Imagine a bay. The word “bay” may conjure up scenic images of calm, turquoise blue waters, of expansive coastal sand dunes, or of bustling marinas. The imagined landscape, unsurprisingly, may vary widely from one person to another. And yet, whenever I assign my students to read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s essay “Learning the Grammar of Animacy,” many are baffled by Kimmerer’s reflections on the word:

When “bay” is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But wiikegama, to be a bay, the verb releases the water from bondage and lets it live. “To be a bay” holds the wonder that, for this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers. Because it could do otherwise—become a stream or an ocean or a waterfall—and there are verbs for that, too. (173)

Kimmerer, a plant ecologist and enrolled member of the Potawatomi, laments the limitations of the English language. Unlike many of the indigenous languages of the Americas, nounbased languages such as English fail to express what she calls the “animacy of the world.” For her, it is the prevalence of verbs in the Potawatomi language that allows for water, rocks, and mountains to become alive. The notion of the natural environment as a sentient, living being makes many of my students examine cultural biases that are subtly embedded in their native language(s). The angle of vision that the tribal language affords enhances their awareness of the relationship between the world they inhabit and the words they use to describe it. However, not everyone in the classroom is in agreement with Kimmerer’s stance. The English language may be less verb centered than tribal languages, some students have argued, but that does not diminish its ability to articulate a particular idea. It may just take more words to capture the idea or a new word altogether. For instance, one might choose to abandon the term bay in favor of bayness, a word that more closely approximates the intended meaning. No matter the outcome, Kimmerer’s text sparks class discussions that shed light on the flexibility of languages—their ability to accommodate new meanings and perspectives—as well as on the process of translating from one language into another.

The attempt to build bridges across languages and cultures was at the center of the World Englishes Committee’s 2013-14 major event “Reframing Multilingualism in the Classroom: A Poetic Celebration of Diversity.” The event featured international Georgia Tech students reading poetry from their home countries in the original language and in English as well as faculty presenting pedagogies related to multilingualism in the classroom. Turning linguistic and cultural diversity into a resource for learning and personal development, the event showcased the many different ways in which international students allow both their peers and instructors a glimpse into region-specific festivals, foods, landscapes, and a multitude of worldviews and philosophical beliefs.

The opening remarks by S. Gordon Moore, Jr., Executive Director for Student Diversity and Inclusion at Georgia Tech, set the stage for an event that fostered awareness of Georgia Tech’s culturally, ethnically, and linguistically diverse campus and that addressed the value and pitfalls of translation. Moore stressed how principles of diversity and inclusion have been widely embraced in all areas of campus life and pointed to poetry as a common language capable of transcending race, class, and gender boundaries. Moore put particular emphasis on effective communication as key to successful relationships and reminded us of the limitations of automated translation tools.

