It’s grading season, but at Technically Pop, we are already dreaming of winter break. Join us as we explore holiday content from Charles Dickens to Mariah Carey. Alexandra Edwards ponders the role of Phil Spector, convicted murderer, in shaping the sounds of Christmas; Josh Cohen reads of Love, Actually as a post-9/11 movie; I argue that The Muppet Christmas Carol is the best Dickens adaptation; and Molly Slavin explains how the McCallisters afford that giant house.

Recommended Reading

“Mariah Carey Rereleases ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’ Video with Unreleased Footage”; “Phil Spector’s ‘A Christmas Gift for You’–The Shocking Story of the Ultimate Festive Album”; “Phil Spector’s A Christmas Gift for You Aimed at Respectability–and Created a New Tradition”; “I Rewatched Love Actually and am Here to Ruin it All for You”; “Love Actually is the Least Romantic Film of All Time”; Christmas: A Biography; Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol

Fact Checks

Although it was never officially released, a collection of Christmas songs recorded by Arcade Fire leaked onto the internet in 2012.

Kacey Musgraves’s Christmas special, The Kacey Musgraves Christmas Show, is streaming on Amazon Prime, not Netflix.

Music credit: “Amazing Plan” by Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com)

Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Edited by Corey Goergen

Transcript by Alexandra Edwards

Transcript

Josh: Hi, this is Josh Cohen.

Alexandra: This is Alexandra Edwards.

Corey: This is Corey Goergen.

Molly: This is Molly Slavin, and we are Technically Pop.

[Theme Music]

Corey: Okay. So we’re here today at the end of your fall semester with a holiday evergreen extravaganza. Through the magic of editing underneath my voice will hopefully be a fair use amount of Mariah Carey’s massive hit “All I Want for Christmas is You”, which we are celebrating its 25th anniversary this year. Mariah Carey is especially celebrating this with the tour, a rerelease of the album that it appears on, new merchandise, including hoodies and things, a co-licensing deal with Walkers Crisps, not Lay’s potato chips, but Walkers Crisps.

[Mariah Carey singing “All I Want for Christmas is You”]

Corey: It seems like she’s pushing to get this thing to number one on the Billboard charts, which has never happened before. The last couple of years, it’s been charting in the top 10 again, and as of last week, I just checked, it’s at 39. So it’s well on its way. And this is, we’re recording this before Thanksgiving. So even before Thanksgiving, this is already a hot top 40 hit. Carey gave an interview about this. She made some jokes about how she was an infant 25 Christmases ago, and she says that she lives “in the land of the Tooth Fairy and Santa Claus. I don’t acknowledge time. I don’t know what it is. I rebuke it.”

Alexandra: You know, I like that. I like that. I like Mariah Carey’s take on things usually. But also, if she rebukes time, how does she know that it’s Christmas?

Molly: It’s a great question.

Corey: I think she rebukes linear time.

Alexandra: Ah, but not cyclical time.

Corey: Which is what we’re gonna do today with our evergreen spectacular. We’re going to come right back and talk about Mariah Carey and other great musicians who have made great Christmas music.

Alexandra: Great in air quotes, possibly.

Molly: No, just great.

Corey: Great in many senses.

Alexandra: Okay.

[Ramblin’ Wreck horn]

Alexandra: Yeah, what does make “All I Want for Christmas is You” a classic holiday song?

Molly: I would like to early submit that I don’t think it’s just a holiday song. It is played year round at my favorite bar in South Bend, Indiana with no regard to the season.

Alexandra: They also, they rebuke all kinds of time.

Josh: Daylight savings…

Molly: Actually, Indiana did rebuke daylight savings until I think I was 20 years old.

Josh: To be fair in South Bend you do a lot of yearning for Christmas much like other parts of the Midwest, so I doubt it’s quite as often in San Diego for instance.

Molly: I don’t know, I’m really thinking… I am going to make a case that I think this song really translates both linearly and cyclically. I think it is a great Christmas song but I also think it’s just a banger.

Alexandra: See, this is interesting because I do feel this way about Joni Mitchell’s “River” but I don’t feel this way about “All I Want for Christmas is You” that is, it literally says Christmas in the title. It is a Christmas track.

Corey: Yeah, the bells and the various Christmas music accoutrement run through “All I Want for Christmas is You” whereas Joni Mitchell, you just get that little “Jingle Bells” riff, right. And she mentions Christmas. But then…

Molly: I’m not debating it’s marketed as a Christmas song or that there are Christmas tropes in it. What I am saying is that it works well as just a happy song, a happy little pop jingle for all the seasons of the year.

Corey: I think it’s a good enough Christmas song that I would not be upset about hearing it in March, or any other month.

Is this just one bar? Or is this throughout South Bend?

Molly: Correct. It is one bar in South Bend.

Corey: Is it like the Mariah Carey themed bar?

Molly: No, it is just a bar. The first time I took John to this bar, I forgot to warn him and I think it was after a football game. Certainly. So it was in the fall, but not close enough to Christmas for it to be excusable. And the song came on and John was like “What is happening?” But I truly think, I truly think that it is. You would be happy to hear it in March.

Alexandra: Now are there other songs at this bar that play repeatedly throughout the year at times you might not expect them or does this bar just have a particular affinity? I need to unpack this.

Corey: This is inside baseball: this is not on the schedule for our episode but I…

Molly: Full disclosure, I forgot about it until about 10 seconds ago.

Alexandra: Molly, I feel like you always bring a bombshell to drop into these episodes.

Molly: I’m very sorry, I one hundred percent forgot about this until we started recording.

Corey: No: This is very good content. Say more.

Molly: There are, so this bar certainly has standbys, like it plays a lot of Springsteen. It’s like that kind of bar. But this is the only thematic song.

Alexandra: Is there a crossover between the audience for Mariah Carey’s Christmas bangers and Springsteen?

Molly: Yes. And it can be found at the Linebacker Lounge in South Bend, Indiana.

Corey: I am upset that you’ve held out that it’s called the Linebacker Lounge until now. So does the clientele of the Linebacker Lounge react when it comes on?

Molly: Everyone freaks out.

Corey: Do they? Do they–

Molly: Everyone does every word.

Corey: We all sing along?

Molly: Yes.

Corey: Okay.

Alexandra: This is like the Journey of South Bend, Indiana.

Josh: The “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

Molly: It is the “Don’t Stop Believin'” of South Bend.

Corey: I will sign the petition to replace “Don’t Stop Believin'” with “All I Want for Christmas is You”. You’ve won me over.

Molly: Because it’s not a Christmas song, it is a year round banger.

Alexandra: I guess you could think about what you want for Christmas at any point during the year. It doesn’t have to be the Christmas season to think about what you want for Christmas.

Molly: You sure can.

Alexandra: All right. I’m convinced.

Corey: I’m convinced by the claim. Is the further part of your claim that that’s what makes it a good Christmas song? That a good Christmas song has to also be not a Christmas song?

Molly: I’m not willing to make that blanket claim. I am willing to make it about “All I Want for Christmas Is You.”

Josh: I will make that blanket claim. If you can’t even consider listening to it and it’s not Christmas then it’s just so yoked to Christmas clichés that I don’t think it’s actually that good of even a Christmas song.

Alexandra: Okay, okay, I was gonna say I will concede that a song like “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)” which is my favorite, like in my top three favorite Christmas songs, is also a song that I would react like the patrons of this bar were I to hear it at any point during the year, I would yelp and start singing every word. Loudly.

Corey: I would be there with you. Less in key than you I am sure.

Alexandra: I don’t know.

Corey: Oh, no, I do know. So okay, so we have Darlene Love, “Christmas (Baby, Please Come Home)” and Mariah Carey, “All I Want for Christmas is You.” These are our starting points in this canon. What about these two songs? What do they have in common that make them not annoying in February or April or October?

Alexandra: They just slap. I think both of them just slap.

Molly: To quote Tom Haverford: “It’s a banger. A certified banger. How dope are the drops?”

Corey: So there’s something sonic about these songs that works?

Alexandra: I agree. Yeah.

Corey: Okay.

Alexandra: Yeah. Which is also how I feel about The Pogues’ “Fairytale of New York.” Which is another Christmas song that I would happily hear at any time of year.

Molly: I would agree with that.

Corey: I think that’s less of a Christmas song than the other songs that we were talking about.

Alexandra: The bells are ringing out for Christmas Day.

Corey: Okay, but it’s–

Alexandra: It’s Christmas Eve and he’s in the drunk tank, like, it is yoked to the season.

Corey: But no more so than these other songs that we’re talking about. And it’s, it’s a fairy tale of New York.

Alexandra: It is, you’re right. It’s not a fairytale of Christmas.

