Nola Darling’s “My Name Isn’t” anti-harassment street campaign from the Netflix series She’s Gotta Have It provided inspiration for this assignment (as well as Netflix’s social media campaign #MyNameIsnt). Netflix, 2017.

Introduction

While the senseless deaths of Black men have gained national attention, Black women are often excluded in the national debate concerning this topical issue of state violence. There is minimal coverage in the mainstream media of Black women’s bodies, and often the maltreatment of Black women by police goes unnoticed. For example, women like Sandra Bland, Rekia Boyd, and more recently Breonna Taylor have largely been left out of this “new” reckoning of police brutality, racial injustice, and systemic oppression. [i]

My English 1102 course during the Spring Semester 2020, “Narratives of Black Girlhood,” responded to this unsettling trend as it underscored the importance of representation, visibility, and empathy of others’ experiences of the world. I decided to use African American literary texts as entry points for students to examine varied portrayals of how Black girls negotiate space both publicly and socially. [ii] Though my own research focuses in particular on Black women’s experiences of survival and engages how Black women are read in different spaces, I wanted my students to think about the next generation of daughters and study the lived experiences of Black girls through the lens of Black women writers. In particular, I wanted them to consider how these writers compose uniquely authentic and affirmative narratives that seek to oppose stereotypical depictions of Black girls and (re)center Black girls’ voices. Within our ongoing discussion, students revisited these key questions throughout the semester:

- How do media representations of Black girlhood impact the ways Black girls live at the intersection of race, class, and gender and negotiate multiple identities?

- How do Black girls revise, resist, or reject traditional notions of femininity, as well as societal perceptions of Black girlhood?

- How do Black girls, through the influence of Black women around them, make meaning of their lives and shape their social and political futures?

- What role does literature (especially these authentic and affirmative narratives) play in opposing stereotypical depictions of Black girls and (re)centering Black girls’ voices?

Inspirations for Re-Seeing Black Girls Poster Project

Inspired by Nola Darling’s “My Name Is Not” street campaign in the 2017 Netflix series She’s Gotta Have It, I wanted to create an assignment for which students would use visual rhetoric to call attention to how Black girls grapple with visibility and validation. [iii] Ultimately, students were prompted to design a poster that sought to counter how Black girlhood is negatively constructed and in turn, re-see Black girls as more nuanced, complex individuals. The assignment had two options. For either option, the students’ main objectives involved the use of visual rhetoric to create awareness of social biases regarding Black girls and demonstrate empathic understanding of their perspectives.

Option One

“Design a poster that challenges/counters one prevailing stereotype of Black girls and seeks to create more dynamic, complex representations of Black girlhood. In this option, you should counter how Black girlhood is negatively constructed. In your design, consider the ways in which you will re-see Black girls by visually challenging a prevailing stereotype projected onto Black girls that is reflective in your culture. How you define “your culture” is up to you. You might design a poster that challenges misrepresentations of Black girlhood reflective in 2020 American culture, at Georgia Tech, or youth culture’s relationships with established institutions.”

Option Two

“Design a poster that captures a detailed portrait of LaTasha Baxter or Octavia “Sweet Pea” Harrison of Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones. In this option, you should engage how Black girlhood is constructed in African American literature by zeroing in on LaTasha or Octavia’s trajectory and visually dissecting her experience. Your portrait should go beyond the mere description that Jones gives us from the novel and get to the essence of the individual: What is it that makes your subject complex and dynamic? In your design, consider the ways in which you will re-see Black girls: How will you capture the subject’s essence? How is she significant (to thinking about the Atlanta Child Murders, course inquiry, etc.)?”

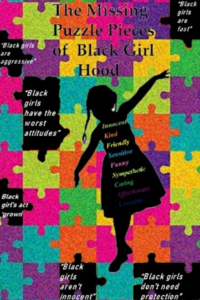

“The Missing Puzzle Pieces of Black Girlhood” by Apueela Wekulom

In the example to the left, Apueela Wekulom’s composition, a response to option one, presents an astute aesthetic of puzzle pieces to show how stereotypical depictions impact how Black girls move. In her artist statement, Apueela observes that it is “sort of a balancing act between being a child yet viewed as an adult” and reveals that “the young girl gets around these stereotypes by avoiding the obstacles that society pushes on her. She teeters to one side as she tries to avoid the gaps in the puzzle pieces. The young girl is placed in the middle intentionally in order to emphasize her position in the world and draw attention to her struggle.” By capturing the lived experiences of Black girls as a “balancing act” in her poster, Apueela prompts her viewers to think about the ways in which Black girls’ movements are severely circumscribed, and illustrates simultaneously how Black girls adjust and adapt to negotiate the spaces they occupy both publicly and socially.