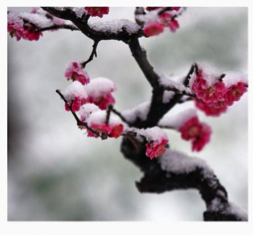

The highlight of the event was the poetry recital by Georgia Tech students Jose Andres Rodriguez, a sophomore majoring in Aerospace Engineering and originally from Caracas, Venezuela; Ali Syed, a freshman majoring in Mechanical Engineering and originally from Lahore, Pakistan; and Xueying Zhao, a senior majoring in Materials Science and Engineering and originally from Shanghai, China. Jose, Ali, and Xueying each read a poem of their choice and shared their thoughts on the differences between original and translated versions. Jose chose to read “Orinoco” by Venezuelan poet Aquiles Nazoa. He was drawn to this particular poem because it describes one of Venezuela’s most extraordinary geographical features: the Orinoco River. Jose was intrigued by the natural and cultural history associated with a river that is dominated by magnificent coastal mangrove forests and home to various indigenous tribes. Unable to find an English translation of the poem, Jose decided to undertake the translation himself. Necessity turned into a rewarding experience: Faced with the challenge of bringing the poem alive to an English-speaking audience, he noticed the limitations of a word-for-word translation and tried capturing the context, tone, and mood of the poem as a whole. Ali’s recital of Punjabi poet Bulleh Shah’s “Enough of Learning, My Friend” shifted attention to the emotional resonance of poetry. Filled with allusions to mystical experience and spiritual insight, Shah’s poem inspired Ali to rethink his approach to learning and to turn inwards for answers whenever reflecting upon his life. Deeply moved by the original version of the poem, Ali noted the loss of implicit cultural information that reflects particular social norms, religious beliefs, and ideological attitudes in its translation. He noticed how images and expressions in the English language may match the meaning of the message yet fail to capture the emotional import of the original. Xueying, in turn, commented on qualities both lost and gained in the English translation of a poem written by Li Qingzhao, a poetess in the Song Dynasty of China, and entitled “Pride of Fishermen.” Written during the poetess’s younger, more carefree, days, the poem spoke to Xueying because of its elegance and symbolic richness. She was intrigued by the metaphoric relationship between the poem’s central image—a plum blossom which stands for perseverance and purity in Chinese thought—and the poetess herself. While its spiritual dimension recedes into the background in the English version, the poem here takes on a materiality and concreteness no less compelling.

Poster designed by Georgia Tech students Grace Halverson, Rachael Ragan, Haley Ricks, and Xialin Yan.

The presentations by faculty members Jonathan Kotchian, Jennifer Lux, Malavika Shetty, and myself on how to integrate international students’ diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds into our teaching concluded the event. Kotchian demonstrated the value of unconventional methods, such as asking students to recite Shakespeare without using their tongue, in both highlighting nonverbal elements as powerful communicative tools and “leveling the playing field,” as he put it. Lux showed how different visual presentations of a literary text harbor significant, and often surprising, clues into culturally specific cognitive frameworks. Shetty urged us to take a multilingual approach to composition that allows non-native speakers of English to bring in their methods of argument in rhetorically strategic ways. My own presentation focused on the integration of a communication model where Western and indigenous multimodal textualities enjoy equal status and where students are encouraged to move between them in contextually relevant ways.

Poster designed by Georgia Tech students Grace Halverson, Rachael Ragan, Haley Ricks, and Xialin Yan.

Because sound plays an integral part in transmitting the meaning of a poem, the student performances beautifully showcased the value of both multilingual and multimodal literacies. The speakers’ personal engagement when reading the poems demonstrated how cultural identity is anchored in an individual’s specific experiences and turned abstract words on the page into concrete sensory impressions such as tone, mood, and emotional flavor. Precisely the shift to the senses made the poems personally meaningful and helped audience members relate to and empathize with what was being said. Enhanced by a willingness to listen and a desire to understand, translation occurred across both linguistic and cultural boundaries. Even in its imperfect transferal of semantic content, it deepened awareness of the epistemological otherness that inhabits languages and the world at large and fostered cross-cultural exchange and understanding. Insofar as the bilingual recital led the student speakers themselves to adopt a critical detachment from the original text and to look at it from a new perspective, the event allowed for a creative negotiation of difference on the part of performers and audience members alike.

Excerpt taken from “Orinoco” by Aquiles Nazoa (1920-1976)

Poem retrieved from poesadaada.blogspot.com

Reader and Translator: Jose Andres Rodriguez

Tú mismo

te empinaste hacia abajo,

esotérico,

con un hondo respeto de la tierra

y diste a tus mil brazos

aptitud atlética

para recibir la crianza del trasatlántico,

para prenderte a las orillas

grandes ciudades que te caen

como tributarios de vida,

para ser el zaguán del mar,

traficado por los gritos de la tierra

que se echa a las calles del mundo.

Denso, populoso,

te caen y se te ahogan

duras palabras engranadas

en todos los idiomas del planeta.

