The poster for the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear.

On November 18, the Georgia Tech Writing and Communication Program hosted the Fall Communication Colloquium in which two Brittain Fellows presented on work their students have been doing in class this semester. The presenters did such a wonderful job generating discussion during the sessions (a link to an archive of the Twitter backchannel is here) that we asked them to share their work on TECHStyle in order to continue the conversation. Jesse Stommel’s post, Feed: Texting, Twitter and the Student 2.0, discusses why and how he uses Twitter in the classroom. In this post, Diane Jakacki discusses her experience integrating a text that unfolded in real time as she and her students were studying it.

A Text and an Opportunity

Teaching a course on the rhetoric of celebrity culture, by its very nature, requires an adaptable, reflexive approach to lesson plans and assignments. While my course involves basic critical readings in mass media, gender and theories of selfhood and authenticity, supplemental texts pertaining to current events are necessary to demonstrate the speed and emphemerality of popular cultural subjects and events. In order to truly demonstrate the increasingly powerful hold popular celebrity culture has on our society, I believe a case study-approach allows the classes to examine questions of rhetorical appeal and the relative impact of real versus “pseudo-events”, to use Daniel Boorstin’s term.[1] In other words, we must delve into the peccadilloes of Snooki from The Jersey Shore, the latest philanthropic mega-gift by Bill Gates, and the increasingly celebrity-mimicking behavior of politicians as they run for and hold office. But what happens when current events that are unfolding over the course of the term are incorporated into the syllabus? Is it meaningful or distracting to focus a significant amount of class time and percentage of the course mark to analysis and interpretation of an event that does not appear to demonstrate its value as a case study until the event has actually occurred?

Watching The Daily Show in preparation for a lecture in mid-September, I listened as Jon Stewart announced his Rally to Restore Sanity event. While details were sketchy at best, I thought that there would be enough teachable moments in the promotion and execution of this event for students to articulate what they had been learning in class. The timing was also attractive: the election was looming and the lines between important issues and ridiculous posturing were blurring ever more. It was also midterm season.

The Assignment

The assignment I envisioned was for students to follow the promotion for the rally and Stephen Colbert’s counter-march, on The Daily Show and The Colbert Report and other television programs as well as in newspapers, and blogs. Students were to choose to focus their energies on either the rally or the march, in an effort to help them make sense out of the apparently competing events. They were to articulate a thesis about what they believed the rally might accomplish, and then engage in a close critical analysis of the event itself, examining the words, tone, body language, and imagery used by Stewart, Colbert, the rally attendees, as well as the media reporting on the event. I was interested in having the students express their observations in poster-form; however the event’s root in video and electronic media called for an expansion of multimodal elements to include embedded video and links to other websites. The posters were due a week after the event occurred, and I wanted students to be able to incorporate as much post-event analysis as possible. So the poster became an “electronic poster”, loosely identified as a composite of thesis, arguments, evidence and conclusion within a single frame. Students could use PowerPoint, Prezi, Glogster, AfterEffects, Photoshop, or any other application that allowed them to incorporate photographic and visual images, text and graphics in this way.

Since this represented a departure from our original midterm assignment (a textual essay), I asked the classes to vote on whether or not they wanted to undertake this project. Not surprisingly, the outspoken enthusiasm of some was almost equally matched by the confusion and concern of others. I acknowledged these concerns, and was as transparent as I could be: I, too, was a bit unnerved by the idea of teaching something that was so unstructured. Unlike a predefined event such as an election, or an Olympic games, or award season coverage, we could not identify or anticipate a narrative arc for this event. Stewart’s hints at disorganization in the planning process and confession that he had no idea how many people would attend the rally, as well as his hesitation to give details – on his show and in interviews – suggested that he, too, was worried about the outcome. I might be left doing a very fast-dance with my students to figure out how to salvage a mid-term project that never really happened – especially one worth ten percent of their course mark.

Research and Preparation

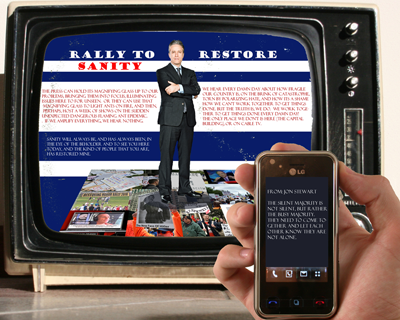

This student used Photoshop to create an intuitive, richly layered argument. Project courtesy John Shinsato.

In the six weeks between the rally announcement and October 30, the date on which it was to occur, I spent significant class time working with students to help them prepare. I distributed a list of questions about the event that were designed to help students articulate their theses and arguments, and assist them in identifying the evidence they would use.