Corey: This is an immigrant story. This is the Pogues, right, this is sort of this imagined immigrant tale right? It happens to be at Christmas time. It is a Christmas song in the way that Die Hard is a Christmas movie.

Alexandra: The best Christmas movie.

Josh: It is the best Christmas movie. Followed by Mean Girls.

Alexandra: I missed the Mean Girls train, so. That’s not my, it’s not an appraisal of the film, I just missed it.

Molly: But Mean Girls follows an entire academic year, there’s just a portion of it at Christmas.

Corey: It crosses through Christmas.

Alexandra: Which is a lot like You’ve Got Mail, is another seasonal… I don’t want to recuperate You’ve Got Mail. Strike that from the list.

Corey: But this also raises the same genre question, right? Goodfellas also has a moment that is in Christmas. It actually features Darlene Love’s song in it, very briefly. Okay, so the sonics of the songs make them last. These are also all story songs or character driven songs to a certain extent, right? They aren’t, as Josh pointed out, they’re not just wrapped up in Christmas cliches, there’s a relationship at the center of all three of these songs. I also think, and I’m going to set the Pogues aside for just a second. I want to put Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You” in the same lineage as Darlene Love’s “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)”. Mariah Carey is very much singing in that sort of 90s r&b style, but there are these, the bells, the horns, the fact that it slaps in a very similar way. There are these sort of elements of Phil Spector, right, in this song. I think this song doesn’t exist without Darlene Love coming before. The call and response vocals that come in I think in the second verse, chorus moment. Yeah, and I think in some ways like Phil Spector shapes how–well you and I, I know, because Alex and I talked about it. Phil Spector shapes how we think about Christmas music.

Alexandra: Oh, absolutely. Completely, completely. Yeah. And there’s an interesting thing where people are saying now as Mariah Carey is trying to get her song to chart again, that they’re saying like, “Oh, I didn’t know you wrote this, like, I thought that this was a cover of some traditional, like, 60s Christmas song.” And she’s very flattered by that. And I feel like I was yesterday years old when I realized that, in fact, she did write it in the 90s. Right, but it so much plays into that tradition of A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector, which is the name of the album that we’re thinking about. It plays into that so much that it seems like it could have been on that album originally.

Corey: Yes.

Alexandra: Which is a very interesting album, just in general.

Corey: What’s interesting about it?

Alexandra: I mean, apparently that, though it is stacked beginning to end with bangers–certified bangers– apparently the recording process was terrible and Phil Spector, I mean, as we know is a garbage person. Convicted murderer.

Corey: Yes, absolutely killed a person and was convicted for it.

Alexandra: Absolutely did a murder, got caught, and is in prison for that murder. But also apparently he was torturous to the point of being, like, outright abusive to his artists as they were recording this album, which makes it a real moral landmine. You listen to it and think about these people suffering, just to get this beautiful wall of sound sort of thing.

Corey: Yes. So this is this is early 60s Phil Spector, so far enough into his career that he sort of has a style. He has this sort of collection of artists that are working with him, that are associated with him. And this is sort of his like, flex record, right? “It’s sort of these are all of the talented people I have working for me. This is the impressive sort of production things that I can do.” And it is released in 1963, on the day that John F Kennedy was assassinated, which a lot of people have said kind of hampered its reception. Right. So, Noel Murray, in an article for the AV Club a few weeks ago–a few years ago, excuse me–writes about this. And, right, we think about this day, the assassination of JFK, as sort of the start of the 60s in many ways, or the sort of split, right. There’s that famous scene in, or that episode of Mad Men, with the Kennedy assassination, things like that. And Murray points out that, in 1963, when this album comes out, Spector is kind of the new kid on the block. And he’s sort of not respectable. He has the long hair and he’s coming into this space, Christmas music, that until this point had been respectable. So like very old, old school sort of like show biz–

Josh: It’s Bing Crosby–

Corey: Bing Crosby, right, big band, like, the closest thing to a rock and roll Christmas song is Brenda Lee doing “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” or something like that. And there were a lot of raised eyebrows at Spector even before you have this national tragedy. The album doesn’t really come back to prominence until 1972 when Apple Records reissues it. So Apple Records is the record label founded by The Beatles. Spector, by the end of the 60s, is working with the Beatles quite often. He famously produced “Let It Be,” or made something out of the “Let It Be” sessions to release on the Beatles last album. By ’72 the Beatles are gone. The 60s are over. And we get this album rerelease. And it must have sounded old then. It no longer sounded new. And I can’t… I feel like, and this is also the strength of Mariah Carey’s song, is that we want nostalgia in these songs, right?

Alexandra: Yeah.

Corey: We don’t–It’s hard for a song to become–

Josh: You don’t want an innovative Christmas track.

Corey: Yes.

Josh: You don’t want it to be cutting edge, right? The form has to follow the message of “Yes, Christmas is traditional, it’s nostalgic.”

Alexandra: It has to seem like it has played on the radio every Christmas for 10 or more years. I would say 10 years is it’s probably even too short. Which wilds me out about, like 1972, this comes back and comes to prominence. Right? Because that’s not long enough, you wouldn’t think, to activate nostalgia yet. But maybe so much had changed.

Molly: Yeah. If we accept that the 60s started with the assassination of JFK, I think definitely–

Josh: Those were solidly top 10 worst nine years in terms of American turbulence.

Molly: To be matched only by what’s to come.

Corey: Yeah, and pop music is transformed, in large part in Phil Spector’s image. Without Phil Spector you don’t get Brian Wilson. Without Brian Wilson, you don’t get Sgt Pepper’s. And we are four years away from “Born to Run,” right, which is Bruce Springsteen just like striving after Phil Spector. I mean, it’s old fashioned by that point, even though it’s barely a decade.

Alexandra: It’s interesting to me, then, that when we did, in the 2000s, the Phil Spector-Bruce Springsteen revival, like indie band revival, with the Arcade Fire and everything, it’s fascinating to me that we did not get a new Christmas classic track out of that. Unless we did and I just don’t know it.

Corey: Did the Arcade Fire release any Christmas music?

Alexandra: I don’t think they ever did. Maybe it was just that indie artists were not interested in doing that sort of… they weren’t trying to chart at the holidays or something like that.

Corey: Yeah, I mean, Sufjan Stevens was very interested in Christmas music, and has released five hours Christmas music.

Josh: But it’s not exactly radio friendly,

Corey: But most of it is not radio friendly, yeah.

Josh: I mean, it’s good.

Corey: Much of it is very good.

Josh: Excellent.

Corey: Yeah, some of it is unlistenable. But much of it is very good.

Josh: As with all Sufjan, there’s a quota there. Yeah.

Alexandra: This makes me wonder then if, you know, eight or nine years from now–I mean, arguably now is also a very turbulent time in American history–if, for example, One Direction’s like Christmas-adjacent song will be our holiday classic.

Molly: Oh, if there’s a buck to be made, they’ll release it. You know?

Corey: The person who’s trying hardest right now is Kacey Musgraves, who released a Christmas album maybe three years ago? Before The Golden Hour, which is her big album that just won the Grammy for Album of the Year. But now she’s releasing a Netflix, one of those old school Christmas specials.

Alexandra: I’m in, I’m in. Kacey Musgraves is like lesbian-adjacent right? The queers love her for some reason. I am on board for it. I am a queer. So I don’t mean that as a slur, I feel like I have to clarify to our audience.

Corey: Yes, yeah, I think she’s, her fan base is an interesting Venn diagram. She’s sort of coming out of country but in sort of a progressive tradition. She was initially in the sort of Loretta Lynn kind of space and is now doing like a 70s, Dolly Parton disco country kind of thing.

Alexandra: I’m for it.

Corey: But yeah, so the special is coming out. She just unveiled a new Christmas song that I think wasn’t on that album, like last week. She’s clearly gunning for this. But it’s hard to predict. In our planning for this, I asked people for predictions, and there are none because I don’t think you can know until it’s happened. I don’t know when I realized that “All I Want for Christmas is You” will always be with us. Right? Like it was just all of a sudden “Oh, yeah, that’s now canon.”

Molly: I mean, if “All I want for Christmas is you” is now canon, I think there’s a strong argument to be made that it’s the film Love, Actually that catapulted it to canon status.

Corey: I think that’s right. I think that’s part of it. And I think, it’s a similar nine- or ten-year window, right? Because Love, Actually is 2003. ’94, so yeah, this song is about a decade old. And all of a sudden this movie comes out, and… We’re going to take a break, and when we come back, Molly is going to defend this movie from the internet haters.

