Screenshot from an episode of the TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Most of my students did not like poetry. I don’t remember what prompted the realization—probably something banal like analyzing a poem by Dickinson, Keats, or Frost—but I remember the crushing sensation of disappointment and dismay, even despair, that settled over me. Many of them actively disliked it, a few of them copped to hating it. They didn’t understand poetry; they saw it as difficult and purposeless, the forbidding literary equivalent of calculus. It was early in my teaching career, and as an eager graduate instructor I tried valiantly, then defiantly, then defeatedly, to share my deep-set and at times inexplicable-even-to-me enthusiasm about poems with my students, but rarely did it seem to take. After a few more semesters of effort and rebuff, I gave up trying, especially in freshman composition courses. I internalized my students’ allergy to poetry and assigned the minimum amount necessary to meet course requirements, my true feelings about the genre dampened and locked away for fear of embarrassment, rejection, and frustration.

Obviously, as a poet myself, this sort of situation was untenable. When I arrived at Georgia Tech as a Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow in the fall of 2016, an unusual opportunity presented itself: I was the recipient of a new Pedagogy Grant in association with the long-established Poetry@Tech program and reading series. The purpose of the grant was to further “embed” poetry in Tech classrooms. This poetry requirement fit awkwardly into the first course I taught at the Institute, but less so into later courses where I made more considered allowances for it. My students read poems related to class concepts such as utopias and dystopias, attended Poetry@Tech readings and wrote responses about how oral, nonverbal, and written modalities collided at those readings, and even went so far as to try writing poems in Orwell’s Newspeak from 1984. (See my previous TECHStyle contribution “The Doubleplusgoodspeak of Newspeak: Poetry and Orwell’s 1984” for more detail on the latter, terrifying exercise.) Poetry began to creep back in from the margins and become a meaningful pedagogical tool.

Cover of The Hatred of Poetry.

It’s perhaps unsurprising then that when I read Ben Lerner’s newly published book-length essay The Hatred of Poetry (2016), I wasn’t enthusiastic about it. I did appreciate how provocatively and straightforwardly the book presented its central thesis: the reason poetry is universally hated, by both writers and readers, is that the genre offers up the promise of an ideal form of communication (timeless, universal, intimate, irreducible) that is rarely fulfilled by actual poems. Imperfect individual poems fail to embody or enact what Lerner calls “the utopian ideal of Poetry” (76), and everybody is left frustrated and unsatisfied as a result. I’d been thinking a lot about Lerner’s books and ideas, and talked at length about Lerner’s work with former Brittain Fellow Andrew Marzoni on Episode 19 of The Office Hour podcast. But there was still more I needed to process. The Hatred of Poetry begins with a discussion of the opening lines of the 1967 version of Marianne Moore’s famous poem “Poetry”: “I too dislike it. / Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers in / it, after all, a place for the genuine” (1-3). Moore’s poem, and these lines particularly, would become a recurring note in my future explorations of poetry in the classroom.

Cover of Why Poetry.

A year later, I read another recently published “popular” book of poetry criticism, Matthew Zapruder’s Why Poetry. I liked Zapruder’s book better than Lerner’s—it met many of the same objections to poetry Lerner identified, but went further in its explorations and justifications for the art form in a more level-headed and accessible manner. In a departure from Lerner, Zapruder cogently defines poetry as a verbal machine for prompting the “drifting, associative, linking” (129) mental motion that he calls “the poetic movement of the mind” (133) in a way that seems to neatly sidestep many of the dilemmas and disjunctions I’ve found surrounding other attempts at denominating the genre. I remember thinking that it would be a good introductory textbook if I ever taught a class that focused exclusively on poetry again. Which also made me wonder: Would I ever teach a class about poetry again? Should I?

Poet Marianne Moore with a cockatoo, 1954. Image courtesy of Getty Images/Life.

