For my second soundbite-focused post, I’m already deviating from the original plan by covering not so much a soundbite as the name of an entire movement. I’ve been wondering lately about the awkward resonance of “Occupy Wall Street,” the way that first word “Occupy” provokes so many distinctive interpretations: it can suggest invasion, colonization, aggressive seizure of territory; less aggressively, it can simply mean occupying a position, both in the sense of physical space and a mental perspective; and of course it echoes occupation as work, employment, along with the work we do at work (on our best days), when we are intensely engaged in (occupied with) a task.

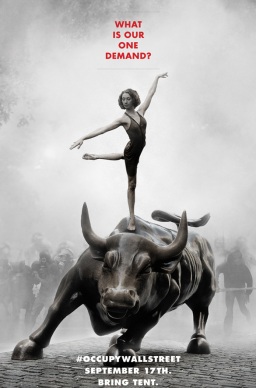

So what does it really mean to “Occupy Wall Street?” For a variety of reasons (all of them lame), I have yet to attend an OWS event in Atlanta, and certainly not in New York. I have occupied neither park nor street nor quad nor sidewalk, which makes me wonder if I can really say that I’m part of the movement, and not just an observer of its viral video. And yet, I think the name “Occupy Wall Street” activates some redefinition of the criteria for participation. I mean that the decision to name the first protest gathering “Occupy Wall Street” (see the Adbusters poster to the right) seems deliberately provocative; it winks at you, and unless you’re one of the louts Matt Taibbi quotes in this recent article, too unimaginative to understand protest as anything but envy, you apprehend immediately that the last thing OWS protestors want is to literally occupy Wall Street—as in work there.

So for those of us watching at home, “Occupy Wall Street” does something interesting rhetorically. It permits us to redefine occupation. And it permits us, winking all the while, to see that OWS is in a lot of ways just a (deliberately?) poor name for the movement that’s sprouted from that first September event. To half-quote Inigo Montoya, it does not mean what you think it means.

There’s a rhetorical figure that’s actually called occupatio, though it’s more commonly—and appropriately—named preterition. It occurs when a speaker or writer “describes what he will not say, and so says it, or at least a bit of it, after all” (see Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric).The OED defines it as “a figure by which summary mention is made of a thing, in professing to omit it.” “Occupy Wall Street” is almost the reverse of this: summary omission is made of a thing, in professing to mention it. Forgive me for that. The real reason I bring up occupatio is it’s another example of a poorly chosen name. Why would a word etymologically linked to taking, seizing, possessing, etc. be attached to a rhetorical figure that’s all about avoidance, evasion, side-stepping? The Rhetorica ad Herennium, influential book on rhetoric popular in the Middle Ages, seems to be the source of the confusion; H. A. Kelly suggests in this article that the anonymous author mistakenly substituted occupatio for occultatio, and the misnomer just stuck around after that, particular in Chaucerian scholarship. But Kelly also submits that there was

some justification in the text itself for thinking the term appropriate. The final example given for the figure runs as follows: “I do not mention that you have taken monies from our allies; I do not concern myself … with your having despoiled the cities, kingdoms, and homes of them all. I pass by your thieveries and robberies, all of them.” In other words, I am otherwise occupied, preoccupied.

In other, other words, “I can’t possibly be bothered with this, bothered as I am with other things, except I’m clearly bothered by this.” Maybe this is why you can still find occupatio on lists of rhetorical figures; even though a lot of people seem to agree it doesn’t make sense, you can kind of make it make sense if you try hard enough. Given Kelly’s example, occupatio/occupation is appropriate terminology … sort of. It just needs to be stretched a bit to accommodate preoccupation, or perhaps (pre)occupation.

I wonder if there is some potential insight to be gathered or connection to be made between the persistence of the inappropriate term occupatio, and the persistence of the ambiguous term “Occupy” in the Occupy Wall Street movement. Neither terms are really about occupation in the traditional sense of the word. To put it another way, the contexts in which both terms are used each suggest occupation and non-occupation, simultaneously. Yet “Occupy” is the word groups outside of New York choose to preserve, often dropping the “Wall Street” altogether: Occupy Atlanta, Occupy Oakland, Occupy Black Friday, etc. The word becomes a placeholder for a still ambiguous action. What the name has begun to underscore for me is the staying power of obscurity, and what I believe OWS has been dramatizing consistently since it began is a fascinating movement back and forth between indistinction and a vivid and often painful actuality: see the nameless mass of chattering UC Davis students, some seated with their arms linked, others milling about on the quad as if they just happened by the scene. See the now Internet-famous Lt. Pike brandish his jumbo pepper-spray canister, like he’s about to perform a magic trick, before dousing the students’ faces. The protest is immediate; you can almost see the moment when everyone there becomes a participant. It takes a few beats to get in sync, but eventually the group finds its voice: “You can leave,” is the chant that’s settled on, and though it’s not what I would have picked (much like I wouldn’t have picked “Occupy Wall Street”), it works, the police leave, and it’s breathtaking. Suddenly these students occupy so much of my thoughts, and almost all of my Facebook wall. I recycle posts, I try to extend the digital narrative, and I feel closer to being part of the movement, like being occupied is a way to be an occupier.

At the same time, I know my facebook wall in the next few days may fill up with other, unrelated items: Arkansas friends reacting to Razorback victories, fellow teachers venting about grading, Spotify, etc. OWS will grow indistinct again. Until the next video.

Before I stop, let me just say two things. First, I don’t write this to justify my complacency; while I believe OWS embraces different forms of activism, I suspect that still the best way to act is to get out of the house and into the streets/park/quad/bridge/bank/whatever. Second, I want to note that this whole naming/misnaming pursuit began after I read this lovely post about Occupy Oakland, which included these pictures of Snow Park before and after the police shut down the camp:

The “evacuated” park is packed with bodies, the “occupied” park is idyllically empty save a well-tended camp of some ten to 15 tents, and this all makes a kind of sense in our embattled country where corporations are people, special people who have the same rights as we do but none of the responsibilities. (Immortal people who won’t be troublesome and go to public parks; clean uncomplicated people without hands to cuff or eyes to teargas or bodies to arrest and jail.) They’re people, moreover, whose right to bribe politicians is protected as “free speech.” Without getting dramatically Orwellian, it’s reasonable to say that our words have lost some of the concreteness that made them useful.

She’s right, of course. And there’s no denying the weirdness of the images; why should so many more people respond to an order to evacuate than responded to an invitation to fill? My tentative answer is that this loss of concreteness the writer mentions is something in which the occupiers of Occupy Wall Street are finding their own kind of profit. They can shift back and forth between versions of occupation. These shifts may be no more predictable than the UC Davis chant, but perhaps this unscriptedness, this refusal to satisfy expectations—even the expectation to show up!—is precisely what Occupy Wall Street needs to keep its momentum.

Pingback: Are You Nobody, Too? Getting Dialogic in English 1101 - TECHStyle