[Ramblin’ Wreck horn]

Corey: So we’re back. And–

Alexandra: Okay, so what’s interesting to me, though, is that this nine year window seems to be what makes a Christmas classic. But we are well past the nine year window from the time that Love, Actually came out. And if you look on the internet, people hate this film, hate it with a passion. I think there are roughly 20 or 25 takedowns of this movie that have come out in the past few years. So I’m interested to know: why do we have such ire about this movie? And can it be recuperated?

Molly: Yes, one–So I think, yes, it can be recuperated, just be clear. I don’t think it was clear what I was answering. I also think the reason a lot of people our age have ire about this movie is because it was released in 2003, which was late high school for me. But I really got into it in college, which is when I think for a lot of you, it was released. And so I think it’s released or we become conscious of it at a time when we’re sort of developing a political consciousness, when we’re developing sort of ways of understanding culture that are different from what we had before. And I think this is a convenient excuse to get mad online, frankly.

Alexandra: So it’s just all about the clicks.

Molly: No, it’s not all about the clicks. I phrased that poorly. It’s a way to express a lot of the academic theories we were learning and I would like to say up front, this movie does have a lot of problems and I’m not here to defend it from all–

Josh: It’s not Casablanca.

Molly: Yeah. It’s not–it’s not got a great queer representation to put it mildly. Race is not dealt with very well at all. It’s not the most feminist movie I’ve ever seen. But I do think it gets more flack than it deserves.

Alexandra: Okay, so what is some of the criticism that people lob at this film?

Molly: Well, Alex, nice, you have pointed that out. I have printed off what I think is sort of the most canonical takedown of Love, Actually, which is Lindy West’s piece in Jezebel about titled “I rewatched Love, Actually, and I’m here to ruin it for all of you.” It was published in December of 2013. And I feel like for some reason this has become the classic. It maybe was one of the earliest, maybe it’s one of the longest, I don’t know.

Josh: She really distills the ire that a lot of people feel in a–

Corey: It’s comprehensive.

Josh: Rant worthy– or, yes, a thorough comprehensive rant.

Molly: Yes. And I have a lot of critiques of this. The one I want to start with, though, is perhaps one of the ones I feel the most strongly about, that is one of the weirder plot lines and that I think a lot of people do have issue with, in some ways that I think are justifiable and in some ways I don’t. Where she starts writing about the Colin Firth storyline. So I’m just going to read a few paragraphs of what Lindy West says, and then we can break it down a little bit. “Colin Firth’s girlfriend is sick. NBD, right!? WRONG. Turns out, she isn’t sick with the flu—she’s sick with ColinFirth’sBrother’sDongitis!” As a reminder, if you haven’t seen the movie in a while, one of the earliest plot lines is Colin Firth’s girlfriend is sleeping with his brother. “Colin Firth cannot deal, so he runs off to France all sulky to fucking type a novel on a fucking typewriter in a mansion.” It is not a mansion, it is a lakefront cottage. “Siiiigh! ‘Alone ah-GAYN!'” That was my British accent which I will not be pulling out anymore throughout this episode. “This old French woman shows up at Chateau de Firth and is like, ‘Here, I found you a lady. I’m literally giving you this lady.’ Score! Free lady! The lady is named Aurelia and she only speaks Portuguese, and so does her entire family, apparently, even though all of them live in France. It’s irritating. Colin Firth falls in ‘love’”–and love is in quotes–“with Aurelia at first sight, establishing Love, Actually’s central moral lesson: The less a woman talks, the more lovable she is.” Okay. So what Lindy West portrays as this old French woman showing up and saying “here, I found you a lady. I’m literally giving you this lady” is not actually what’s happening. This is Colin Firth’s, either he owns the home or it’s a timeshare or something. He’s an established figure at this home. And he seems to hire a cleaning service whenever he is there, run by this woman and this woman says this is a new woman we have hired. This is the woman who will be cleaning.

Josh: Yeah, she’s the maid.

Molly: She’s the maid. It’s not “free lady,” right? Like, this is a established maid service he has contracted with in the past, who, he is paying for her labor.

Alexandra: Okay. But to be fair, though, we have to acknowledge that there is some weird, like, slippage between the kinds of domestic labor that maids do and the kinds of sex labor that sex workers do, and that there is an established tradition of maids being at risk of being taken as sex workers–

Molly: Absolutely.

Alexandra: –in these spaces because they’re in these intimate domestic spaces. I don’t think Lindy West is that far off here in reading these things as being imbricated, to use a big grad school word.

Molly: Certainly there is that a little bit, but this is not–so Lindy West goes on to talk about–Well, I’m getting a little ahead of myself–about this being a sex trafficking storyline, which I 1,000% disagree with. And I definitely agree with you that there is that slippage but I’m saying the “here I found you a lady, I’m literally giving you this lady” is not accurate. She’s being paid for her labors. He drives her home at the end of the day. There’s no gifting happening here. This is not like a medieval vassalage or whatever the word would be. I don’t think that’s the right word. I just want to say I don’t think I got that right.

Corey: It’s the holiday episode. It’s close enough to the right word.

Molly: Then Lindy West goes on to say that Love, Actually’s central moral lesson is “the less a woman talks, the more lovable she is.” Aurelia actually talks a lot. She actually never shuts up. It’s just in Portuguese, and Colin Firth can’t understand her. But that doesn’t mean she’s not talking. It just means Colin Firth is too dumb to speak the language that she speaks.

Josh: Though dedicated enough that he will eventually learn Portuguese.

Molly: Correct.

Alexandra: Badly.

Josh: But humorously for the audience.

Corey: …and he speaks it to her father first, not her.

Josh: He does. His command of idioms is limited.

Alexandra: It’s also the reason that Aurelia’s sister genuinely believes that her father is selling her as a sex slave to a British man.

Molly: So the Portuguese community that is in Marseille is one of the things I’m actually willing to, like, cede. That is weird. What is this Portuguese community doing in Marseille? I don’t understand that. Unless it’s some sort of pro-EU fantasy, like pre-Brexit.

Alexandra: Is it like a port city thing?

Molly: It is a port city.

Alexandra: They got on the ocean and just ended up in Marseille.

Molly: But that makes it too convoluted. Why not just have him go to Portugal?

Alexandra: Colin Firth.

Molly: Yeah.

Alexandra: Well, we have talked about this and I think that, it’s not foreign enough, like part of the whole storyline is that they’re both foreigners in this place, right? And then she, when she’s in his home does not have her community with her. And that doesn’t work if she’s just in her native land, where she speaks the language and she is like, just acclimatized to be there and it’s all very normal.

Molly: But what is weird about it is she does seem to have lived in Marseille long time. There’s this huge Portuguese community–

Alexandra: You’re right. You’re not wrong.

Molly: But the other thing I return to is the Portuguese community is very weird. Like there’s the whole, “Father is going to sell Aurelia to this English man.” It’s like a game of telephone where things are getting translated down the line. And at one point, a little kid yells, “he’s going to kill Aurelia.” And everyone else is like, “cool.” Like, what is going on with this dysfunctional Portuguese community? I will admit is a sticking point.

Alexandra: But it is also a very sort of racialized comedy, where British people do things alone and they’re relatively– even if they’re silly, they’re still relatively refined. But Portuguese people are just screaming things out to each other and the whole community has to be involved in everyone’s business. And like, it’s a whole communal sort of weird thing. You can’t just marry one of them, you end up marrying the whole community. There’s something I don’t quite care for there.

Corey: But it’s not quite coherent because the movie is all about these connections between these British people. But it’s not depicted in the same comedic way as this village that marches to the restaurant, right?

Alexandra: Except when it’s Hugh Grant as prime minister because he is prime minister of the whole country. And therefore they do all sort of become this community when he’s looking for Natalie. I don’t like what this movie does in terms of fat shaming.

Molly: I don’t either.

Corey: It’s very bad.

Alexandra: It fat shames at every single turn. Yeah, and the storyline that actually seems to me to be the truly the most about sex trafficking is the kid who goes to America and then brings home two dumb American women.

Molly: That storyline is indefensible.

Josh: “Colin, god of sex”?

Alexandra: Yes.

Corey: Yes. And goes to Wisconsin and comes back with two women with bad Texas accents.

Molly: The bar in Milwaukee has Bud Light signs which it would never have. Milwaukee’s a Miller Lite town. The whole storyline is indecipherable.

Josh: The thing is that–the movie does to America and the Portuguese community in Marseille the same thing. It just takes one characteristic. So Billy Bob Thornton plays the American president. He’s very sleazy.

Molly: He’s George Bush.

Josh: And… Well, he’s a sleaze. He’s pretty sleazy.

Corey: He’s Clinton-Bush mashed up.

Molly: Yeah, you’re right.

