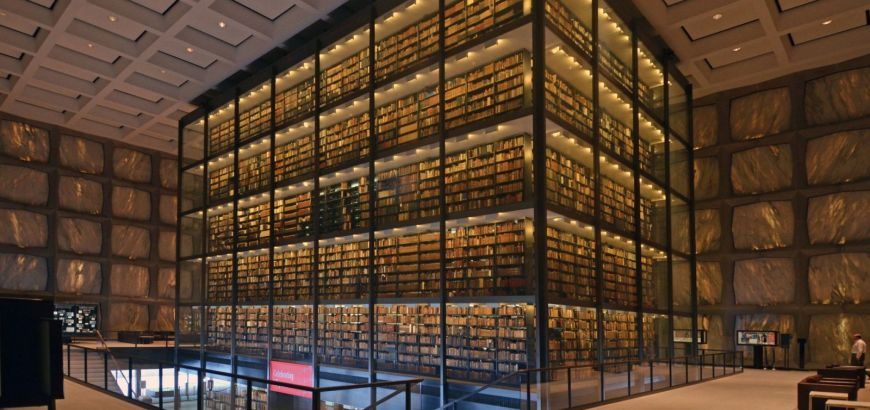

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. Photo by Michael Marsland.

Archives, research libraries, and special collections are the crucial spaces where study begins. While public and school libraries hold a space in the popular imagination as a catalyzing site of intellectual curiosity—as seen in the recent piece “12 Authors Write about the Libraries They Love” in The New York Times—archives are an equally important space for exploration. Rather than stuffy academic repositories, archives are living environments that open onto the past. As poet Susan Howe describes in Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives, the reading room is the scene of “deep memory’s lure, and sheltering. In this room I experience enduring relations and connections between what was and what is.”

These 16 portraits of current and former Brittain Fellows’ experiences with archives are notes of love for the collections, archivists, and surprises that have helped form the unique range of scholarly and professional interests that define the Brittain Fellow faculty of the Writing and Communication Program at Georgia Tech. Material and digital, at home and internationally, following the meticulous and the serendipitous, these recollections track experiences with everything from comics to cookbooks, pinball machines to paleography, and marginalia to murder to modernist meat. The editors of TECHStyle are thrilled to offer this collage of archival experiences, which has become its own special collection.

Adventures in Comics Wonderland

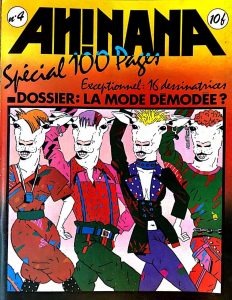

Ah! Nana, 1977. Cover art by Nicole Claveloux: “16 women cartoonists / Dossier: Is fashion becoming unfashionable?”

Comics studies would not exist without Randy Scott, the archivist responsible for the Comic Art Collection at Michigan State University. The Rare Book Room at MSU is located in a basement, behind several large metal shelves full of periodicals and an institutional wooden door that could lead anywhere. Like Alice’s rabbit hole, it is unassuming. But inside is the wonderland of comics history. Randy, with his long white beard, is your guide. Sure, you have to fill out your request card, but you will be sitting there, entranced by the advertisements that get left out of edited collections, or captivated by a comic that has never been reprinted, and another box of comics will appear on your table. The comics in this box will be ones that maybe only Randy remembers, but, when you go to inquire about the box, he will tell you how they are connected to your research.

This is exactly how I discovered Ah! Nana, a French series of underground comics by women from the 1970s that Randy pulled out because it related to the Wimmen’s Comix series, an American series of underground comics by women in the 1970s, that I had come to MSU to visit. Never translated and never reprinted, Ah! Nana could potentially be lost to history if it weren’t for Randy. I sat there that day and read and translated the comics in Ah! Nana. I was enthralled by the beautiful artwork of Nicole Claveloux and Cécillia Capuana and shocked to see translated versions of comics by Trina Robbins and Sharon Rudahl that originally appeared in Wimmen’s Comix. Randy opened up an avenue I didn’t even know existed, reframing my view of underground comics, usually written about as an American phenomenon, as an international movement.

I have since discovered network connections between American underground comics and underground comics in such countries as Italy, Japan, Germany, and (most recently) Australia, all of which began shortly after the appearance of a local youth movement and all of which draw on the idiom created by the distinctly American form of underground comics. Curiouser and curiouser. Why did this medium, generally associated with children, suddenly become a global countercultural mainstay associated with sex, drugs, and rock and roll? What technology or phenomenon gave American culture such global reach at the time? I would not even know to ask these questions without Randy and his collection at MSU.

When I drove to Lansing in the middle of February to visit Ah! Nana, as I was diligently photographing pages for an upcoming talk and translating the French into English, another box appeared on my desk. This time it was full of Le Canard Sauvage, another French underground series from around the same time that included contributions from women I learned about in Ah! Nana, which has also never been translated or reprinted. And down the rabbit hole I went.

—Leah Mismer, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Archives of Play

Panoramic photograph of the archives at The Strong Museum of Play, Rochester, NY.

Distraction can bedevil the archival researcher. Indecision arises from too many resources. Diversion waits on the smartphone used to take one’s reference photographs. And to have a historic pinball arcade of national significance beneath the reading room can easily tempt one away from intended labor. Happily, at The Strong Museum of Play—which houses a world-class archive of games, toys and their related ephemera—distraction can qualify as research.

