At Stony Brook University, where I spent my Fall Break, I learned all about the Curse of Knowledge … from Alan Alda. A few feet away from me, Alda gave the keynote speech at the Center for Communicating Science’s Fall Institute, explaining passionately that once we know something really well, we forget what it’s like not to know it. And once that happens, we have a lot of trouble communicating our knowledge effectively to others.

Scientists, the CCS says, are constantly afflicted by this curse. They can communicate well with other scientists within their specializations. But they don’t communicate well with everyone else—with the man on the street, with public officials and policymakers, with the media, with officials at their institutions, etc. Caught up in the details of their work and the jargon of their fields, they overlook the human side of the equation—the need to explain why their work is important, how it connects to other fields, and how it affects normal people outside of the university in the real world.

As a teacher of English and the Assistant Director of the Communication Center, I agree with almost everything that the Center for Communicating Science says—except for their focus on scientists. Most professionals are similarly cursed—engineers, mathematicians, even English teachers. Just look at the title of my dissertation: “‘Daemonic’ Forces: Trauma and Intertextuality in Fantasy Literature.” I know what I mean. My co-workers may know what I mean. But who else does? (My father certainly doesn’t…)

The Center for Communicating Science focuses on science because of its importance in today’s society, because scientists have a responsibility to the world, and because science has such a potential to make the world better—if people recognize that fact. Alan Alda tells a story that he heard from a US Congressman: in an important meeting that was to determine policy and funding, a handful of scientists sit across a table from a handful of Congressmen. As the scientists talk, the Congressmen begin passing notes back and forth to each other. Do you know what these guys are talking about? … No … Me neither … Well, I’m not voting to give them funding …

And students across Georgia Tech, learning to communicate within their disciplines, are developing similar problems. The CCS says, “Young scientists typically are schooled to focus on being precise and accurate in what they say and write—their attention is all on what they are putting out, not on what their audience is picking up. But what good does it do to present important information in accurate detail, if no one listens, cares or understands?”[1] The Writing and Communication Program does an excellent job of stressing to students the importance of communication and of clarifying that communication is more than just the written word—it’s Written, Oral, Visual, Electronic, and Nonverbal. However, we teach that in First-Year Composition. After that, students retreat excitedly into their specializations. Some return to us, taking other communication-related course. But most are happy to have finished their required English courses and don’t look back: Thank goodness, they think. Now that I’m done with English class, I don’t have to worry about writing or communicating anymore!

The horror.

Ultimately, people often recognize that communication involves putting forth ideas into the world but forget that, for communication to be successful, those ideas have to be received and understood by others. Alan Alda and the Center for Communicating Science clarified a few of the problems that highly educated people have with communication. 1) Specialized language. 2) The inability to recognize that clarifying ideas ≠ “dumbing it down.” 3) A tendency to lecture—that is to put a protective barrier between yourself and your audience so that you’re talking at the audience instead of to real people. The solutions they offered? Teach scientists 1) to connect more with other people and 2) to distill their message.

Communication, explained Alda, or the process of personal exchange and listening, mirrors the three stages of love: lust, infatuation, and commitment. In the first stage, there’s an attraction based on body language, tone of voice, and the personality that comes across in the physical. Two bodies communicate with each other nonverbally to make a connection. In stage two, infatuation, emotions become important to the exchange—an emotional response needs to be created to keep things going. Only in the third stage, commitment, do you actually have to start listening.

Alda suggests that scientists need to learn communication in all of these areas: to recognize the importance of (and how to use) nonverbal communication, to emphasize an emotional connection to their work, to listen, and to talk with the intent of being listened to—not just heard but really listened to. But how to do this? Alda and CCS suggest using improvisation to help scientists make connections to others. Not all out Who’s Line is it Anyway? improv. CCS’s goal is “to help scientists and health professionals be more spontaneous, direct, personal and responsive when they communicate. … But it does not aim to turn scientists into actors. It does not teach them to act, or to pretend, or to get a laugh, or to ‘dumb down’ science.”

I’m no actor, so I was nervous about the improv portion of the Fall Institute, but I got over it quickly. We played simple games. Paired up with one gentleman, I had to pretend I was his mirror image … and then slowly take control. In another game, I had to take a blank sheet of paper and pretend that I was showing the others a favorite photograph. In another, half of us stood in front of the rest, and we just stared at each other. What I found after three hours of play was that I felt extremely comfortable with these people. Conversation flowed more easily, and I cared more about what they had to say.

[Improv] aims to teach [scientists] to connect—with their audience, with their colleagues, with their students, with their friends, with any of their partners in communication. … Improvisation is a playful, surprising way to help scientists learn by experience that communicating is a shared enterprise, not a one-person show. The goal is to pay close attention to other people, to notice other people’s reactions and to respond freely, showing their own personality and passions, without fear or self-consciousness.

We’ve all been to conferences or classes where the speaker is not really “present”—s/he’s reading a paper or otherwise putting a wall between him/herself and the audience, definitely not connecting to real people. But when talking/listening to another person, our social attributes can kick in and our emotions come across. We make clear connections. We use imagery and metaphor, enthusiastic hand gestures, and passionate tones. As the host of Scientific American Frontiers, Alda “noticied that, to the extent that I could get scientists to be spontaneous—not to lecture but to give and take with me—they became more watchable. They were more alive, and easier to understand.”

These connections help us to communicate. Learning to distill our message does so as well. Think of the old elevator pitch—how do I explain what I do in 30 seconds to two minutes? How do I explain it to someone unfamiliar with my work, with my field, or with my jargon? CCS gives a number of pointers:

- Avoid jargon. Use conversational language. If you must use a technical term, explain it (explicitly or by context) before you use it.

- Know what your main point is. Focus on making that clear and memorable.

- Answer the “so what” question. Why is this important? What impact could it have? Why should the listener care about it? Why do you care about it?

- Tell a story—what’s surprising, exciting, difficult, upsetting, or mysterious about your subject. Include the features a story usually has: a time element, characters, plot, suspense.

- Don’t be afraid to show emotion or to get personal. Emotion is memorable.

- Once your listener is interested, you can add layers of complexity and detail. You are aiming to make the listener want to know more.

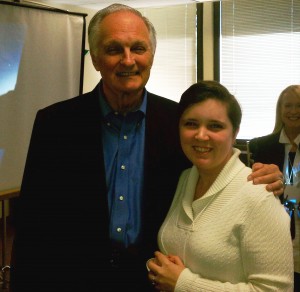

Alan Alda with Brandy Ball Blake, Assistant Director of the Communication Center, at the Center for Communicating Science Fall Institute–Stony Brook University.

They go into more detail than this, but that list should give you a sense of the basics. And how true! Why don’t more professors and advisors suggest these basic principles? Distilling your message is about being clear and vivid, not dumbing it down. And learning how to do this will only help.

My dream–to have a setup like CCS and to develop workshops like they have: Distilling Your Message, Improvisation for Scientists, Writing to Be Understood, Using Digital Media and Connecting with the Community–this dream is embodied by Georgia Tech’s Communication Center. In order to add to our growing number of workshops and to further reach out to the Georgia Tech community, we plan to use the materials that CCS provided us in order to develop and implement similar workshops because we share their goals. But more important than developing these workshops is cultivating an environment in which students and faculty across disciplines understand how important clear communication is and are willing to work on it–an environment that examines its own communication with excitement rather than disinterest, as a primary concern not a secondary issue. And we all have to work together to achieve that goal.

[1] All quotations taken from Center for Communicating Science handouts by Elizabeth Bass, CCS Director.