational programming efforts archivists can take an active role in student research.

“Cooking Mama: Food Fight” game created by student for CS2261 Media Device Architecture, playable on original Game Boy Advance device.

Perhaps nothing underscores how rapidly “the next” becomes “the past” for our students than the vintage computers, consoles, and other technologies we make available for teaching and learning in our retroTECH Lab. retroTECH’s mission is to inspire a culture of long-term thinking and ongoing access to technological heritage. Through retroTECH’s activities and lab space, students engage in experiential learning related to how our lives shape technology—and how technology shapes our lives—over time. Video game history and artifacts, in particular, resonate deeply with our student body and provide rich opportunities for course-integrated instruction related to user experience and narrative in digital spaces. As part of several computer science and digital media courses at Georgia Tech, hundreds of students each semester build programs for the Game Boy Advance. We have recently begun an initiative to collect these student games, alongside audio interviews with the student creators. During visits to the lab, students can compare the experience of playing the games on the original Game Boy Advance hardware as well as in a browser-based emulation environment, inspiring reflection on themes of materiality and authenticity. These interactions also offer an opportunity for us to talk with students about the histories they are making in the now and about how they view their own personal archives—the games, essays, or photos they create and have the power to share, preserve, or even delete according to their own archival decision-making. From watching the expressions of wonder on students’ faces as they use a typewriter for the first time or rediscover the flip phone their parents used when they were in kindergarten, we witness how technological artifacts can be instigators of multigenerational connection and empathy.

—Wendy Hagenmaier, Digital Collections Archivist; Amanda Pellerin, Access Archivist; and Alison Reynolds, Special Collections Archivist at Archives and Special Collections at the Georgia Institute of Technology