I visited The Strong in support of a book manuscript, Media Cartography: The Cinematic History of Mapmaking, which takes as its premise Fernand Léger’s observation that “the cinema and the aviation go arm in arm through life; they are born on the same day.” The joint arrival of film and air travel had repercussions for countless media—including postcards, games, and maps—that began to move in time with the new rhythms of these machines. At The Strong, I examined miniature moving panoramas that unrolled narrative canvases against an endless horizon; “dissected maps,” the early form of jigsaw puzzle, which in the early days of aviation gave way to cartographic board games; and many other bits of ludic aeronautica.

Historians of science have for some years now been recreating historic scientific experiments using period equipment, in order to recover and demonstrate “knowledge in action,” as embodied in artifacts and experience. Likewise, to capture the echoes of this past media moment, when cinema and aviation prompted a new culture of movement, one cannot simply read about the history of games and toys; one must play them as their original users might have, and activate these objects afresh. Roll the dice. Pick the card. Push the button. Less familiar actions are also waiting to be revived. Dangle the magnet. Unfurl the roller. Tilt the whole pinball machine.

—Patrick Ellis, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Don’t Forget the Ritual

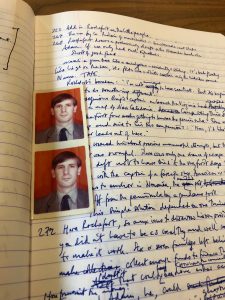

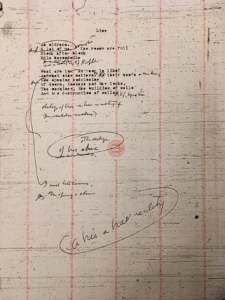

From the Douglas Oliver Archive. Courtesy of Albert Sloman Library Special Collections, University of Essex.

Archival work makes scholarship a kind of ritual. I travel to these collections, devoted and curious, to start a conversation. At the University of Essex, I’m transcribing lines from Douglas Oliver’s notebooks—“Politics begins then in this pink desert,” “The self as shining,” “Take the prose and I’ll music take the prose and I’ll make some real thing in music,” “Don’t forget the ritual”—a pigeon cooing outside the large windows of the Albert Sloman Library’s Reading Room. The entirety of the Oliver Archive is stacked in front of me in uniform blue archival boxes. Always in archives I have this sense of presence gathering. Alice Notley will tell me later, “I read all of the poetry books in that library that Tom Clark hadn’t already stolen.” Pieces are absent. A narrative fragment glistens. I scribble a note, take a picture on my phone, lean over another page. This is the ritual, the way that scholarship stays close. This proximity, I think, is also the process of scholarship becoming generous.

Other than the address of the house where Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley lived in the mid-‘70s—during a brief British sojourn while Berrigan was teaching at the University of Essex—I have no plans on where to go in Wivenhoe. Nevertheless, it felt important that I stay in this little riverside town for a few days to trace out the feeling of the inconspicuous village that in the 1960s and ‘70s had been home to a surprising number of American poets. Oliver had been Berrigan’s student at Essex, and a close friend of both Berrigan and Notley. Later, after Berrigan’s death, Notley and Oliver would start their own life together, including editing two poetry magazines together, and many of the notebooks in his archive date from the early years of their marriage. Notley’s handwriting often appears throughout Oliver’s pages, usually as lines in wayward, casual poems between the two. “Invent / The way we’re with,” she writes. A correspondence takes hold in the repeated return to material presence. A color photo booth image of Oliver slides quietly out of his notebook—red background against blue ink. I hold it for a moment, then fold it back in.

Between lunch at The Black Buoy and walks on the quay, I’m reading Oliver’s Whisper ‘Louise’, an experimental memoir that tracks his own life parallel to the life of French Communard heroine Louise Michel—a narrative alignment of disparate sources. The unlikeliness of the alignment is what makes the book curious, vital. Scenes of his and Notley’s life together in New York City and Paris are bound up in it. Oliver describes how he used to sail up the river through Wivenhoe, wonderfully near the sea. Along the river in the evening, I’m following my sources. The narrow side streets cutting up the hillside are spilling over with hollyhocks, green figs, and lilac. Leaving Wivenhoe to return to London the train, like a ritual, passes through fields of lavender. The windows are filled with a purple wash. An archive, the color of studying.

—Nick Sturm, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Haggard in Full Color

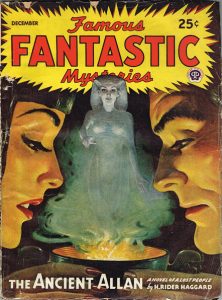

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, vol. 7, no. 1, December 1945, by H. R. Haggard.

Like many academics, I apply for far more grants than I receive. This has been particularly true when it comes to research library travel grants. Mercifully, as access to digital archives has expanded, and funds for humanities research continue to dwindle, my own need to travel to archives has decreased substantially. Numerous libraries, archives, and museums have made large parts of their collections freely available online. Digitization initiatives provide greater access to these objects; at the same time they protect these fragile materials from frequent handling. Although I discuss the disadvantages of providing full, unfettered, and uncurated access to every archive in a recent Digital Humanities Quarterly article, when it comes to digital editions, and especially illustrated periodicals, I am grateful to have these digital texts within easy reach.