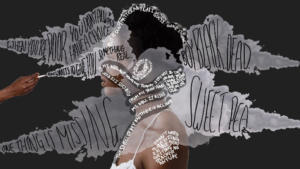

“Her Smoke Rises from My Skin” by Julia Chen

Another student, Julia Chen, chose option two where she visually dissects Octavia’s experience by using the smoke clouds as a metaphor to capture her movement as a Black girl. Julia writes, “Even with the chaos of the smoke and words surrounding her, the profile of the girl in the middle is still standing tall, which is the aspect of Octavia that I wanted to shine through the most. The main idea of the poster is that Octavia is like a phoenix, her mother’s words rising from her skin, while she herself is rising from the ashes of the fires that burn around her.” By adroitly incorporating passages from Leaving Atlanta to reveal Octavia’s complexities and capture her essence, Julia skillfully achieves the goal of eliciting empathic understanding of others’ perspectives.

Why Visual Rhetoric?

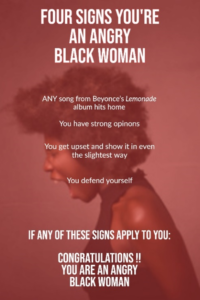

“Four Signs You’re an Angry Black Woman” by Jordine Jones

I chose visual rhetoric as a key component of this project assignment because I wanted to emphasize in this unit that representation matters. The course inquiry aforementioned prompted students to recognize the significant role Black women writers play in challenging stereotypical depictions of Black girls, and most importantly (re)centering their voices as complex individuals. Through visual rhetoric, students found concrete ways to make Black girls’ experiences visible and, in turn, redefine what Black girlhood entails apart from stereotypical definitions. While the students’ artist statements accompanied with each poster translates what is made visible in their compositions, images do what words cannot. The students’ compositions, in turn, function as a portal through which varied audiences can perhaps make the shift to change the distorted narratives of Black girlhood.

I encouraged the students to deconstruct binaries when challenging stereotypical media tropes. During in-class discussion, we considered how anger is translated onto Black women and girls’ bodies and discussed how students might address the Black woman stereotype in their posters. Students learned that merely including a subject smiling without exploring the nuances is counterproductive as it minimizes anger as a healthy emotion and diminishes or dismisses Black women’s right to rage. [iv] In this poster to the right, Jordine Jones considers how anger is managed and written on Black women’s bodies, and subverts these implications to reveal commonalities society often ignores. Inspired by Beyoncé’s album Lemonade, Jordine’s composition dispels the myth of the angry Black woman by listing emotional reactions that are shared across cultures. [v] In turn, her aim is to convince her viewers to shift their perspectives and recognize the logical fallacy of stereotyping Black women as angry.

“Pointing Fingers” by Emma Gratton

A few students also responded to a popularized example of tennis star Serena Williams being harshly judged by the media for her “lack of decorum” after losing the US Open. In their posters, they call attention to how Black women and girls are assigned punishments and often policed for their emotions.

By alluding to the incident, Emma Gratton’s composition makes great use of emphasis to quickly convey and validate Black girls’ right to be angry: “I want to challenge people’s confirmation biases by providing counter examples to the commonly held stereotype of the angry black girl [via a rhetorical question].”[vi] Emma’s strategic use of rhetorical questioning prompts viewers to not only reflect, but also shift their ideologies.

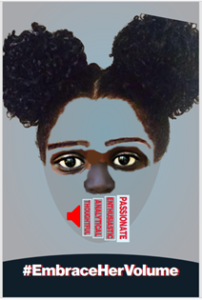

“Embrace Her Volume” by Ana Herrera

Similarly, another student, Ana Herrera, challenges societal perceptions of what it means to be loud: “I want to promote inclusivity by inviting my audience to embrace and respect all the different volume levels. The words on the volume level marker are meant to be better alternatives to refer to different volumes of speaking as opposed to ‘loud’ or ‘noisy.’ [These terms] are present as a reminder that there is a lot of diversity regarding volume, [and reinforce] the idea that no person should be boxed or ‘stereotyped’ into any of them.” By incorporating a hashtag in her design, Ana achieves her objective of creating awareness about social biases among fellow Generation Z consumers.

Additionally, visual rhetoric gives students a platform to create awareness about social biases and provides them with a charge to shift how the media recapitulate stories of Black girls that “we” often subscribe to. For example, Miranda Leggett’s composition uses abstract art to reveal how “societal filters” impact Black girls’ movement, and particularly reflects on Octavia’s trajectory in Leaving Atlanta. In her artist statement, Miranda states,

“Filtering for Perfection” by Miranda Leggett

“There are some filters that girls are aware of as Octavia is aware of how her dark skin results in her being called ‘Watusi’ (she recognizes it, but also chooses to reject it and does not let it bother her) and…[b]eing poor is a filter that she … actively tries to ward off. These two are examples of filters that Octavia is aware of, and so they are green, to signify that they will grow along with her. But, as in real life, a young girl cannot see all of society’s filters. The white triangle that sits behind her photo signifies some sort of filter that has not been placed on her yet but might be in the future. The fact that it is white also mirrors the idea that the filters placed on her as she grows will likely be placed on her by white people.”

