This post is the fourth in a series about our class project in “Teaching Composition.” Read Part One, Part Two, and Part Three.

In addition to learning about theories of rhetoric and writing, the future English teachers in this fall’s “Teaching Composition” course needed to think about how to apply those concepts when they enter the classroom. In the final post about the students’ infographic projects, I’ll share a classroom tool created by Caitlin Porter and Lindsey Andrews, which guides students through the writing process. I also hope to explain how the students theorized writing as a process while creating their infographics.

In previous posts, I claimed that this assignment provides practical, marketable skills for students in the course. And while such skills are valuable, they do not exist in a vacuum. At a liberal arts institution like the University of St. Francis, it is just as important for students to understand why we might wish to communicate in an infographic format as it is to be able to execute a successful infographic–maybe moreso. Theory and application worked hand in hand: we read and discussed the New London Group’s theory of multiliteracy–which argues that in an increasingly digital, connected, and diverse world, we are not literate until we can communicate in visual, spatial, oral, and other modes that complement writing–and we practiced creating multimodal texts by designing infographics for real, diverse audiences.

In a recent Hybrid Pedagogy article, Ashley Hinck, a professor of Digital Media and Communication Arts at Xavier University, points out the limitations of digital platforms like Canva, Wix, and Giphy that allow users to make digital media by dragging and dropping into templates. She warns that the drag-and-drop approach to digital making can actually limit our creativity by making decisions about the design of a product for us. This is troubling, Hinck argues, because it replicates more traditional models of education in which students follow prescribed steps to get the “right” answer, without really thinking for themselves. I’ve been thinking about this article quite often since I read it almost a year ago. On the one hand, I take Hinck’s point. On the other hand, if I want to incorporate digital making into English classes, I need to use templates. If we did not use tools like Canva and Piktochart for this project, we would all still be working on it, because we would all still be learning to code. And that wasn’t the point of “Teaching Composition.”

An important point of the course, however, was for students to develop their own critical approaches to digital writing and the role of digital media in shaping how students learn to write today. Along with numerous conversations about how, for example, the prevalence of texting is impacting students’ attention span and writing style, or the difference between freewriting in a notebook and on a laptop, we also worked through the affordances and limitations of digital platforms for writing and other forms of multimodal communication.

While workshopping the infographics in class, students pointed out the things they couldn’t do in a platform like Canva, and we brainstormed to find a work-around solution. And when Caitlin and Lindsey encountered too many limitations in the first tool they tried, they started over with another. In other words, the students arrived organically at the point made by Dr. Hinck which, in turn, gave us an opportunity to talk through the affordances of digital media platforms. While one solution to the problem of templates might be to reject them altogether, another is to think creatively about how to achieve the desired rhetorical effect within the limitations we are given. This dilemma starts to sound a lot like the writing process itself.

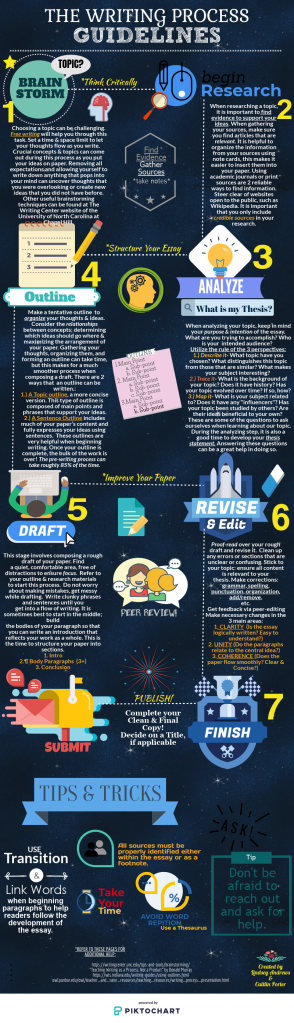

In his new book Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay (and Other Necessities), John Warner argues that writing is not really writing if it is not aimed at real readers. With real audiences in mind (audiences which, as we learned from Walter Ong in our class last semester, are always at least partly a “fiction” that writers imagine), students designed their infographics to be read and engaged with. For Caitlin and Lindsey (and Carolyn and Hannah, who also focused on the writing process), the form of the infographic intersected in complex ways with the philosophy they espoused. If writing is a non-linear process, then a linear text walking students through that process undermines its own claims. The students wrestled with a design problem that was also a rhetorical problem: how to make an infographic, which is usually encountered on a screen, visualize the modular, mobile, non-linear writing process? Caitlin and Lindsey used the spatial affordances of the form to show the steps of the writing process without implying that they are rigid or even sequential.

Donald Murray could not have known it when he wrote “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product,” but new media forms like the infographic reinforce his central argument even as they reinvent that argument. Multimodal writing expands the categories of prewriting, writing, revising, and editing to incorporate everything from trying–and rejecting–digital tools to resizing and reorganizing images to experimenting with color schemes. Here’s how Caitlin and Lindsey approached the project:

The focus of our infographic was the writing process from a student’s point of view. We are both secondary education majors and wanted to construct a visual aid that we could see ourselves using in our own classrooms. Knowing where to begin is one of the main difficulties that middle school and high school students face when composing papers, we were hoping to make the writing process seem less intimidating with the construction of this infographic.