As my research has turned more and more to visual culture and illustration studies I have become increasingly dependent on digital libraries like HathiTrust, Internet Archive, and Google Books. Specifically, the improving resolution of the text scans in these repositories benefits my digital humanities work tremendously. In the past, for reasons relating to the cost of storage and hosting space, these PDFs tended to be low resolution, black and white, and often misaligned. The occasional archivist thumb even graced a few scans. Lately, accessing periodicals scanned in color, squared to the screen, with full OCR text recognition, and published at a high resolution has become, if not the norm, at least relatively common. I am grateful for these archives, and the partner libraries that provide access to their collections. The quality of these scans has been particularly valuable for a NINES indexed digital archive I direct called Visual Haggard.

Visual Haggard centralizes and improves access to the illustrations of Victorian novelist H. Rider Haggard. Recently, I have added PDF scans from Internet Archive to the site—an inclusion I was previously unwilling to make. This year I was grateful to add illustrations, including full-color covers, of several issues of Famous Fantastic Mysteries. This series published several serializations of Haggard’s fictions including a December 1945 issue of The Ancient Allan. Thanks to the generosity and community mindedness of the Pulp Magazine Archive within Internet Archive, I was able to save resources and improve Visual Haggard by adding relevant images to my digital humanities project.

—Kate Holterhoff, 3rd Year Brittain Fellow

Lloyd

“Can I work on the Furniss collection?” I asked.

Some might suggest I had no business requesting such a project, so distant from my own research: British novels during the long eighteenth century. But there I was, asking to work on a collection of film negatives by a relatively unknown Idahoan photographer taken between 1954 and 1995.

But I had a connection to Lloyd Furniss. He was not my family. He was not even my partner’s family. He was the grandfather of my partner’s brother’s wife. I knew his name only because my family ate dinner with Lloyd’s daughter, Peggy, nearly every Sunday during the early years of my PhD program.

“Of course,” the director replied, “if you want.”

Photograph by Lloyd S. Furniss, reproduced in the Idaho State Journal. Courtesy of Idaho State University Special Collections and Archives.

For the next two and a half years, I hunched like a scrivener at a desk for anywhere from two to 40 hours a week in the Eli M. Oboler Library’s Special Collections and Archives at Idaho State University, ignoring the ugly orange carpet beneath my feet as I pulled negatives from yellow paper envelopes, counting them and logging dates and descriptions in my Excel files. I presented on the collection and even collaborated on two exhibits featuring Lloyd’s photographs. The inventory count rose from one negative to a final tally of over 40,000.

One of Lloyd’s most striking photos captures a woman, nude, facing away from the camera, standing on a rise in the eastern Idaho backcountry. Her spine elongates, skyward arms form a Y, fingers pinch the corners of a wind-borne piece of tulle, which appears forever on the verge of letting float away.

Through pictures such as this one I learned to appreciate Lloyd’s passion for his work. I inventoried landscapes, animals, individual portraits, weddings, funerals, storefronts, social events, and bathing beauties. The apogee of his career, according to his son-in-law, Robert, was the opportunity to photograph Marilyn Monroe in Sun Valley, ID, on the film set of Bus Stop in 1956. Each image provided a different perspective, different content, but reiterated a similar theme: photography meant the world to Lloyd. I knew that as well as I came to know him.

My time in the Oboler archives taught me one of the costs of curiosity: uncertainty and risk. Yet curiosity can also lead us toward unanticipated rewards. I never had an endgame with the Furniss project because it was never about me and what I thought I could derive from it. This was personal. I succumbed to the impulse to know more about Lloyd, and as a result I experienced a level of familiarity with my research that I have rarely, if ever, experienced on any other project. We have probably all experienced the liberation of allowing expectations to fall away and finding what we were not searching for. In my experience, these epiphanic moments can renew resolve, instilling researchers with courage to let go again and again and again.

—Jeff Howard, 1st Year Brittain Fellow

Book Traces

Libraries were always a means to an end for me: they had books, I wanted books. My favorite day of the week when I was very young was “library day.” But I don’t remember the stacks or selecting the books. I remember walking out, my arms filled. The library itself was merely a repository. I still valued libraries, but I saw them as interchangeable. That was until I began to work in the Hayden Library at Arizona State University.

In 2016 under the guidance of Dr. Devoney Looser members and affiliates of the ASU Department of English began to search through the Hayden Library to contribute to the Book Traces project run by the University of Virginia. The goal of Book Traces is to record the evidences of past readers left in 19th and 20th century books, such as marginalia, scribbled notes, inserted letters, pressed flowers, and many other artifacts, in order to show the range of books’ individual material histories.

The process is intensive, dusty, and fun. I would take a few pages from a master-list of all the books in ASU’s collection published before 1923 in the PR and PS sections. Then I would search the stacks for PR4658.A1 1883 (Daniel Deronda), then PR4660.A1 1888 (Felix Holt, the radical), then PR4664.A1 1917 (Mill on the Foss), and so on. Once I found the book, I would briefly skim through it to find any traces. Most of the time there would be relatively little: underlining done by a 1970s undergraduate or an unintelligible gift inscription, “To JS from MS.” But as we searched we found remarkable artifacts.

Yes, @ASULibraries have a letter from (apparently) Derwent Coleridge in a novel by Sara Coleridge. A remarkable find!