Josh: In 2003, this reads like, “man, Richard Curtis, director of the movie, is being an unfair, you know, British perspective on our president.” Things look a lot different now in 2019, which we don’t have to get into, but. Billy Bob plays this sleazy guy who sexually harasses Natalie, who is Hugh Grant’s–the prime minister of the UK–is working on the staff there. Then you get these women in this bar in Milwaukee who are just so taken with Collin that they have a foursome with him immediately upon meeting him because he speaks in the British accent. You get the same–basically it’s just, Americans like sex and they especially like sex with British people. That’s it. That’s the depth of being an American in this movie. The same thing with the Portuguese people: “Oh, they are rowdy and rambunctious and they do everything communally. And maybe they’re not that smart, but they’re warm and passionate.” And I would argue the problem with the movie is that it does the same thing with all the characters. Colin Firth plays the guy who uses a typewriter. That’s it. There’s no elaboration of who he is as a person. Liam Neeson plays a stepdad who is trying to give his son advice on his crush. That’s it. There’s nothing else.

Alexandra: Well, he’s sad.

Josh: Is he? He’s just kind of there. I mean, sure. His wife is passed away, he’s sad.

Molly: No, he breaks down and Emma Thompson comforts him at the kitchen table.

Josh: Well, this is before Liam Neeson learned to show emotion, like in Silence. So that scene is–It’s bad. It’s bad. But my point is all of the characters with the exception of Emma Thompson, who is a delight in everything and is the MVP of this movie, all of the characters just have one single trait, because there’s 27 characters. Kiera Knightley, her character is that she’s a newlywed. That’s who she is. You know, none of these characters have any depth to them.

Corey: She’s a newlywed, to be fair, who likes to look at her own face.

Josh: She is–

Molly: No she’s creeped out by her own face, because–

Corey: No, she’s not, she’s charmed.

Molly: Oh, you’re right. She is.

Corey: It is creepy. We are creeped out by this as observers of the movie.

Alexandra: I actually think that that is the most indefensible storyline, the Keira Knightley storyline, not Colin in America. Because if those four American girls want to have sex with him then that is fine and I am not going to kink shame that. If you want to have group sex, have fucking at it. But that Keira Knightley storyline, in which Andrew Lincoln shows up and is like, “hey, by the way, I’m going to dump this on you, this emotion, I’m going to force you to do this emotional labor to deal with the fact that I’m in love with you.”

Molly: You’re right.

Corey: She is charmed by the fact that–

Molly: No, he’s very reticent to confess that. It only comes out because she shows up and like insists they watch this tape which he doesn’t want to do.

Corey: But when he comes over later, in what is now, like, is depicted as the most romantic moment in the movie, but it’s actually this–Yeah, like, sure she comes and watches the footage, and he could just leave it. But instead he goes and makes her lie to her new husband,

Molly: Right, okay.

Josh: His best friend.

Corey: And his best friend, to justify the fact that he just apparently hasn’t talked to her for years. Right? Like, that’s the other part of this plot is that she thinks he hates her. Because he won’t speak to her, because… he loves her?

Josh: It’s some weird like sublimated desire kind of thing. Yeah, where he has basically been standoffish their entire relationship. He has then spent their wedding videotaping extreme close ups of her

Alexandra: Her teeth, specifically.

Josh: Mostly her teeth. Well, it’s Kiera Knightley so that’s most of her face. And he makes little to no effort to prevent her from watching this, you know, he’s like, “I don’t know where the video even is.” And she’s like, “Oh, it’s right here. It’s labeled.” And he’s like, “I guess it is” and then, you know… Any rational person would tear up the VHS–which, it is a VHS–turn off the TV, make some excuse. There’s this kind of thing where he wants this to be drawn out as much as it pains him. And then there’s this later scene where he pretends to be carolers. He brings a boombox. He plays a track of “Silent Night” so that, then he shows her a bunch of cards where he’s written out this message confessing his love but basically being like, “I know this isn’t going anywhere.” He walks away, she gives him one kiss on the lips, and he’s then like “oh, that’s all I need now.”

Alexandra: Nailed it.

Josh: Yeah, now I’m a whole human being again. I don’t know what to make of that.

Alexandra: Well it’s absurd, because in effect he’s forcing her to make a choice. You do not give someone that information unless what you want them to do is to actually have to choose between you or your–you know, the person’s new husband, who is again your best friend. So what he’s done is dumped the responsibility onto Keira Knightley to make some kind of choice between the two of them as though they’re equivalent. They’re not. She just married the dude, right? Like she just married him. Chiwetel Ejiofor, by the way, who is not–they do not do enough with him in this film.

Molly: He has like three lines.

Alexandra: It is a shocking underuse of an actor. I’m horrified by it.

Corey: It retroactively ruins what could have been like one of the actual romantic moments in the movie, which is that this best man has orchestrated this surprise rendition of “All You Need is Love” as they leave the wedding. And it’s like this elaborately filmed, staged thing where there’s suddenly new musicians popping up and Lindy West rightly points out that this makes no sense. Like, you can’t hide a brass section in a wedding crowd. But nonetheless, it’s like–

Molly: It’s also a weirdly small wedding.

Corey: It’s a very small wedding, but it’s this nice moment. It was inspired by Jim Henson’s funeral, which, something similar happened. But–

Josh: It’s pretty cool. It’s a pretty good scene.

Corey: It’s a pretty cool scene. But then the way the plot goes, it retroactively is ruined by his actual motivation.

Alexandra: His selfishness.

Corey: Yeah, right. This wasn’t–so the thesis of the movie is that love is everywhere, but the only–“love actually is all around us,” I think is what they say, quoting that awful song, which we should get to. But the only love that the movie makes space for is heterosexual love.

Molly: Disagree completely. I don’t think it makes space for–it makes space for friendship love between Bill Nighy and his manager. He leaves the fancy Elton John party to come hang out with Joe.

Alexandra: You’re right.

Molly: I think it makes space for familial love. I think there’s a reparative reading of the Laura Linney storyline.

Corey: I do not. I strongly disagree, but go on.

Molly: Another friendship love is between Emma Thompson and Liam Neeson, who I think Lindy West says like… I’m gonna try to find the quote.

Josh: What is their–Are they friends?

Molly: Yeah. So Lindy West writes, “The grief-stricken Liam Neeson calls up Emma Thompson, who I guess is just some woman he knows (relationship NEVER EXPLAINED).” First of all, it is explained. She says something about “back in college,” indicating they are college friends. Also, men and women can just be friends. You don’t have to explain the relationship there. They seem to be very good friends. There’s the Liam Neeson-stepson love relationship. I do think it–it doesn’t make space for queer love, certainly, but I do think it makes space for forms of love that aren’t explicitly romantic or heterosexual.

Alexandra: You don’t know if those American girls were in some sort of polyamorous situation with each other. They may have had a lot of love.

Molly: I will give you that.

Josh: They don’t have any blankets, so, yeah, I mean…

Molly: You know what, I opened by saying I thought that storyline was indefensible, but maybe this is the silver lining.

Corey: I like the defense. I think those relationships in the film are all in–wind up ultimately being in the service of the romantic relationships between men and women. So the Liam Neeson relationship with his stepson is very sweet. Those actors, I think, other than when Liam Neeson is trying to express sadness, there is like a lived-in quality to their relationship. But their scenes are always driven towards this grand romantic gesture that the son wants to make. Right? Emma Thompson and Liam Neeson–like there are these moments that hint at something larger, but it’s always on the peripherals of their other stories.

Josh: And the problem is, the movie is too driven by male fantasy. So I think that infects things that otherwise are actually potentially–have the potential to be a better story. So for instance, early on in the movie, Liam Neeson’s character makes this joke about Claudia Schiffer at his wife’s funeral. And then it recurs later, where the stepson asks him about his dating life and he makes this joke Well, maybe if Claudia Schiffer’s available. And then lo and behold, late in the movie, Claudia Schiffer plays the mother of one of the stepson’s schoolmates, and they have this brief exchange where it’s like, “connection at first sight, love actually is everywhere. We’ll come back to this later, you know, I’ll make sure that we hang out again.” And the way that it maps this materialization of this fantasy like, “oh, Claudia Schiffer” and then she appears in the movie, is exactly what the movie does with all of the male characters. And it’s the thing that brings the movie down essentially, there’s very–Emma Thompson is the only female character who has any kind of inner life. And of course, that’s only because her husband, played by Alan Rickman, is considering, mulling, contemplating cheating on her with his, you know, very brazen, forward assistant. So even that: her inner life is about kind of anguish and you know, being worried about her husband or family, which is a start. I guess you could say the same thing about Laura Linney’s character. So the two of them they have this conflict between devotion to family or pursuing their own happiness, but other than that everything is just like a male fantasy that then gets materialized at some point later in the movie.