I wrote the course description for my spring 2018 sections of ENGL 1102 in haste after finishing Zapruder’s book. I had wavered between several other safer, saner possibilities for the class, but in the end, I decided to face what I feared the most: poems, poets, and poetry. The entire course would be centered around poetry; my students and I couldn’t avoid poetry or work around it if poetry was the class’s raison d’etre. In a nod to Moore, I titled the course “I Too Dislike It: Poetry and its Discontents,” and I wrote in the description that it would try to answer these questions: “What is poetry, exactly? What is it for? What does it do that other types of writing or art don’t? Why do so many people actively dislike (even hate) it, and why do so many people also actively love it? What about it is so polarizing and unique?” Perhaps if I honestly foregrounded the difficulties and uniqueness of poetry, the class could arrive somewhere different and wouldn’t find itself circling down the same tautological drains.

My idea was to start the semester off with the two books that had inspired the course, Zapruder’s Why Poetry and Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry, and then, with the shared vocabulary and concepts of these books, proceed into navigations of actual poets and poems. I wanted students to read lots of contemporary poetry published within the last five years, but I also wanted them to look at older works for comparison and contrast. I settled on the idea of pairing the contemporary volumes of poetry with older volumes considered classics, time-honored, and canonical. We would read the paired volumes in tandem with each other and think about them in terms of ancestry and influence, whether intentional or unconscious. I hoped the paired volumes would rhyme and do battle with one another, throw off sparks in their intersections and antagonisms. I paired Ross Gay’s 2015 celebration of nature and joy, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, with Frank O’Hara’s 1964 celebration of urbanity and pleasure, Lunch Poems. I paired Claudia Rankine’s essential exploration of race in America, 2014’s genre-bending Citizen: An American Lyric, with the original 1855 edition of Walt Whitman’s genre-bending exploration of the notion of America itself, Leaves of Grass. And finally, I paired Solmaz Sharif’s 2016 investigation of the lingering effects of war upon language, Look, with Adrienne Rich’s 1978 feminist investigation into power, love, and language, The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977. In addition, students would select and read a seventh collection of poetry of their choice in small groups and give presentations on what they discovered. It was a full slate of reading, but one I felt confident about as I headed into the semester with an admixture of butterflies, doubt, disbelief, and excitement. (I should mention now that my wife and I were expecting our first child in the second week of the new semester.)

So what actually happened during the course? My memories of the first month are blurred and fragmented. We lost time to snow days as well as to the birth of my daughter, and as a result we had online discussions of Zapruder’s book that I participated in from the twilight zone of new parenthood. I returned to the non-virtual classroom and observed my students from a bleary distance like they were performers in a play I couldn’t remember having agreed to direct. Soon enough we were back on the same, material page—but this time with a rough-hewn, new approach to reading poems cobbled together from suggestions in Zapruder’s book (e.g., read the literal words of the poem on the page first, don’t hunt for secret codes, draw or enact visually the poem’s movement, allow room for private associations) and dollops of Lernerian skepticism. I came to value the discussions about poetry we had together as strange islands of refuge and regularity in an ocean of sleeplessness.

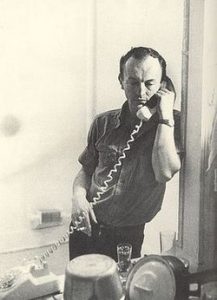

Photograph of Frank O’Hara via Wikipedia.

I thought O’Hara, Whitman, and Rich would all be accessible to my students. I was wrong. Some noticed and identified with O’Hara’s exuberance and joie de vivre, but for most of them the dense barrage of precise mid-1950s NYC bric-a-brac and proper names—the very bricolage and casualness of reference constitutive of O’Hara’s influential style—seemed to them not worth the effort to unpack. I was shocked to realize that O’Hara perhaps will require a new readers’ edition with high modernist-style footnotes to be decipherable for future generations (one that might threaten to take all the breeze and nonchalance out of O’Hara’s lunchtime shirts and sails). With Whitman, I allotted too little class time—only one week—which wasn’t enough to really dig into Leaves of Grass (even the “lean” 1855 edition that we read). A number of students also questioned the efficacy and morality of Whitman’s fundamental proposition in “Song of Myself” that “What I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you” (lines 2-3). They wondered if Whitman had the right to speak for everyone he spoke for in the poem (black slaves, women, Native Americans, the elderly, the physically disabled, the mentally ill, to name only some of the subjects in “Song”). Whitman, they said, was also too dense and long-winded, and one student memorably compared him to the “stoned guy at a party who’s figured out the secret of the universe and wants you to know that he knows it, but doesn’t necessarily want to let you in on it.” She questioned his whole shtick, finding him a little absurd and dubious. Of the three “classics” we read, I had the most success with Adrienne Rich, but only after we spent time in class doing serious, almost line-by-line close readings of the first four poems in The Dream of a Common Language. Rich’s political urgency and plainspokenness were mostly welcomed, although some of the connections she called for between the private and public realms remained difficult and confusing for students to make.