— Kent Linthicum (@Kent_Linthicum) April 19, 2017

One of the traces I helped find was a tipped-in letter (which is to say the letter was bound or glued into the book) from Derwent Coleridge in Sara Coleridge’s Memoir and Letters (1873), both children of the famous Samuel Taylor Coleridge and likewise both famous in their own right in the 19th century. Some of our discoveries are viewable here: ASU Book Traces Project.

This project showed me how each individual library and individual book are significant. While the words might be the same between books, their readers were not. To this day I value going into stacks just to glance at the books to hopefully find a record, a bit of the past, for anyone to see.

—Kent Linthicum, 1st Year Brittain Fellow

Conversations Beyond Those We Hear

There are fingerprints in the dried black watercolor—fingerprints on a bear and its cub. The ledger drawing is old, the oldest paper I’ve ever touched. The stories in it are older, but I don’t know them and they’re not for me. Still, I am there, in a building built on the lands of the Kaw, Kansa, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, Osage, Pawnee, and Wichita.

There’s a conversation nearby, at the reference desk of the Kansas Historical Society Archives. One archivist tells the other, “Did I ever tell you that it turns out I have less Indian blood than I thought? My grandmother lied or didn’t know.”

“No! Really?”

Cheyenne Ledger Drawing possibly by Wild Hog, Indian History Coll. #590, Box 2 Folder 22, Kansas Historical Society Archives.

Another drawing. This one’s mounted on a cream-colored mat. It’d been on display at some point, they said. They kept it on the mat to keep it flat and safe. Its frayed corners are tucked into plastic tabs. I stare down at it, men and women and a tipi. Friends, family? A gathering? A memory? A ceremony? Again, I do not know.

It occurs to me that my fingers tracing along the edge of the page might be a ceremony, but I’m not sure. I’ve read Shawn Wilson: research is ceremony. Despite having read, I only vaguely know what ceremony is, but the grit on my fingers seems like it might be. That ceremony may not be not for me, but the grit remains on my fingertips.

I’m interrupted by a voice that comes over my shoulder. “Are you looking at ledger art?” It’s an older gentleman with a kind face. I explain that I’m doing research on the ledger drawings held at the archives. “Do you know the story behind these drawings? The Dodge City ledgers. Do you know what happened? The Cheyenne were attempting to go home.”

He sits, and we talk.

—Chelsea Murdock, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

On Meat and Unexpected Exchanges

Trips to the archive are inevitably accompanied by secret desires to find that certain something—be it a lost letter, an undiscovered manuscript, or even marginal handwritten notes—that will suddenly illuminate the previously unilluminated. It is these scribbles that keep any scholar coming back to the stacks.

But what keeps me interested is the everyday, even banal exchanges that accompany an archive—those items that are seemingly so meaningless as to be totally lost from memory if not for their place in a certain somebody’s archive.

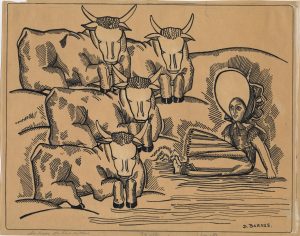

“Lhude Sing Cuccu!” (1930), drawing by Djuna Barnes. Courtesy of University of Maryland Special Collections.

The Djuna Barnes archive at the University of Maryland stands out as one such collection, in which you are likely to encounter the banal in every box. In January of 1973, Barnes wrote to a friend, “As of yesterday, I am sold to the University of Maryland.” The Hornbake Library’s expansive holdings indicate something of the tenor of Barnes’s “I am sold” statement. Amongst drafts of her wildly popular Nightwood, we encounter everyday items: train tickets, letters to doctors, passports, library cards, tax records, and sketches. Visitors get the distinct feeling that one day in January Barnes defiantly upended her junk drawer and shipped it off.

It is these items that help to bring the dead author to life.

There is no item more thoroughly indicative of Barnes’s personality than her exchanges with her editor at Faber and Faber and sometimes friend, T.S. Eliot. Their letters, even when seemingly trivial, indicate something of the oft-analyzed relationship between modernist women and the men who often acted as their editors.

While there are numerous lines regarding edits and resistance to edits, it is an everyday exchange regarding meat that—for me—is most indicative of their connection. From December 1951 to December 1952, Barnes’s letters outline her latest obsession—sending hefty cuts of beef. On December 26th, 1951 Eliot writes, “A very fine joint of beef arrived from Amsterdam just in time for Christmas; no name of sender given on the parcel, but it could have been no one but yourself.” And so begins a series of exchanges regarding slabs of red meat: a rump roast, a 7 pound rib roast, and even a few unsolicited packages that seem to have gone missing or rotted on the step. These peculiar exchanges are refreshing asides that reveal Barnes’ affection for Eliot, her persistence (in the case of unwanted packages), and the domestic aspects of their relationship. But so too do they speak of London in the early fifties. Post-war London experienced rations that would have made it highly unlikely for Eliot’s enjoyment of red meat had it not been for his “dearest Djuna.” Reflecting on the rationing of goods, Eliot writes in one such letter, “I am taking one of my few remaining pieces of full size pre-war paper for you, but don’t expect me to fill it.”

It is clear that despite their sometimes contentious relationship, Djuna Barnes and T.S. Eliot sustained one another in more ways than one.

—Maria Aldinger, 1st Year Brittain Fellow

Digital Marginalia

Marginalia in The Natural History of the Sperm Whale, 1839.