Corey: I think the difference between Laura Linney’s plot and Emma Thompson’s plot is that the joy of–so Emma Thompson, right, the love that is not romantic is for her children. So there are these great moments after she has revealed to her husband, who is played by Alan Rickman, that she knows what has happened, where like you see her face turn. As she goes from being upset about this to being pleased to interact with their children

Josh: After they performed in the school nativity–

Corey: Yes. And then–before they perform, right, because the plot revolves around–She knows that Alan Rickman has bought this expensive piece of jewelry. She assumes it’s for her but she instead on Christmas Eve–

Alexandra: Question mark?

Corey: Or the day of the Christmas concert that her children are in, they’re all opening one present and she opens up what she thinks is this necklace but is instead a Joni Mitchell CD, which Lindy West rightly points out, one of the things we know about her is that she likes Joni Mitchell. And so she has this CD already. So he has bought her a cd that she already owns.

Molly: She’s, she’s absolutely right about that.

Corey: And this is when she realizes that there is this something going…

Josh: Someone else got that necklace.

Corey: And she steps away from the family and she takes the Joni Mitchell CD into a room and she’s listening to–and it’s that rerecorded version of “Both Sides Now” that Joni Mitchell released right around that time, I think. And it’s just a stunningly beautiful song and she is doing this great performance. And then she, like, puts back on this enthusiastic face to get them to the concert. Laura Linney’s plot does not have those moments of joy. So Laura Linney’s life is continually interrupted by mysterious phone calls, which we then learn, during an attempt to consummate this crush she’s had on a coworker–

Josh: Karl.

Alexandra: Why is everyone–Why can you only bang the people you work with in this film? I think that it’s really uncomfortable. Stop having so much sex with your coworkers.

Molly: Agree.

Corey: So she gets these two calls from her brother who is clearly mentally disabled. And it becomes clear that she is going to take these calls rather than continue and just, sidebar, Karl can go to hell.

Josh: He gives her one call and then after that he’s done.

Corey: He disappears from this movie. Does he appear at all? Like, he is gone.

Josh: There’s one other scene where they’re at work and he says good night and she says good night. Which implies they are not going to continue this.

Molly: And I think it’s implied that like, he said this and had Laura Linney said more, he would have deigned to, like, “take her back” and I’m putting that in quotes. But she doesn’t. She effectively shuts him off and she just says “goodnight Karl” very efficiently and cheerfully and that’s that.

Alexandra: Her mentally disabled brother is really posited as, rather than being a joy in her life, as being this like horrendous burden that she will never be able to put down.

Molly: I disagree. I think she really loves him. There’s also that scene–

Alexandra: No, I’m not saying she doesn’t really love him. I’m just saying that the film treats it as this life-altering tragedy that she will never be able to escape from. Your booty call can’t wait 10 minutes for you to talk on the phone? That is absurd to me.

Molly: But she’s making a choice to take those phone calls. There’s also the scene on Christmas, she goes to wherever he lives, and she gives him like a scarf or something? And he gives her this big hug and it’s a true, like, she really loves him and there really is love there.

Corey: But then he tries to hit her, right? And there’s a way–

Molly: in a different scene.

Corey: But there’s a way to show this relationship that can show both the labor that she is doing and the love that she’s getting out of it, and I don’t know that it gets that balance right.

Alexandra: I want to know what is going on with Karl. Why could he not wait? What is wrong with him? Or is he–

Corey: or try another night? But yeah–

Alexandra: Try another night. Just I mean–

Josh: Well, his character trait is being attractive. So it’s hard to gesture at what his subject position really is.

Alexandra: That’s fair. So what you’re saying is that women are–I just almost said something so inappropriate. Holy cow.

Molly: Say it, we’ll edit it out.

Alexandra: Basically, what you’re saying is that women are just so keen to throw their pussy at him that one night is too long to wait because someone else will–

Josh: I think Karl has been acclimated to a certain standard.

Alexandra: Alright. I will actually believe that if he leaves that apartment, someone else will just immediately try to have sex with him, in the terms of the film.

Molly: Karl is trash. I’m not making the argument she should have picked Karl.

Alexandra: No, no, I’m not either.

Corey: No, I actually think that your reading of that scene is persuasive that when she shuts him down–I just think the relationship with the brother could have been depicted in a more meaningful way.

Molly: All right. But I’m still going to make the case that we’re not meant to feel sad for Laura Linney. I genuinely believe–

Alexandra: Oh, I don’t know about that. I think we are.

Corey: I think we are meant to feel very sad.

Josh: We’re supposed to feel that she is selfless, that she’s sacrificing her happiness for her brother, which is a beautiful gesture. But she is left out in the cold in this, you know, in the economy of the film, she’s not partnered off. She’s sort of in this–

Molly: Well, she’s an American, so–

Alexandra: Which is probably why she’s wearing that winter hat in the wedding, she’s been left out in the cold.

Josh: That’s right.

Alexandra: One thing that’s shocking to me, though, in this conversation is how little we’ve actually been talking about Christmas, which leads me to whether or not this is even really a Christmas film?

Corey: I don’t think it is.

Molly: It’s a 19th century novel set against the backdrop of Christmas, with all the chance encounters, the vagaries of urban life, the weak but real connections.

Josh: Interestingly, the film posits the argument that Christmas is a season of honesty and I was wondering what the origins of that are. We see that in that same scene with the confession of love to Keira Knightley’s character, and you get it in the postcard from Natalie to Prime Minister Hugh Grant, you get these references, like, well it’s the Christmas season so I have to be honest about who I love, which–

Molly: That’s not true. It’s not the season of atonement, like that’s not what Christmas is. We actually do have that built into Abrahamic religions and it’s not Christmas.

Alexandra: Damn, that is, like, an indictment against the film right there. Maybe not intentionally.

Josh: They should have made a Yom Kippur-themed Love, Actually.

Molly: Yeah.

Corey: I mean, we are–We’re moving through holidays for these anthology films, right? This sort of–you’re right that this idea of sort of an interconnected community goes back at least to the 19th century novel. But jumping out from this movie, we’ve had a series of, I would say increasingly less successful movies with similar structures. There’s, help me out, there’s–

Josh: Valentine’s Day?

Corey: Valentine’s Day, there’s He’s Just Not That Into You. There’s New Year’s Eve. Yeah, there’s–is there–

Alexandra: I want to take it back, though, because this is also the structure of a film from much earlier than this called 200 Cigarettes.

Corey: Oh, yes. Talk about 200 Cigarettes.

Alexandra: Oh, I don’t remember much about it. Except that it’s like a sort of seedy club, nighttime, see a rock band, party culture thing, but it’s a set of interconnected stories. I think it’s actually also New Year’s Eve in that film. Wow. Factcheck me on that.

Corey: Wait, is that Go? Because Go is similarly structured,

Alexandra: It’s not Go that I’m thinking of, because I know Go much better than I know 200 Cigarettes but that is also similarly structured.

Corey: Is Go New Year’s Eve, though?

Alexandra: No.

Corey: It’s just a big rave night.

Alexandra: It takes place over sort of like a whole weekend and it’s just a big party weekend. There’s no reason for it. Someone is getting married, which is why they end up burning the hotel down in Vegas.

Corey: I need to rewatch Go.

Alexandra: Actually, now that I think about it Go might be set at the Christmas season, though.

Corey: I think you’re right. This is a conversation that only we are having.

Josh: Can I make what might be a controversial argument in terms of the genre of this movie?

Alexandra: Please.

Corey: Yes.

Josh: Given what we’ve been talking about: I don’t think it’s actually a Christmas movie. What I think this movie really is, is a post-9/11 movie. And I just re watched it last night for the purpose of this podcast. I hadn’t seen in a while, and I had completely forgotten that in the opening minute, 9/11 is invoked by Hugh Grant doing the voiceover. Of course the movie is framed by these airport scenes, right? Shots of people reuniting at the airport. And the end of the boy’s storyline, he’s chasing down his crush, she’s getting on this plane to America. And of course, you know, it’s very dramatic and he gets there right before she gets on and whatever, they have their moment. So there’s this chunk of the movie at the end that’s in the airport, it opens and closes with the airport, but specifically 9/11 is mentioned by the voiceover in the beginning. What I think this movie actually is, is saying–using love, using themes of Christmas to actually convey the world is safe again. It’s okay. It’s okay to open up to people, love is still out there. The world, you know, it’s 2003. We were coming out of this trauma of 9/11 and–

Molly: And we’re about to invade Iraq. I think this is also an Iraq war movie.

Josh: Sure, fair.