Pero, todavía,

fuerte Orinoco,

todavía eres el Río Indio,

inconfundible,

en el salto,

en la bandada,

en la garza en un pie, que casi vuela

y en tu último caiman

en cuyo bostezo

se refugió toda tu tradición

con silenciosa desembocadura.

___

You yourself

chose to go downslope,

esoteric,

with a deep respect toward land

and gave your thousand arms

athletic aptitude

to receive the breeding of the Atlantic,

to allow in your shores

flourishing great cities

as life proofs,

to be the hallway of the sea,

navigated by the uproar of the land

that takes the streets of the world.

Dense, populous,

you receive and drown

tough words written

in every language.

But yet,

mighty Orinoco,

you are still the Indian River,

distinct,

in its waterfall,

in the flock,

in the heron standing on one foot that almost flies

and in your last crocodile

in whose yawn

took shelter your entire tradition

with your silent mouth.

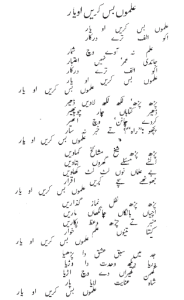

“Enough of Learning, My Friend” by Bulleh Shah (1680-1757)

Poem retrieved from apnaorg.com

Reader: Ali Syed

___

Enough of learning, my friend!

Enough of learning, my friend!

An alphabet should do for you

To it there is never an end

An alphabet should do for you

It’s enough to help you fend.

Enough of learning, my friend!

Enough of learning, my friend!

You’ve amassed much learning around

The Quran and its commentaries profound

There is darkness amidst lighted ground

Without the guide you remain unsound

Enough of learning, my friend!

Learning makes you Sheikh or his minion

And thus you create problem trillion

You exploit others who know not what

Misleading them with wild opinion

Enough of learning, my friend!

You meditate and you say your prayers

You go and shout at the top of the stairs

You cry reaching the high skies

It’s your avarice which ever belies

Enough of learning, my friend!

The day I learnt love’s lesson

I plunged into the river of divine passion

An overwhelming gale. I was confused and lost

When Shah Inayat cruised me across

Enough of learning, my friend!

“Pride of Fishermen” by Li Qingzhao (1084-1150s)

Poem retrieved from wapbaike.baidu.com

Reader: Xueying Zhao

渔家傲

雪里已知春信至,

寒梅点缀琼枝腻,

香脸半开娇旖旎,

当庭际,

玉人浴出新妆洗。

造化可能偏有意,

故教明月玲珑地。

共赏金尊沉绿蚁,

莫辞醉,

此花不与群花比。

___

Pride of Fishermen

Herald of spring in winter snow, plum flower

O you adorn the branches with rosy hue

Of your half-open petals, like the profiled face

So full of grace

Of a sweet bathing beauty in attire so new

You find a special favor in Creator’s eye

The moon caresses you with pure beams from on high

Golden wine cup in hand let us enjoy the fair

And not declare that we’re drunk

for her beauty is beyond compare.

The World Englishes Committee creates resources and organizes events that promote cross-cultural perspectives about research and pedagogy in multilingual education. In particular, it assists faculty in developing innovative teaching methods that incorporate the diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds of international Georgia Tech students, fosters their visibility and confidence, and celebrates multilingualism as a culturally enriching experience. By both affirming rhetorical plurality and recognizing discursive constructions of cultural dichotomies, the committee strives to build bridges between words and worlds.

About the Author: Mirja Lobnik (PhD, Comparative Literature, Emory University) has been a Brittain Fellow since 2012. Taking a global approach to the study of the Americas, her research and teaching focus on storytelling traditions in the context of multi-ethnic American, Caribbean, and South Asian literatures. Inspired by ecophilosophy and new materialism, she investigates acoustic ecologies in order to illuminate the connections between embodied experience, culture, and the natural environment. Her current book project is an interdisciplinary study arguing for the relevance of ecocritical perspectives to contemporary thinking about sound as a cultural, environmental, and artistic medium. A preliminary version of the first chapter is forthcoming in Modern Fiction Studies.