What is an archive? Often, we consider the archive a place where a researcher sifts through fragmented collections of items in a dimly lit basement of a library on a college campus. We imagine the smell of books and aging artifacts intermingled with pencil lead and white gloves—necessary for the preservation of the items chosen to represent histories of all sorts. The markers of the possibility of discovery within archival spaces seem to be findability and rarity. I am not an archivist, but my work questions how the digital archive could invoke the same romantic feelings as the physical archive.

My favorite example of a digital archive that provokes this same romanticism is Melville’s Marginalia. The site’s purpose is to reveal notes written in the margins of Melville’s books and, while the researcher will not hold the physical volumes in their hands, digital representation of Melville’s notes are now publicly available. Further, the archive preserves the same white glove feeling by including many photographed references. Moreover, the site provides different ways to browse the books that Melville kept in his library, for example, by clicking the image of a book or volume or by using the catalogue for a search similar to that of a library database. Now a researcher is not restricted to what is available at the Harvard Library, which is only a partial collection of Melville’s collection anyway, but can browse many titles in one space—the space of representation.

Dr. Steven Olsen-Smith, the initial archivist of Melville’s Marginalia, recognized the need for Melville’s research notes to be accessible for himself and other scholars. The availability of this information is no longer restricted and, therefore, continues the long celebrated concept of archives and libraries as spaces of information disbursement and equality. Just as the physical space of an archive can make a person feel like they are in a sacred place, the organization and design of the digital archive can produce the same effect of discovery.

—Amanda Girard, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

The Lesser-Known Flannery O’Connor

Libraries to me are second homes. From my first library card as a five-year-old at the San Jose Public Library to the protests I took part in this summer to save Macon’s Washington Memorial Library from funding cuts, libraries are an important part of my life. Though it’s hard to pick a favorite, I do have a special fondness for the Special Collections Reading Room at Georgia College’s Russell Library, where for the past four years I have spent weeks at a time diving deep into their collections.

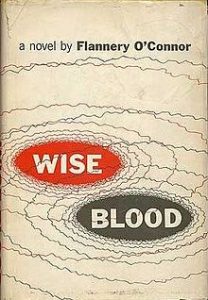

First edition cover of Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor, 1952.

I first visited there the summer of 2014 to do research in the Flannery O’Connor archive as a part of a month-long, NEH seminar with the theme of “Reconsidering Flannery O’Connor.” I spent a week in the archives then, reading through the manuscripts, letters, books from O’Connor’s private library, and other materials. Since then, that room has become another home for me: the big work tables; the collection of O’Connor souvenirs on the front table (tote bags, postcards, prints—I think I have them all now); the window into the front office, where I can often see Nancy Davis-Bray, one of my favorite people. Formally, she is the Associate Director for Special Collections there; informally, she is the bibliognost* of Georgia College’s Flanneriana.

My most rewarding experience there was reading the manuscript of O’Connor’s 1952 novel Wise Blood and discovering the early scenes cut from the final book, which not only revealed entirely new dimensions of O’Connor to me but also ultimately opened up an entirely new research project. Though not unknown to other scholars, these scenes were a revelation to me: O’Connor wrote multiple scenes which not only discussed but dramatized self-administered abortion. That the staunchly conservative and Catholic author wrote scenes in the 1940s in which a character not only talks about abortion but administers an abortifacient (and survives!) was astonishing. My fascination with these scenes set me on a path for my current project, on images of abortion in fiction of the pre-Roe era.

*Maybe that’s not really a word, but it should be.

—Monica Miller, Former Brittain Fellow, Assistant Professor of English at Middle Georgia State University

Freud’s Dogs

When it opened in 1963, the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library at Yale University was not universally beloved. Its distinctively modern architecture and gleaming marble cube-like façade was considered an eyesore amidst the Gothic splendor of the rest of Yale’s campus. It was called a “floating folly” and “white elephant,” among other epithets. The Beinecke’s director marked up souvenir postcards of the library by hand to point out supposed problems with its design shortly after the controversial building’s inauguration.

Viewed today, the Beinecke is less architecturally problematic than intellectually reassuring: it is one of the world’s largest repositories of rare books and manuscripts, with particular strengths in early modern manuscripts and American literature. A first-time visitor ventures inside the cube of the Beinecke’s upper floors via a revolving door to encounter the awe-inspiring sight of a glass tower of 180,000 volumes from the library’s collection; it’s something like the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, only made of old books and less sinister. The real action at the Beinecke, however, goes on in the subterranean reading rooms and storage facilities below the spectacle of the glass tower, where the majority of its million-plus volumes are housed and where researchers submit their requests for materials to librarians after having divested themselves of everything but laptops, pencils, and notebooks.

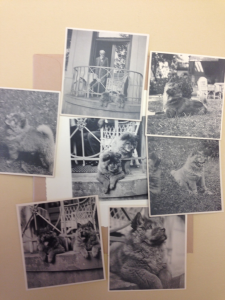

Pictures of Freud’s chows sent to H.D. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library.