[Clip]

Prime Minister: I love that word relationship. Covers all manners of sins, doesn’t it? I fear that this has become a bad relationship. A relationship based on the President taking exactly what he wants, and casually ignoring all those things that really matter to Britain. We may be a small country, but we’re a great one too. Country of Shakespeare, Churchill, The Beatles, Sean Connery, Harry Potter, David Beckham’s right foot, David Beckham’s left foot. A friend who bullies us is no longer a friend. And since bullies only respond to strength, from now onward I will be prepared to be much stronger. And the President should be prepared for that.

[End Clip]

Molly: It’s this, like, reclaiming of Britain as an imperial power, right? Like, “we are strong enough. We don’t have to shackle ourselves to the Americans. We’re a great country and we can do good things.” And that’s in quotes because the movie understands imperialism to be a good thing, which I do not. But it’s a wish fulfillment about Tony Blair in the lead up to Iraq.

Josh: Yeah. 100%.

Corey: The movie thinks that British imperialism is good, American imperialism is bad. And American politicians creeping on their subordinates is bad, and British politicians creeping on their subordinates–

Molly: And maybe that’s how we read the American women’s storyline too. Like, they’re just dumb and silly and they need to be conquered by a British man and brought back to Britain.

Alexandra: Which also, I think is one of the reasons that Aurelia is Portuguese, even if she’s in France. Because you can’t make the same sort of claim about Britain’s relationship to France, because it’s more fraught.

Molly: Yeah. Okay. All right.

Alexandra: 1066.

Corey: Yes.

Molly: I still don’t understand why they couldn’t just have him go to Portugal, but–

Alexandra: I don’t know anything about British history at all.

Corey: But you’re right, 1066. The only colonial subject that comes out of this looking good is Joni Mitchell. Right?

Alexandra: Yeah, absolutely correct.

Molly: So this might be a 9/11 or an Iraq war movie, but like it at least sells itself as a Christmas movie, right? Which begs the question, like what makes something Christmas content?

Alexandra: Absolutely. Well, I really liked–I looked up this sort of work by Judith Flanders. She wrote a book called “Christmas: A Biography,” which I thought is really interesting. And one of the arguments that she makes or the claims that she makes is that–I’m going to read this: “Our Christmas rituals honor not the lives of we have, but the lives we would like to have in a world where family, religion, personal and social relationships are built on firm foundations. Even though that world never really existed, the true magic of the holiday season is that by repeating the rituals, we can go back there every year.” What do you guys think?

Josh: Absolutely. Yeah. I think it’s 100% accurate.

Molly: It’s a way of honoring tradition and rituals in a secularized world.

Alexandra: Absolutely.

Corey: And I think it’s, I think it makes sense why you would dovetail this with post-9/11. Right. This is a ritual to get back–

Alexandra: To get back to normalcy.

Corey: And when you think about what Americans were instructed to do in the aftermath of 911 was to go Christmas shopping. Like, like, go shop. Go spend money. Buy plane tickets. Fly again.

Molly: “They hate our freedom.” So show it to them by going all out for Black Friday.

Alexandra: Shopping. Yeah. Which is very interesting. And maybe after the break we can talk about how this is all sort of a take on Charles Dickens and A Christmas Carol and the hangover of A Christmas Carol in Christmas content going forward.

[Ramblin’ Wreck car horn]

Corey: This weekend I saw a new film, Last Christmas, which has been out in theaters for a couple of weeks. And if you watch the–the trailers and the footage for this movie, it kind of seems like it’s in the lineage of Love, Actually. It’s set in London at Christmas time. Emilia Clarke who plays the lead is constantly dressed in this embarrassing elf costume. And it seems like a rom-com but halfway through there’s this twist, and I don’t want to give away the twist, but it actually becomes A Christmas Carol midway through. And we retell A Christmas Carol so often. FX is releasing a new like ghost/dark version of it. And so I thought we could talk maybe about kind of what is it about A Christmas Carol? What versions do we return to in our own rituals? To kind of get at why this story in particular kind of defines Christmas so much for us.

Alexandra: Before we get into our versions of it, I would like to hear what do you think–What is the content of A Christmas Carol? Like, what does it give us at the Christmas season? What does it tell us? The original version.

Molly: That we can be better people. It’s never too late.

Corey: Without working particularly hard

Molly: Which is not the original Christian message of Christmas.

Alexandra: I can go to sleep and I can wake up as a better person.

Molly: Yeah.

Corey: Yes. And also, if that happens, we can solve larger social, right–larger social problems can be solved through individual reformation.

Molly: Yeah, it’s just a reformation of belief. You just have to reform your soul. You don’t have to actually do any acts or deeds to become a better person.

Alexandra: This is deeply Protestant then.

Molly: It’s deeply–It’s Charles Dickens!

Alexandra: Again, I don’t know anything about British history!

Molly: If it’s a 19th century Brit, you can fairly assume it’s Protestant.

Corey: Yes, yes. Yeah. So–

Alexandra: Okay, so then what are our favorite versions of this and what things from the stories do they bring to the front or make an argument about?

Molly: I deeply love–I don’t want to call it like a ritual. I don’t watch it every year, but I grew up on Scrooge, the Albert Finney Scrooge version. And I love that one mostly ’cause it was terrifying. Have you guys ever seen it?

Alexandra: You showed us a clip of it and I found it to be confusing and horrifying. And speaking of like, grim and dark, I know this is not what we think of like we’re talking about a different kind of aesthetic, grim-dark thing, but I found it to be foggy and cloudy and exceptionally brown.

Molly: Well, it’s Industrial Revolution London. Yeah. But the way they do–honestly, if we watched it as adults, we probably want to be afraid–but the way they do the Ghost of Christmas Future gave me nightmares as a child and I liked that. That’s what I wanted.

Alexandra: You wanted to be terrified?

Molly: Yes. And it did a very good job of that. Again, yeah, there was something about this like “you had to suffer in order to become a better person” that was sort of deeply appealing to my childhood.

Alexandra: Interesting. I actually really like–I don’t know that I would say that they’re versions of Christmas Carol, but maybe they are but I love Christmas horror movies. So like the movie Krampus for example, starring Adam Scott and Toni Collette, directed by a gentleman who did his previous movie was Trick ‘R Treat, which is a Halloween horror anthology kind of movie with all these interconnected stories. Krampus is much more linear than that. It’s not really interconnected stories, but it is genuinely about, like, just scaring the shit out of people via Christmas and all the sort of weird and terrible things that Christmas could bring to you, including a hooved devil monster who would simply murder you.

Corey: Well, yeah. And it’s sort of this idea of reform, right, you can bring around reform with a carrot or a stick. I think that Futurama plays with this in its version of Christmas. Futurama, the Matt Groening scifi cartoon. Am I the only one who–

Alexandra: I’ve seen episodes.

Corey: Okay, so it’s set 1000 years in the future and in this particular future, they tried to build a–robots are sentient–they tried to build a robot Santa Claus but they mis-set his morality meter. And so rather than giving presents to good people, he violently murders bad people. So everyone spends the Christmas season hiding from this patrolling murderous robot Santa Claus.

Alexandra: I do actually think I’ve seen this and it’s brilliant and in part it takes us back to the Christmas tradition pre-Dickens, right? Because Christmas used to be or–maybe pre-America even is what I want to say there–before the kind of consumer fetish festival

Josh: Coca-Cola.

Alexandra: Yes the Coca-Cola polar bears and shit like that. Christmas was about like deeply horrifying people and making them hide out because they had been bad people all year long and they were going to be–it’s like in the Netherlands, right, where Santa has like six to eight black men who ride with him and they just like whip people. The Office did a version of this with Belschnickel.

Corey: Yes, yes, With Dwight, right?

Molly: Until like, about Dickens’ time, Christmas was not nearly as big of a deal as Easter. The cultural emphasis on Christmas is fairly new.

Corey: Yes. And Christmas Carol was in this known genre of Christmas creepers, right, these sort of Christmas horror stories which survives past Dickens. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was a Christmas tale, right? It was sort of, and these were very lucrative publications. Both Christmas Carol and Jekyll and Hyde got their authors out of debt.

Alexandra: Valancourt Books actually has a series of anthologies that they release every year at Christmas now. They’re on their third one. And what they do is go back to these 19th century British periodicals and pull out Christmas ghost stories and then package them all together as like The Valancourt Book of Christmas Ghost Stories. There’s three of them that you can purchase.

Corey: I am adding them to my Christmas list. My favorite Christmas Carol adaptation is a slightly different direction. it is The Muppet Christmas Carol. Although there are moments of this that are creepy, the ghost of Christmas future is rather creepy in this.

Alexandra: Is that the one that is always a little girl?

