Students viewing “Meadow” by Alex Katz at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, February 2018.

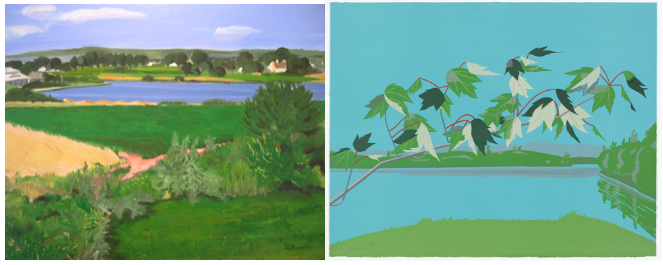

Making podcasts about visual art presents a challenging multimodal question: How can a podcast, an entirely oral medium, account for all of the complexity, subtly, and abstraction in a painting or sculpture, an entirely visual medium? Producing a podcast about a single piece of visual art—this was my students’ task—would require not only focused research into the artist and any critical reception of their work but also the development of a specific and functional aesthetic vocabulary. The process of growing and revising aesthetic vocabularies—methods for descriptive analyses of the choices, processes, and effects in art—was at the heart of this course. In class, students and I would develop lists of words and phrases that could be used to describe pieces of visual art, often thinking across mediums by comparing them to the New York School poems we were reading. For example, I’d offer them two seemingly similar works, like “Bright Day” (1973), a painting by Jane Freilicher, and “and students would construct descriptions that responded to the fundamental question, “What do you see?” This seemingly simplistic question allowed students to look at the paintings without overburdening their looking with expectations about symbolism, narrative, and mimetic representation. While the pastoral landscape in Freilicher’s painting seemed stable and innocuous at first, students would come to see the ephemeral, abstract planes and collaged pockets of color that resist coherence into a world of stable perspectives. The painting suddenly became about directionality, the textures of soft, natural surfaces, and, as the title suggests, light itself. Following the subtle revelations in our discussion of Freilicher, the Katz lithograph was brand new, too. As I’ve written before about this process:

Suddenly, what students admitted had at first looked like traditional landscape paintings became ways of approaching talking about the intricate challenges of avant-garde poems: the blurring of depths and mysterious invitation to narrative in the Freilicher painting began to resonate with [James] Schuyler’s “Freely Espousing”; the almost-cartoonish flatness and overwhelming surface of the Katz lithograph reflected the off-kilter buoyancy of [Kenneth] Koch’s “To You.” The more they looked and read, the more students began to exchange received language like “random,” “confusing,” and “chaotic” for generative descriptors like “textured,” “overexposed,” and “composite.”

“Bright Day” (1973) by Jane Freilicher [left] and “Late July 1” (1971) by Alex Katz [right]

Students viewing “Manteneia I” by Frank Stella, September 2019.

These in-class discussions were supported by a class visit to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (which offers a free “Second Sunday” every month), picking a day early in the semester where all 75 of my first-year writing students would spend an afternoon looking at paintings by Robert Rauschenberg, Josef Albers, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and others. The public-private experience of looking at art in a gallery, of being overwhelmed, uncertain, and excited about these unfamiliar visual surfaces is certainly part of the pleasure of asking “What do you see?” To concretize these feelings, students were tasked with completing a generative questionnaire by recording their visual, sensory, and intellectual experiences about specific artists. One student wrote about Frank Stella’s “Manteneia I” (1968), “It feels like a mix of both abstract expressionism and a logo with its use of solid colors and geometric shapes.” Another wrote, “My mind longed for resolution and to see the end of each arc of color.” Yet another was both overwhelmed and comforted: “I love ‘Manteneia I.’ The symmetry and color scheme immediately put my mind at ease.” About Philip Guston’s “Untitled” (1973) students wrote:

“‘Untitled’ immediately strikes me as sushi”

“‘Untitled’ immediately strikes me as sushi”

“as if its made of bubble gum”

“some sort of meat cubes”

“not my favorite to be frank”

“predates Cartoon Network”

“a departure”

“disturbing”

“it was great”

One can imagine aggregating these descriptions into a pretty entertaining podcast about a painting. But how would students make such a podcast?

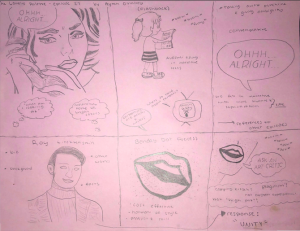

Student storyboard for Episode 27 of “The Lonely Palette” on Roy Lichtenstein.

I adopted the incredible podcast The Lonely Palette, created and hosted by Tamar Avishai, an adjunct lecturer at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for my students to learn how to conceptualize and plan their own podcasts. Describing itself as “the podcast that returns art history to the masses, one painting at a time,” The Lonely Palette offers listeners an in-depth and accessible portrait of the aesthetic, historical, biographical, and cultural significances operating in a single piece of visual art. Like with their visit to the High Museum, students responded to a questionnaire about multiple episodes of The Lonely Palette that allowed them to familiarize themselves with the podcast’s form, tonal range, and techniques, and investigated Avishai’s construction of the significance of the question “What do you see?” One of most effective techniques in The Lonely Palette is each episode’s cold opening where, before any introduction or context, listeners are met by the voices of museum-goers responding to exactly that question, “What do you see?” as they stand in the gallery looking at a painting. As listeners we’re not there in the gallery with them and privy to the visual information that inform our own descriptions, but these carefully arranged reactions document multiple viewers’ responses, often ranging from the ecstatic to the suspicious, the specific to the obvious, and create a generous shared space for us as listeners to also try and test our own responses to the painting. Students also create a storyboard for one of the four episodes they listen to, like the one featured here on the episode about Roy Lichtenstein’s “Ohhh…Alright…” (1964). These storyboards, which are both textual and visual, help students bridge the challenging process of organizing descriptions of visual art in an oral medium.