I spent a week at the Beinecke in the summer of 2014 diving deep into its extensive collection of the manuscripts, letters, and ephemera of the modernist poet H.D. (1888-1961). Scholars have mined the exhaustive H.D. papers for years, and what they’ve found there has prompted a serious reevaluation of the trajectory of H.D.’s career and how to categorize her as a writer and artist—she wrote widely in a variety of genres (poetry, fiction, memoir, drama, spiritual writings), and much of what she wrote went unpublished in her lifetime. I was searching for more information about the time she spent being psychoanalyzed by Sigmund Freud in Vienna in the years immediately preceding World War II, as well as for more of the extraordinary writing she did in London during the War while surviving the Blitz. Other, luckier scholars had beat me to some of the really good stuff—like privately published poems circulated among friends and family as part of Christmas cards—but I spent hours poring over esoterica such as the poet’s horoscope book and handwritten notebooks she kept while recovering at a private Swiss hospital in the late 1950s. H.D. slowly and steadily gained volume, clarity, resolution, and texture the longer I stayed with her in the archives: she became less abstract and more a weighted, ineradicable, singular presence, despite how the jumble and sprawl of the archives emphasized her absence. I most remember touching the letters Freud sent her in London, how the stationery itself, the fonts it contained, conjured up lost worlds and vanished kingdoms of experience. Freud loved chows and sent H.D. pictures of them. These deeply specific, utterly everyday details, exchanged casually between two of the figures most responsible for the existence of modernism, were oddly illuminating, even moving; they cleared away cobwebs and flashed straight and clear in sudden moments. The mundane punctures the transcendent, true, but it’s also the only road available to it. Archives are the repositories where, as H.D. said, “possibly we will reach haven, heaven.”

—Jeff Fallis, 3rd Year Brittain Fellow

Reading Gaps in Georgia Tech’s Recipes

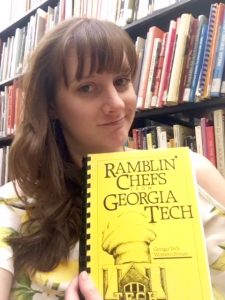

Dr. Darcy Mullen at the Kenan Research Center.

At the Atlanta History Center’s Kenan Research Center, I open Ramblin’ Chefs Georgia Tech. Complete with plastic comb binding, familiar to kitchens of the ‘80s, this community cookbook was compiled by the Georgia Tech Women’s Forum in 1985. It’s filled with the anticipated soup-can recipes familiar to fundraiser cookbooks. The contributors that are wives or the family of male faculty are identified through their husband’s names, too. It was hard for a woman to attend Georgia Tech, let alone teach here, and it’s interesting to note that 1985 is two years before the creation of the Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellowship, the faculty position I now hold at Georgia Tech. The administrative titles listed next to non-spouses reveal the gendered division of labor embedded in the cookbook. It’s clear what jobs these women don’t have.

Later, I tracked down the only other edition of the cookbook I could find: Buzzing Around the Kitchen, from 1997, which turns out to be largely the same text. The glaring lack of change leaves me with a dull feeling of a “you’ve come a long way baby” and “nevertheless she persisted” sandwich. These cookbooks are crystal-clear slices of time showing who was meant to do what in the institutional spaces I now occupy. In the “International Tastes” section there is “Hawaiian Sauerkraut Salad” (1997: 178), a recipe whose bland take on ethnic flavors reads more like assimilation, or racism. I wonder what America looked like from campus twenty years ago.

As a 30-something white woman, I am not surprised that a 30-year-old cookbook shows gender inequality. I am struck, however, that a cookbook made in the south would exclude southern food. For food rhetoricians, reading a cookbook is often an exercise in reading what isn’t there. These cookbooks are missing southern food. In doing so, they exclude Black culture. Michael Twitty connects the foundations of southern cooking with techniques and knowledge from African cooking. That lineage is absent in the world of these recipes. These recipes reflect a lack of Blackness in a very Black food space.

At the Kenan Center you can, and will, see history—and recipes—from an integrated collection of voices. It’s the kind of collection that allows one to understand why the gaps in these cookbooks matter. They leave out enough that they’re Schrödinger’s recipes—with Blackness both existing and not. As we mind the gaps, literary methodologies for reading what is there allow us to translate Toni Morrison’s “Africanist Presence” in recipes like “Kongo Squares” (1997: 126). Generously reading this gap of southern food (and therefore a history of African cooking) in these recipes could reveal how demographics of transplants map onto the kitchens of the south. We all know academia means moving. Or, it’s Occam’s razor. These mirrors do not reflect Blackness because that’s not the Atlanta these cookbooks could echo.

—Darcy Mullen, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Senses and Sensibility

Photo from Chawton House Library’s website. Pictured are Visiting Fellows from June 2015, working in the Upper Reading Room. Dr. Courtney Hoffman on the right, with the pink scarf.

I once purchased a bottle of whiskey for the description: “the scent of old books.” That tiny purveyor of fine spirits was just down the road from the Bodleian Library, two storefronts away from the coffee shop where, for £2.10, a double shot of espresso would cool enough to sip while walking between Brasenose and Exeter Colleges on the way to the Radcliffe Camera. Soreness, souvenir of hours spent in creaking wooden chairs; the slightest movement of paper while reading echoing under the Camera’s rotunda; the plunk from an occasional bit of dirt through the honeycomb ceiling in the Gladstone link, only air-conditioned study space with stacks; the silent paging though the first edition of Mary Hays’ Female Biography resting on inclined foam blocks in the rare books reading room: time in the Bodleian is sensual, slightly erotic in the way only a bibliophile appreciates.