In her design choices, Miranda compels her viewers to consider how societal filters particularly impact how Black girls live at the intersection of race, class, and gender.

Conclusion

How we are seen in the world impacts our movement. How the media constructs the lived experiences of Black girls matters, because media representations help shape our mythologies. With this assignment, my students discovered that stereotypes, positive or negative, can be damaging and limiting, and they used visual rhetoric to arrive at more nuanced definitions of Black girls’ movement. This assignment created an opportunity for students to consider the ways in which we can deconstruct binary thinking and practice antiracism daily.

Ultimately, representation broadens our understanding and appreciation of differences. As the only Black woman in my cohort of postdoctoral fellows, I have experienced isolation and alienation in ways that are hard to articulate. It is not what people are doing to me; it is more so how people respond in subtle ways to my presence/visible difference in a room. These subtleties can still create an uncomfortable space for people of color as I, too, am very cognizant of how I move professionally and personally as a Black woman. This project assignment sought to normalize how Black women and girls move through space by calling attention to the racist tropes that seek to undercut Black girls’ and women’s experiences of survival. Many of my movements as a Black woman are redolent in my students’ compositions; this project’s relevance is even more paramount and palpable considering this summer’s recent reckoning with systemic racism, police brutality, and white supremacy. [vii] When we prompt students to challenge normative standards that imply that certain differences are undesirable, we make space for others’ experiences.

In all, it is my hope that more academics seize the moment to equip students with the tools to lean into their discomforts and have meaningful discussions about representation, visibility, and power imbalances. It is also my hope that by underscoring marginalized perspectives in the classroom, students will recognize and discover that differences matter as they reveal our complexities and uniqueness. More comprehensively, expanding our lens is key to creating inclusive communities.

Virtual Gallery Walk: You may browse other student compositions accompanied with excerpts of their artist statements.

[i] I place “new” in quotation marks to indicate the ironies around the fact that this conversation is not new, but is the story of America: as Ta-Nehisi Coates points out, “white America’s progress … was built on looting and violence” (6). Of note, many people have rallied behind and initiated efforts to seek justice for Breonna Taylor, although these efforts have been mostly futile. Most recently, the grand jury decided to indict one of the three police officers on “wanton endangerment” of Taylor’s neighbors’ homes, leaving many speechless as to why this charge didn’t apply to Taylor.

[ii] I wanted to create a range of diverse narratives and worldviews for students to come to understand in their exploration the ways in which Black girlhood is constructed and represented across cultural, social, and political constructs in African American literature. In these readings, it is my hope that students recognized commonalities, but also noticed key differences that dispel mythologies that Black girlhood is monolithic. I chose Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (1976) by Mildred D. Taylor, a work of historical fiction; Leaving Atlanta (2002) by Tayari Jones, a novel set in Atlanta; and The Hate U Give (2017), a contemporary-based novel.

[iii] She’s Gotta Have It (2017) is an adaptation of Spike Lee’s first movie by the same name, which follows the life of a Brooklyn artist Nola Darling, who juggles her life as an artist and her relationships with her friends, family, and three lovers. The street campaign aforementioned enters the conversation around street harassment and boldly calls attention to the ways in which women are harassed while walking by via comments of sexual nature.

[iv] In her most recent book, Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Brittney Cooper considers how Black women can reclaim their right to rage to not only dispel mythologies regarding their identities but also to challenge interlocking systems of oppression.

[v] Jordine observes in her artist statement that Beyoncé’s album Lemonade parallels the “course theme of empowering and recentering Black women and girls’ voices.” In particular, she points out that the song “Hold Up” especially upholds aggression and anger as acceptable emotions for coping with a partner’s infidelity. Further what is more revealing is that the emotional responses voiced in the song are reminiscent of the four stages of grief, general patterns and reactions shared across cultures.

[vi] Earlier in her artist statement, Gratton describes confirmation bias as follows: “when people see an action that aligns with something they believe, they add that incident to their memory to further convince themselves that they are right in what they believe even if it is incorrect.”

[vii] The blatant murder of George Floyd, captured by a bystander for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, is indelibly etched in the minds of people around the world, sparking global protests against police brutality. During this summer, people protested not only for Floyd, but also for many others who died at the hands of police this year, which include Ahmad Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and Jacob Blake.

Works Cited

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. Spiegel & Grau, 2015.

Cooper, Brittney. Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower. St, Martin’s Press, 2018.

Jones, Tayari. Leaving Atlanta. Warner Publishing Grand Central Publishing, 2002.