My students followed this process in my Spring 2018, Spring 2019, and Fall 2019 courses and each semester they’ve produced impressive podcast episodes, some exploring well-known avant-garde artists like Sol LeWitt and others researching “minor” New York School artists such as George Schneeman and Joe Brainard. Making their podcasts, students used their experiences visiting the High Museum of Art to consider the relationships between viewer, curator, artist, and the art object itself. This rhetorical awareness of the aesthetics of making and looking, and how art affects public and personal space simultaneously, allowed students to produce insightful podcasts in which, as first-year engineers and computer scientists, they become informed amateur art historians. The eight examples below highlight the range of communicative challenges offered by such an assignment. The techniques that students experimented with to explore visual art in the popular medium of a podcast include the production of detailed written descriptions of visual art akin to process descriptions in technical writing, creating an informative and engaging listening environment for an audience, utilizing primary and secondary sources in multiple mediums, and translating the discourse of an expert to a general audience. More examples as well as assignment sheets for these podcasts can be found at my professional website here and here.

On Peabody #29 by Al Taylor, from “Al Taylor, What Are You Looking At?” exhibit at the High Museum of Art (Spring 2018):

This group returned to the High Museum to record strangers’ responses to Taylor’s work in the gallery, which is a difficult and ambitious activity. The results are great, showing the range of skeptical, imaginative, and wonderfully bizarre descriptions that might emerge from a conversation at the museum. Throughout the podcast there’s a passion and interest in the exchanges between hosts that is exciting to listen to.

On Pipe Dream 2 (1986) by George Schneeman (Spring 2018):

This group’s podcast is well-organized, easy to listen to, and is full of subtle conversational techniques that recreate a natural progression of conversation and thought. The progression of the conversation into representations of gender is exactly right, but this group also makes an important, subtle turn to suggest that while this reading of Schneeman’s collage is vital you can also see the collage more literally as this self-reflexive artifact. For a New York School artist like Schneeman who hasn’t been widely studied or shown, this podcast is a significant contribution to the study of his work.

On “A Jar of Forsythia” (1990) by Jane Freilicher (Spring 2019):

This podcast on Jane Freilicher’s “A Jar of Forsythia” is wonderful. The podcast’s editing and production, use of music and transition, descriptions, interpretations, aesthetic vocabulary, use of sources, organization of information, and its unexpected insights are all impressive. The comprehensive description of the painting early in the episode is extraordinarily specific and insightful–especially in the bold, graceful use of color descriptions to bring the painting alive for listeners. The other host’s surprising insight into how this seemingly random arrangement of materials happens to be a global collage of everyday life is wonderful and charming. As a listener, I was willing to follow these hosts through any number of interesting interpretations and observations, which means they’ve earned my trust as a listener. The editing and production value are fantastic, especially in the choice of music that so effectively emphasizes and illustrates the mood and tone of the painting.

On “Grand Street Brides” (1954) by Grace Hartigan (Spring 2019):

In this podcast on Grace Hartigan’s “Grand Street Brides,” I love the outside viewer saying that the painting makes her “uncomfy.” One host’s description of how the painting poses two related feminist questions or crises is perceptive and another host’s addition of the Picasso reference is important acknowledgement of lineage. The way the podcast turns to the painting as a critique of capitalism and grounds this in Hartigan’s biography based on where she lived and her proximity to the bridal shops in the Lower East Side is excellent.

On “Wall Drawing 901” (1999) by Sol LeWitt (Spring 2019):

I’m so impressed with the level of production and depth of descriptive analysis in this podcast on Sol LeWitt. These are some conceptual and organizational complications, especially early in the podcast, but the podcast’s ability to address the experience and implications of LeWitt’s work is excellent.

On “Nancy Diptych, no. 283” (1974) by Joe Brainard (Spring 2019):

The descriptions at the beginning capture the spontaneity, surprise, and strangeness of first looking at Joe Brainard’s work. It’s funny how prominently the fried egg is mentioned in those descriptions but that no one directly says that the image of Nancy is a cartoon. The questions this group poses about the diptych–is this a comment on girlhood? how is this related to his other Nancy works? what does it mean that there are these two panels with different stylistic choices? is this one work or two?–are all excellent routes of investigation paired with substantive, insightful answers for listeners.

On “Yellow Body” (1968) by Robert Rauschenberg (Fall 2019):

This podcast does an excellent job of unpacking the aesthetic and cultural implications of Rauschenberg’s silk-screened collage, even making the connection between the title and large yellow swath of color and an ongoing public health crisis in the 1960s related to hepatitis, which yellows the skin. The students editing, organizational, and music choices make for an engaging, listenable podcast that opens up Rauschenberg’s work to new insights.

On “Sky Cathedral” (1958) by Louise Nevelson (Fall 2019):

There’s a meditative, calm tone to this podcast that matches the aesthetic, devotional quality of Nevelson’s “Sky Cathedral.” The students’ descriptions of the piece’s vertical motion, spookiness, and that it is a sculpture “constructed rather than carved” show their unique attention to this complex, uncommon work. As they say, “Sky Cathedral” embodies “a dissonance that invites you to sit by the sculpture and look at it.” Incredible. It is “as if her art seeks to show places in between the worlds we know.” These are exactly the kind of insights that make this assignment so productive for students and so much fun to teach.