Yet that whiskey and the scent of old books remind me, not of Oxford, but of Chawton House Library, outside of Alton in Hampshire. Surrounded by lush, green fields populated by surprisingly wily sheep, whose ability to escape the fence bordering the drive defied the ha-ha meant to keep them safely at a distance from the house, Chawton House holds a collection of texts to make any British Literature aficionado salivate. Volunteers restore damaged texts, and in the temperature-controlled archives, you’ll find books whose torn covers reveal newspapers and sheet music beneath the leather.

The musty, slightly acrid burn of that aroma particular to old paper and worn leather irritated my chest cold during the first half of the month I spent at Chawton. The centuries-old ceiling beams in my room (complete with four-poster bed) in the converted stables, where visitors can stay while studying, surely didn’t help. But nothing derailed my joy at reading first editions of Samuel Richardson’s Letters To and For Particular Friends and Frances Brooke’s The History of Emily Montague, a text I had not previously read and which subsequently influenced the direction of my research. Fresh produce from the garden, long walks across the fields, tea and scones with congenial company—my month at Chawton House Library evoked the best of my Austenite fantasies.

—Courtney Hoffman, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Archival Pedagogy

I’ve been involved with the University of Georgia’s Special Collection Libraries (SCL) in one form or another since shortly after their new building opened in 2012. I’ve taken my students, had a graduate class, researched, put together exhibits, attended symposia and other events, and spent time just walking around and exploring the galleries and exhibits—all at the SCL. I’ve seen and been introduced to so many fantastic objects in the special collections. For all intents and purposes, it’s been my archival home at UGA. But of all these scholarly opportunities, teaching in and with the archive has been one of the most rewarding experiences.

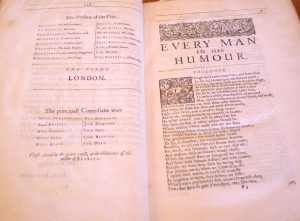

Title page of Every Man in His Humor from the 2nd edition of The Workes of Benjamin Jonson, one of the books my students looked at in the SCL. On the left, note that William Shakespeare originally acted in this play.

In the fall of 2017, 2015, and 2014, I taught a special section of English 1102 called Research Skills: Discovering the Hidden Treasures of UGA’s Special Collections. In my course, assignments centered around texts and other materials from the University of Georgia’s Special Collection Libraries. Early in the semester, we visited the SCL and worked with a librarian to develop students’ research skills. Many of them had never done research using primary sources, so they learned what is in the libraries’ collections, how to search for specific objects, and how to request materials to look at in the Reading Room. In these orientation sessions, the librarian also brought a few SCL objects so that the students could get some hands-on research experience. To a first-year student, a class built around library research might seem a bit daunting, but this introduction to special collections materials always captured the students’ attention and interest. Holding 400-year-old books whose covers were barely hanging on, reading the pocket-sized books of hymns that Civil War soldiers carried around with them, touching a book whose words were physically sewn over to create a new text, and trying to flip through a tiny book of psalms all connected the students to the past in a concrete way. They were being introduced to the idea that a book’s physical form is as important to study as its textual contents.

Mainly focusing on items in the SCL’s Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library collection, students took this new-found enthusiasm back to the classroom where they wrote about Civil War letters, elaborately constructed art books, a Babylonian clay tablet, first editions of classic books, a medieval choral gradual, and many other fascinating and unique objects. Of all the courses I’ve taught, this archives course is perhaps my favorite. In the research environment and among the materials available in an archive, students became more confident writers through primary research and were more invested in and enthusiastic about their assignment topics. Also, through their scholarship, I got to learn about so many more of the treasures waiting to be discovered in the stacks, or in an underground vault, in this case.

—Maria Chappell, 1st Year Brittain Fellow

Fortuitous Paleography

For books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them.

—John Milton, Aeropagitica

I can say that it was almost at the start of graduate school that I became passionate about archives. University at Buffalo has an excellent repository of early modern texts that includes Shakespeare’s First Folio as well as first editions of Paradise Lost and George Herbert’s The Temple, to name a few on a very long list. However, it was in 2011 during a year-long seminar, “Researching the Archive,” that I fell in love with archival research and reading old manuscripts from the 16th and 17th century. The Folger Institute’s seminar brought together graduate students from across the country with leading scholars, Nigel Smith and Peter Lake. There in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s reading room the ten or twelve of us would sit with other scholars and read from old texts for hours. One of my colleagues, Dr. Colleen Kennedy, whose work was on Shakespeare’s sensorium, would pull from the repository absolutely fascinating material. Old books are cool, but old scratch and sniff books with pullout pages that span six to eight feet are constitutionally awesome!

The Folger Institute at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

After I graduated, I stayed in close contact with the Folger Institute by attending faculty seminars and research visits during semester breaks and summer vacations. In 2016, I took Dr. Heather Wolfe’s “Introduction to Paleography.” It was during this seminar that the archive and the study of paleography came to life. While preparing for an estate sale, a family in the United Kingdom found a manuscript written in secretary hand. And, as luck would have it, the family reached out to a seminar participant or Dr. Wolfe (my memory is a bit cloudy on who was the person of contact) to help sort things with the manuscript. We corresponded and chatted with the owners of the estate and manuscript to help transcribe and date the document. Our studies all week had culminated in a sort of manuscript who-done-it mystery. In that moment, I caught the archival bug. I do not have any plan for arranging a course of treatment for that malady other than future trips to the archive to read and learn amongst the stacks.