I encouraged students to focus on the presence and performance of either Stewart or Colbert, since I had made the assumption, perhaps a dangerous one, that Stewart and Colbert would appear at the rally, at least in part, in the guise of their characters, and I wanted the students to be able to recognize the tenor of these characters. Each week they watched episodes of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report, after which I gave them quizzes that they worked on in teams – each quiz focusing on a different rhetorical aspect of the shows as well as Stewart and Colbert’s styles of communication via their onscreen characters. I wanted the students to closely examine how each man acted within the context of his show: how they interacted with guests and cast members as well as with one another, how they spoke to their audiences, who those audiences were, etc., in order to sensitize the students to Stewart and Colbert’s satirical approaches toward current events, issues, and politics. This was particularly important, as it became apparent that a number of the international students in class had never even heard of The Daily Show or The Colbert Report, let alone the topics covered in both shows. By analyzing verbal and nonverbal communication, the approach was weighted equally with content.

We spent several class sessions working in teams to give and get feedback on each student’s concept. They discussed the answers to their questions, reviewed the applications available to them, and helped one another in learning how to use these approaches. An overwhelming majority of the students chose to use Prezi for their posters. Prezi is a web-based presentation tool that, in the words of one of my students, acts like “PowerPoint on crack”, allowing the presenter to move from argument to argument through a series of animations (the following poster is courtesy of Will King).

The students mastered the application within a very short time and seemed to enjoy the experience. One of the most exciting aspects of this process was watching the students assist one another with elements of their projects –when someone needed assistance with some visual or graphical element of their presentation, one of their classmates invariably jumped in to guide them.

Learning Outcomes

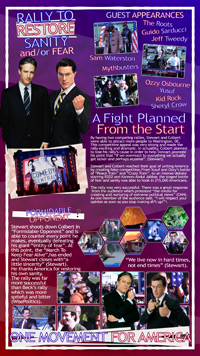

This student used his poster as the basis for a more complex visual analysis. Click on the image to watch his video. Project courtesy Gabe Auyeung.

My concerns about the event resulting in disaster were unfounded. Over 200,000 people attended the rally, some 500,000 viewed it online and another 2 million watched on television.[3] And while the show may not have been as funny or as polished as The Daily Show or The Colbert Report (a disappointment shared by a number of my students), the rally appears to have touched a chord with them. More to the point, it provided some very provocative elements for my students to develop into sound multimodal artifacts. Many of the students demonstrated particular insight regarding the interplay of those who attended the rally and the media pundits who observed it with discomfort and distaste. Many students responded to my encouragement that they incorporate an array of media and links to other sites into their posters, and in some cases the results were particularly striking.

Not only did they highlight the rally in a meaningful analytical fashion, but they also examined the grassroots rhetoric of the picket sign campaign that Stewart initiated.

What would have happened if the Rally to Restore Sanity had been a dud? If the event had been cancelled, or if no one had shown up, or if Stewart hadn’t been able to articulate the zeitgeist that inspired the stunt, I originally thought my students and I could not have accomplished much more than a discussion of these failures in class. I thought it would have been impossible to create an artifact out of something that did not happen. I was ready to state that my worry was a real one, and the potential for failure – failure in the sense of committing students to such an assignment – would have been significant enough to act as a cautionary tale against undertaking such a project. However, it occurred to me that I was looking at this process from the wrong vantage point. Students, especially those steeped in the sciences, are accustomed to and comfortable with experiments that succeed or fail, where both success and failure are acceptable outcomes, and the process is the point. In fact, by emphasizing the promotional and developmental aspects of the Rally to Restore Sanity in this project, I was encouraging students to do what comes naturally to them anyway, although perhaps not always in the guise of an English class. Coming from an historiographic background, used as I am to being able to identify the end result of something, I didn’t give the process enough credence. In hindsight, committing to such a leap in teaching is healthy, enriches the subject matter, and encourages creativity and analytical skills with the students. I don’t know how often such opportunities will come my way, but I look forward to incorporating them into future syllabi.

I would be interested to learn if and how other instructors have incorporated such unplanned and unstructured events into their syllabi. Please share your thoughts in the comments section below.

[1] Boorstin, Daniel. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. New York: Atheneum, 1982.

[2] Poster image from Rally to Restore Sanity website. (http://www.rallytorestoresanity.com/) Accessed 20 November, 2010.

[3]Statistics are from Wikipedia entry on rally, but have been cited in various sources across media. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rally_to_Restore_Sanity_and/or_Fear”) Accessed 20 November, 2010.

Pingback: Tweets that mention TECHStyle | Blog | Teaching in Real Time -- Topsy.com

Pingback: TECHStyle | Blog | Feed: Texting, Twitter, and the Student 2.0

Pingback: TECHStyle | Blog | More Adventures in (Hyper) Real-time Teaching