Corey: No, the little girl is the Ghost of Christmas Past, and she’s actually–The Muppet Ghosts of Christmas Past is also spookier than she is often. She has this sort of ethereal presence. It’s a little bit uncanny and frightening. It also features Michael Caine as Ebenezer Scrooge. And it is–if there was an Oscar for Best Performance Opposite Muppets, he wins it hands down. Because at no point does he play it any way other than straight. You could just like, take him out of this movie and film live action actors around him in a new Christmas Carol and it would work. He–

Alexandra: That’s the magic of puppets.

Corey: He acts alongside Kermit the Frog as Bob Cratchit like it was another actual physical actor.

Alexandra: This is genuinely one of Jim Henson’s theories of puppetry, is that–one of the things that he noticed in working on the Muppets and Sesame Street is that, it does not matter the age of the person, it does not matter what they’re doing, who they are, what their level of experience is, if you talk to them as a puppet, they will only pay attention to the puppet, they will be so invested in the sort of suspension of disbelief, completely just like leaped over the uncanny valley. And they will just act as though the puppet is the real thing that’s talking to them and ignore the puppeteer.

Molly: Werner Herzog apparently has been walking around the set of The Mandalorian talking to Baby Yoda as if it’s a real creature.

Alexandra: That is number one the most Werner Herzog thing I’ve ever heard in my life, and number two, it is amazing and I want that behind the scenes footage.

Josh: If you subscribe to Disney Plus I’m sure you can get it.

Corey: Give it a few months, whenever that first year of subscriptions are running out they’re gonna give you all the Werner Herzog. But so you have Michael Caine doing this, like, very straight Ebenezer Scrooge. And then you have Muppet nonsense around him. And it is, it is lovely. So Gonzo plays Charles Dickens, narrating the story, and he’s accompanied by Rizzo the rat who is constantly disrupting the fiction and saying “no no no, you’re not Charles Dickens.” I have a clip.

[Clip]

Gonzo (as Charles Dickens): Get ’em while they’re fresh.

Rizzo: Apples! Christmas apples!

Gonzo: We got Mclntosh!

Rizzo: Get your Christmas apples.

Gonzo: Red Delicious.

Rizzo: Tuppence apiece while they last.

Gonzo: We… They won’t last long the way you’re eating them.

Rizzo: Hey. I’m creatin’ scarcity. Drives the prices up.

Gonzo: Rizzo! … [to audience] Hello! Welcome to The Muppet Christmas Carol. I am here to tell the story.

Rizzo: And I am here for the food.

Gonzo: My name is Charles Dickens.

Rizzo: And my name is Rizzo the Rat… Hey. Wait a second. You’re not Charles Dickens.

Gonzo: I am too!

Rizzo: No. A blue, furry Charles Dickens who hangs out with a rat?

Gonzo: Absolutely!

Rizzo: Dickens was a nineteenth-century novelist. A genius!

Gonzo: Oh. You’re too kind.

Rizzo: Why should I believe you?

Gonzo: Well. Because I know the story of A Christmas Carol like the back of my hand.

Rizzo: Prove it!

Gonzo: All right. Um. There’s a little mole on my thumb and. Uh. A scar on my wrist…From when I fell off my bicycle.

Rizzo: No. No. No. No. Don’t tell us your hand. Tell us the story.

Gonzo: Oh. Oh. Thank you. Yes. “The Marleys were dead to begin with…”

Rizzo: Wha- Wha… Pardon me?

Gonzo: That’s how the story begins, Rizzo. “The Marleys were dead to begin with. As dead as a doornail.”

[End Clip]

Corey: This plays throughout the movie, but then that same kind of spirit runs through the scenes that they aren’t–that Charles Dickens is not invested in. So instead of just Jacob Marley, there are two Marley’s and it’s Statler and Waldorf obviously. And Michael Caine responds to their appearance with a direct quotation from Charles Dickens, this really great joke that is–or, a joke that Dickens writes–and Statler and Waldorf heckle him.

[Clip]

Scrooge: Who are you?

Jacob Marley: In life. we were your partners. Jacob…

Robert Marley: And Robert Marley!

Scrooge: It looks like you. but I don’t believe it!

Jacob Marley: Why do you doubt your senses?

Scrooge: Because a little thing can affect them. A slight disorder of the stomach can make them cheat. You may be a bit of undigested beef, a blob of mustard, a crumb of cheese. Yes. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you!

Jacob Marley: “More of gravy than of grave”? – What a terrible pun.

Robert Marley: Where do you get those jokes?

[End Clip]

Corey: We have these Muppets heckling Charles Dickens. And it’s this equal part respectful homage and just, like, taking the piss out of Charles Dickens and I love it so much.

Alexandra: I feel like that as an adaptation is truer to the spirit than the most like straightforward, bare-faced Dickens adaptation, right? In much the same way that in Molly’s version, what’s it called Scrooge?

Molly: Yeah.

Alexandra: “Thank you very much” is an astonishing document.

Molly: “Thank you very much” is incredible. If you’ve never seen the Albert Finney–

Corey: Will you explain it? And then we’ll–we’ll, we’ll transition with a clip.

Molly: Oh, it’s, I think it’s in the timeline of the ghost of Christmas present. Or maybe its future. It’s either present or future.

Corey: It’s future. It’s got to be, given the plot of the story. It’s got to be.

Molly: Okay. So it’s, okay. It’s future, and the ghost of the future takes Scrooge to see–oh, I’m sorry, the other thing about the ghost of Christmas future in this adaptation is he does not speak, he just ominously points at things. So he takes him to the street where Scrooge has offices, and Scrooge lives above his office, right? That’s part of it. Doesn’t matter, anyway. And Scrooge is like, “oh, look at this. This is my street. Oh, my gos. There’s the Cratchits. There’s the old lady, what’s going on?” And he realizes that everybody in the street is thrilled. It’s like a party, and he doesn’t really understand what’s happening. And Bob Cratchit starts singing this song: “Thank you very much. That’s the nicest thing that anybody’s ever done for me.” And everyone starts breaking out in this coordinated dance, because it’s also–the movie is a musical. And everyone starts breaking out in this coordinated dance. And it’s almost the end of the song that Scrooge realizes what they’re all celebrating and what they’re all thanking this mysterious benefactor for. They’re thanking Scrooge and the nicest thing that anyone’s ever done for him is die. They’re serenading his coffin.

Alexandra: I believe he dances on the coffin at one point.

Molly: Yes, he does.

Corey: We watched this clip. I did not realize it was Bob Cratchit. I love that there’s a salty Bob Cratchit in this edition. It’s, that is fantastic.

Molly: Yes.

[Clip]

[over music] Ladies and gentlemen On behalf of all the people who have assembled here I would merely like to mention if I may That our unanimous attitude Is one of lasting gratitude For what our friend has done for us today And therefore I would simply like to say [begins singing] Thank you very much! Thank you very much! That’s the nicest thing that anyone’s ever done for me I may sound Double-Dutch But my delight is such I feel as if a losing war’s been won for me And if I had a flag I’d hang my flag out To add a sort of final victory touch But since I left my flag at home I’ll simply have to say Thank you very, very, very much! Company Thank you very, very, very much!

[End Clip]

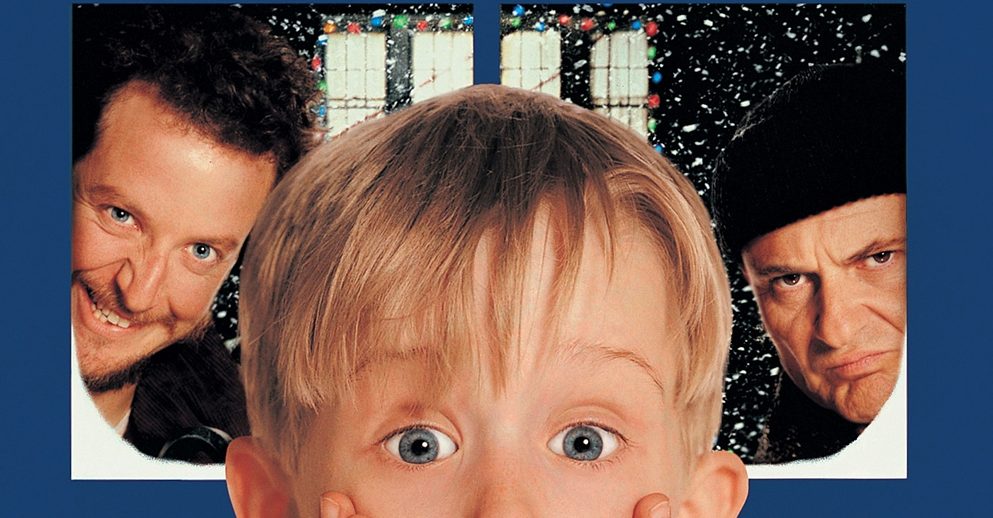

Corey: So on that note, we’re going to take one last break and come back to talk about another adaptation of Christmas Carol, that has, in some ways defined our generation: Home Alone.