—Joseph Aldinger, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Weird Magic

During my career in academia, much joy and most of my modest accomplishments came through archival research. In the Fall of 2006 I took an American Studies course during graduate school. Ammiel Alcalay, our professor (who almost always arrived for class with bags of books and papers from his own personal archive), exhorted every one of us to explore relevant archival holdings wherever they could be found: to read letters and notes; find out-of-print books; revisit first editions; and, most of all, if possible, unearth never-published documents. Ammiel’s encouragement gave us a sense of permission but also a larger sense of mission: to complicate and enrich the field of American Studies through archival research.

My own particular field was American poetry, so I nervously ventured into The New York Public Library’s Berg Collection of English and American Literature to spend time with Lorine Niedecker’s handwritten book of poems from 1964, Homemade Poems. The poems themselves and the exact, careful way Niedecker had inscribed them—one per page with plenty of enveloping white space—became central to my in-process dissertation on “small poems,” and I later had the opportunity to serve as the editor of a facsimile edition of Niedecker’s handmade book. (I won’t say any more here about the project, since there is already a wonderful, hyperlink-laden TechStyle post about it.)

From George Oppen’s Daybook materials. Courtesy of UC San Diego Archive for New Poetry.

A few years later, with the help of a research grant, I traveled to UC San Diego’s Archive for New Poetry in order to spend time with poet George Oppen’s papers, specifically his complex, famously disheveled “Daybooks” made up of stacks of papers—typed as well as handwritten on diverse sheets and scraps—that were bound by things as unconventional as nails or pipe cleaners. I traveled across the continent for a chance to work with the Oppen papers even though the Daybook materials themselves were only available via microfilm, and therefore physically off-limits to me, owing to their fragility. As I wrote in my notes at the time, “Of course this is not equivalent to engaging with original documents, though I do think microfilm’s weird magic makes it superior to digitized images in certain ways.” Even the mediated experience of the archive was powerful, but it also stirred up the conviction that some non-transferrable value, this weird magic, inheres in handling physical materials and documents: “Such enchantment and such pleasures of control are fine, I guess, as far as they go, but one wants and needs also (not necessarily only) to hold the leaves, spines, sheets, slips, fascicles in question; to see how the different inks and colors and markings play off each other; to determine or at least have better guesses about what words a scribbled phrase really consists in; and withal to find oneself in the place of the writer, physically oriented to some given page-space and tangible material just as the handler-inscriber of said materials might have been.”

To locate the notes and documents I needed for this piece, in particular the precious folder of Daybook printouts, I had to spend several hours in one of the closets in our home, working through stacks and stacks of disordered boxes that contained everything from ancient high school binders to birthday cards and obsessively annotated academic articles. I am much more of a packrat than an archivist myself, but I do love archives, and I believe in them, especially their messier handwritten, piled, annotated, fragmentary, ephemeral fringes. Saving and spending time with such “small” materials—either through direct handling or by means of microfilm or the web—is an untidy business that matters, and not just for scholars and librarians. Archives of any kind are vital records of how people externalize, process, and preserve their thoughts and their lives, and I hope we will continue to turn our attention there.

—John Harkey, Former Brittain Fellow, English Teacher at Brookstone School

Murder in Paradise

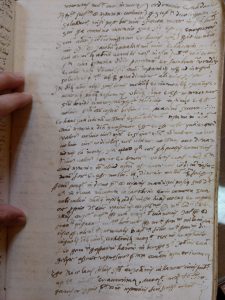

Signore Carlo Thieri’s notarial chicken scratch. Courtesy of Archivio di Stato.

In his 1555 last will and testament, Signore Carlo Thieri threatened to disinherit his three sons if they murdered someone. I learned that this morning while struggling to decipher the really bad Latin and chicken scratch handwriting of notary Giovanni Villanova. I found similar threats in the 1547 wills of Alberto Fontana and his wife, Diamante, except that their son Jacopo had already helped murder someone, so it was probably too late for their threats. And I had to stop myself from laughing out loud when I read a letter from the ducal governor of Modena, who after reporting on the 27th homicide or attempted homicide in the past two months, pointed out that maybe these rather violent nobles shouldn’t be allowed to have weapons. I’ve gone through at least 100,000 documents (at least), pieces of paper and parchment over four-hundred years-old, following the trail of murder and revenge to be able to tell you this.

Historians often have their home archive. Since I climbed the marble staircase my first year as a History PhD student, the Archivio di Stato in Modena, Italy has been that home. It sits on the site of an old Dominican convent and monastic bells ring from somewhere I’ve never been able to figure out. The reading room contains some really bad frescoes of Napoleon who supervises us as we leaf through the sheaves of materials on wooden tables. The windows overlook the former monastic courtyard and right now the persimmon tree outside the east window is heavy with fruit. The documentary supply feels endless—so many chances for serendipitous discovery. I’ve been going back for over a decade now and I still see the same faces, except the man who looked like a frowny Mr. Rogers who ate a banana every morning. I could keep telling giving you facts but there are no facts for why I love this archive nor is this an argument I could make for it. If this sounds like a love letter, it’s because it is. Borges said that he always imagined paradise as a library—mine is this archive.

—Amanda Madden, Former Brittain Fellow, Research Scientist at Georgia Tech’s Center for 21st Century Universities