Solmaz Sharif, the author of Look.

Students liked the newer books much more. They read Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, Citizen: An American Lyric, and Look more assiduously, embraced them more eagerly, and discussed them more openly. The books’ wide variety of stylistic approaches seemed to offer students more avenues of entry rather than causing dizziness; if one were confused by the obliquity of one of the airier, free-floating lyric sections of Citizen, for example, one only had to keep reading to encounter a re-centering, clear-cut narrative vignette about racial microaggression or a prose essay about Serena Williams. But what students were drawn to most in the contemporary works wasn’t as immediately connected to form or style: it was the content of the books. Sharif’s collection Look borrows much of its lexicon from the U.S. Department of Defense’s online Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, and her dual Iranian-American heritage allows her to dramatize the immediate and residual effects of the war on terror both in the Middle East and the U.S. in ways that my students found moving and disturbing. Sharif’s attention is centered on the way the language used by the U.S. government and media to describe war euphemizes and detracts from literal meaning, deferring emotional and physical immediacy. We spent entire class periods talking about the implications of words many of us had used fairly thoughtlessly for our whole lives, like “casualties,” “collateral damage,” and “homeland security.”

Cover of Citizen: An American Lyric.

Rankine’s Citizen, arguably the most celebrated and influential book of American poetry of the last decade, prompted similarly complex and wide-ranging class discussions about race, identity, and perception. Rankine’s use of the second person to avoid explicit racial descriptors in her prose-poem vignettes of microaggression forced students continually to question their own assumptions about who was who, and which characters they identified with. Citizen’s use of multimodal elements such as images of contemporary sculpture and photography, as well as the “situation videos” available on Rankine’s website, opened up conversations about poetry’s relationship with digital technology and the expectations poetry harbors as an (ancient) technology of its own. (Later in the semester, a group of students did a memorable presentation on the “Instagram poets” who use social media to distribute their poems to huge audiences and identified Rankine’s more artistically ambitious and complex project as both a predecessor and counterexample to Instagrammers’ work.) And although not nearly as explicitly politically charged as the work of Sharif and Rankine, Gay’s blissed-out poems about urban gardening, loss, death, and the mystery and inescapability of the body made us wonder why genuine expressions of joy had come to seem so few and far between in American literature and life. Gay’s Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude drew guileless magic circles and improvised transitory moments of community and openness that at their best translated themselves briefly from the page of Gay’s book into the classrooms my classes shared together. My students’ enthusiasm for contemporary poetry seemed roughly in keeping with the findings of a recent National Endowment for the Arts survey: that poetry reading has doubled among 18-24-year-olds in the five-year period between 2012 and 2017.

In an effort to address their distaste for the older texts, I asked students on the last day of class which single book they would remove from the syllabus and what they would replace that book with. Although there were slight variations in responses from section to section, Whitman or O’Hara mostly went out the window and were replaced with recent works by poets like Tyhemiba Jess or Danez Smith, writers of color students had researched for their presentations. Contemporary poetry seemed to offer students an unanticipated entry point into the fractured, attenuated world they inhabited in ways that current U.S. poet laureate Tracy K. Smith says “break… from the shorthand vocabulary of tweets and sound bytes” and “offer… [students] a necessary recourse to depth, strangeness, vulnerability, and imaginative possibility.” Smith also argues that poetry invites students “to take their time, to move slowly, to process things gradually, which is an impulse counter to the breakneck pace at which much else occurs.” I was reminded that even though Marianne Moore begins her poem about poetry with an admission of her contempt for it, she immediately insists that “there is in / it after all, a place for the genuine”: what she later calls “imaginary gardens with real toads in them” (1919 original version of “Poetry,” lines 2-3, line 23).