[Ramblin’ Wreck car horn]

Molly: In the last segment we’re going to talk about today, we are going to talk about the classic 1991–1990 film, Home Alone. And I think we wanted to start by looking at this, maybe not even necessarily as a Christmas movie, but as a way of sort of expressing maybe late 80s, early 90s white American anxieties.

Alexandra: Absolutely. Yeah, absolutely. I just rewatched it and I was shocked at how much the plot of Home Alone, which, I mean, if you don’t remember, Kevin McAllister is living in this gigantic house in suburban Chicago.

Molly: It’s in Wilmette.

Alexandra: It is so large, Molly, why?

Molly: Because Wilmette is extremely wealthy. When I was in a child/into high school I was a competitive swimmer and almost every year Wilmette hosts the Illinois High School championships and it was a ritual that after the state meet was over every year our coach would take us in the giant van we had driven out to Wilmette and we would get to see the Home Alone house.

Josh: That’s a great ritual.

Alexandra: Oh, it’s like a real–it’s there? It’s just there, in Wilmette?

Molly: Yeah, yeah. We would like be in this van, like we’ve rented a van, like it wasn’t a full bus because it was the state meets, we didn’t have any people going and we would go in this large passenger van. And as I remember I think we just drove down the street and were like, there it is. That was it.

Corey: Was the lawn jockey that gets knocked over still there?

Molly: You know, I don’t know that I ever looked. I either never looked or I have forgotten.

Corey: Yeah, that’s fair.

Alexandra: That’s a weird running gag. So Kevin McCallister is in this house with his entire family, his extended family, and they’re all getting ready to go to Paris for the holiday season. The next morning, the power goes out and they all oversleep. So they’re in a rush, and they accidentally count a neighbor kid who does not make it onto the van, the van to the airport with them.

Molly: Which also makes no sense that this would be happening in the morning, because flights to Europe from Chicago leave in the late afternoon. They leave like five or 6pm.

Alexandra: But it is 8am when they leave for the airport.

Molly: Yes. Which makes absolutely no sense unless they had an insanely long layover in like Philadelphia or New York, which you can get direct flights to Europe from Chicago and this family is extremely wealthy, so I don’t buy that for a second.

Corey: And it’s depicted as a direct flight right? Because it’s when they land that they realize he’s missing.

Molly: I would just like to note that that makes no sense but let’s carry on.

Alexandra: Alright. The entire family–14 people–go to Paris and Kevin gets left home alone, as they say repeatedly. The family then–his mom, played by Catherine O’Hara, does everything in her power to get back immediately. She bribes people, she ends up taking a ride with the polka king of the Midwest

Molly: From Sheboygan.

Alexandra: From Sheboygan, to get back to Chicago. And the rest of the family arrives back in Chicago actually, at the same time as her, positing that all of her labor was, or her effort, was useless.

Corey: The rest of the family does not care.

Molly: They laugh at her.

Corey: Even Kevin’s father does not care.

Molly: That’s because he’s a mobster.

Alexandra: Absolutely. So while Kevin is home alone, right, he ends up finding out that these two criminals are planning to rob all the houses in the neighborhood. And he foils their attempts to rob the household.

Molly: Including with a cardboard cutout of Michael Jordan. This movie could not be more 1990s suburban Chicago.

Alexandra: Absolutely true. And a lot of mannequins for some reason, I’m confused as to why they have so many mannequins.

Corey: There’s a ton of mannequins in the basement.

Molly: It’s probably used in his nefarious gangster deeds, maybe they’re, like, shotgun targets.

Corey: So just to back up, Molly has a theory about Kevin McAllister’s dad and why they live in this massive house.

Molly: He’s a mobster.

Alexandra: So having just rewatched it, I was looking for this thread. And it is true that this is a moment of peak late 80s, early 90s whiteness where you could be that wealthy in a film, and no one has to explain it. There is no explanation as to why these people have so much money. And yes, they have like four or five children. But that house is, I mean, conservatively several million dollars.

Molly: Correct. You have to have space to entertain your mob buddies.

Corey: Yes. And yet two of these children have to sleep in the attic for some reason.

Molly: Yes.

Josh: Because they love them less.

Alexandra: Right. Well so what I was noticing is, rewatching the film, is that it is absolutely about the late 80s/early 90s growing cultural fear about the trend of latchkey kids and working mothers. Though we don’t know what Catherine O’Hara and her husband do, she is presented as a kind of a professional woman. She has that camel coat, she has her nice earrings. She has her perfectly coiffed hair all of the time, right? She seems–her bag is almost like an attache case. She seems sort of professional in a way, I could imagine her being a lawyer or a doctor of some kind

Molly: For the mob.

Alexandra: Possibly for the mob. I’m not discounting the mob theory, I’m just saying that the film is expressing a very deep cultural anxiety that–what ends up happening, by the time, I would say not my childhood because my childhood was right around the same time but just a couple years after this, is that people stop allowing their children to be latchkey kids. And I feel like it’s because of movies like Home Alone, which posited the worst thing you could do is leave your child home alone.

Molly: Where there would be a home invasion. Yes.

Corey: Right.

Molly: Is there ever a threat that they’re going to kill him? Or is it always just property damage?

Corey: Oh, no, they, towards the end, they start to threaten him physically. Because he has, he sets these booby traps.

Alexandra: Well, he has injured them physically. First. Before–they simply want to rob the house. They’re convinced–to go along with your mob theory–they are convinced that there’s a horde of cash in this home for some reason.

Molly: Yeah, it’s the “big tuna” or whatever. Isn’t that what they call it?

Corey: Yes, so they, just in the first of many mistakes that these criminals make.

Molly: They’re very bad at being criminals.

Corey: Before anyone leaves town Joe Pesci poses as a policeman, which I believe is a federal crime, to visit every single house to case the joint, under the guise of like checking to see if they’re being safe over the holiday. So this is, he figures out when–

Josh: You know, your annual visit from a cop to see if your house is safe. So normal.

Corey: And this is posed by the film as like this genius criminal move. It is not. But within the logic of the film, this is how he knows who’s home and who isn’t home, who has timers on their lights and who doesn’t. But Kevin McCallister is constantly throwing a wrench in this, but yeah, I don’t think there are ever threats of physical violence until Kevin McAllister starts hurting them.

Alexandra: He absolutely–I mean, one of the very first things that he does is drop a hot iron on Daniel Stern’s face.

Corey: Oh, he shoots him with a BB gun.

Alexandra: You’re right. Yeah, actually, you’re right. That is one of the very first things: shoots him right in the nuts with that AirSoft pellet rifle or whatever.

Molly: And then he walks down the stairs and he steps on a nail in his bare feet, right?

Alexandra: He does.

Molly: Cause for some reason he’s barefoot.

Alexandra: Oh, it’s because Kevin has covered the basement steps in tar and that’s why, first you see his shoes stuck to the tar, then you see his socks stuck to the tar. And then he puts his bare foot on to the nail. There is a lot of like, the ratcheting up of the, like, booby trap situation is–it starts at a 10.

Corey: Yes. Yes. And then it goes up from there. But these criminals are played by Joe Pesci and Daniel Stern. 1990, so Joe Pesci, as this movie is making like $300 million, Joe Pesci is also about to win an Oscar for Goodfellas which had just come out. So like there is this sort of like, you bring Joe Pesci into your film. And I mean, obviously he doesn’t quite have the–He swears like Yosemite Sam does, rather than, like, Joe Pesci’s character in Goodfellas, whose name I’m blanking on. But there is this kind of, like, sense of organized crime underneath this. There’s this whole subplot with a fictional film that exists in this universe called Angels with Filthy Souls that’s this exploitative mobster film, like black and white.

Alexandra: Oh, I actually will say, I was yesterday days old when I realized that this film was not real, which is astonishing, because if you don’t know, I study early 20th century film. It is, shot for shot, a perfect 1930s gangster film. There is like one moment where the camera does something that you’re like, actually, that is not cinematographically what a 1930s gangster film would do, like that’s not how framing would work. But it is almost perfect. To the point that I genuinely believed until I looked it up like yesterday that it was real. But it’s a play on Angels with Dirty Faces, which is Humphrey Bogart.

Corey: Yeah,

Alexandra: But it’s of course much more–the talking in the film is much more violent than–you wouldn’t really say those things in a 1930s gangster film, it’s heightened.