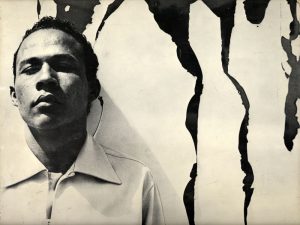

The last assignment of the semester was what I termed a “personal poetry narrative,” a short creative piece, the form to be determined by the student, about a student’s relationship with a particular poem, poet, collection, or poetry in general. I decided to do the project along with my students, and I wrote about Bob Kaufman, the legendary but much-neglected Beat poet famous for his practice of spontaneous oral proclamation of his poems in the streets of San Francisco, as well as the ten-year vow of Buddhist silence he took after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Kaufman broke that vow of silence in 1973 with the surprise recitation of a new poem, “All those ships that never sailed,” at an art gallery in Palo Alto, California. For me, it’s one of the most beautiful poems of the 20th century, and a prime example of Kaufman’s approach to poetry as something oral and pure, evanescent and magical, that could evoke change in the writer and the listener. I worked up a Google slideshow with images and some of the only existing audio and video footage of Kaufman, and I read my own personal poetry narrative to my classes on April 18, what would have been Kaufman’s eighty-third birthday.

Bob Kaufman, San Francisco, c. 1959. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Open Space, SFMOMA.

I didn’t realize it until late in the process of writing the narrative, but I was in part thanking my classes for the role they played in leading me back to a reconciliation with poetry. Here’s how I ended the essay on Kaufman, and how I’ll end this essay, too: “To be honest, one of the reasons I like poetry so much, and one of the reasons that so many other people dislike it and get impatient with it, is that it defies our conventional ways of using language and communicates at different frequencies than we’re used to hearing, sometimes at ones that we can’t explain or quantify. The types of frequencies and meanings one has to write poems about in order to express or access. I feel like I’ve been away from poetry for a few years, like I’ve even lost faith in it or betrayed it at times. Like the speaker in Marianne Moore’s poem ‘Poetry,’ ‘I too dislike it.’ And yet I know also, and have known for quite some time, that it’s at the heart of me and who I am. And that once I am ready to break my silence and return to it, it will be there waiting for me, huge and intransitory, its unscuttled ships ready to sail forever. Happy birthday, Bob Kaufman, and thank you for your heavy water that floats up in the air, like a miracle, like a blues, like a voice.” Thank you to all my students in ENGL 1102, Georgia Tech, spring semester 2018, for the heavy water of their voices and kind attention, too.

Works Cited

“April Is the Cruellest Month.” The Office Hour, April 6, 2017, episode. Podcast.

Charles, Ron. “Poetry reading by young people has doubled since 2012.” The Washington Post, September 12, 2018. Web.

Fallis, Jeff. “The Doubleplusgoodspeak of Newspeak: Poetry and Orwell’s 1984.” TECHStyle, April 20, 2017. Web.

Gay, Ross. Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015. Print.

Iyengar, Suyil. “Taking Note: Poetry Reading Is Up – Federal Survey Results.” Art Works Blog, National Endowment for the Arts, June 7, 2018. Web.

Lerner, Ben. The Hatred of Poetry. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. Print.

Lichtenstein, Jesse. “How Poetry Came to Matter Again.” The Atlantic, September 2018. Web.

Moore, Marianne. “Poetry” (1919 version). Poets.org. Web.

O’Hara, Frank. Lunch Poems. 1964. City Lights Books, 2014. Print.

Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf Press, 2014. Print.

Rich, Adrienne. The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977. 1978. Norton, 2013. Print.

Sharif, Solmaz. Look. Graywolf Press, 2016. Print.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass: The First (1855) Edition. Ed. Malcolm Cowley. Viking Penguin, 1986. Print.

Zapruder, Matthew. Why Poetry. HarperCollins, 2017. Print.