In the first weeks of my 1101 course, The Allure of the Unreliable Utterance, I introduced my students to Socratic irony and to Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism. We watched snippets of The Colbert Report and The Daily Show—programs which rely on irony for their satirical humor—and we read Plato’s Symposium—a textbook example of dialogism (and which I like to think of as Plato’s love/hate letter to Socrates, who appears in the dialogue at his absolute best and his miserable, fraudulent worst).

Dialogism and Socratic irony are related, we discussed in class, in that they both leave the impression of uncertainty or contradiction. When Socrates introduces irony into an argument, he also introduces dialogism, because in the conversations that happen with Socrates, stable conclusions are exposed as insufficient or contradictory or not sensible—in short, messier, rougher than they appear.

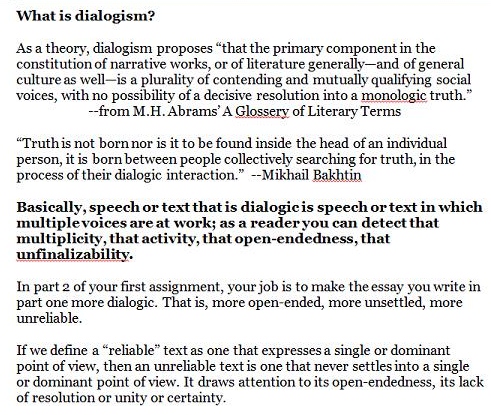

All of this content led to our first assignment, Getting Dialogic. I asked students to half-imitate the speakers in Plato’s Symposium—who take turns giving speeches about Love—by writing a short essay in which they defined a topic of their choice. Then I asked them to “get dialogic” on these first essays. As the screenshot above suggests, their goal was to revise their “reliable” texts (their traditional, familiar, thesis-driven essays) into “unreliable,” dialogic texts. The underlying assumption here is that, while according to Bakhtin all language is inherently dialogic, some texts are more monologic than others, and can be exposed as such; the thesis-driven essay is one example, relying as it does on linearity, logic and resolution. When we unleash our inner Socrates on these kinds of texts, we can both expose their limitations and complicate the subject matter.

I’m in the process of evaluating students’ dialogic revisions now. Here are a couple of examples from students who transformed parts of their essays into kinetic typography; here are a couple more from students who posted their thesis statements as facebook status updates; some students produced word clouds or infographics; others storified their essays, cut them up, or made them into video. I can’t say how impressed I am by their creativity and commitment.**

Still, there are major problems with this assignment, which I would like to address now, in the hopes of getting feedback, or simply articulating what has been troubling me about the project since I assigned it. There are the obvious questions: is it really sound pedagogical strategy to ask first-year writers to aim for ambiguity? Does it make sense to ask students to speak in multiple voices if they have trouble speaking or writing coherently in one? These are questions worth considering, but my primary concern has to do less with whether the assignment is appropriate than with whether it is feasible.

This must sound strange, given the list of student projects above; clearly the project is feasible—just look at the student work! To explain what I mean, I actually need to return to the Symposium.

For those unfamiliar with the dialogue, in the Symposium a group of distinguished friends get together to celebrate the talents of Agathon, writer of tragedies; rather than get drunk like they all did the night before, they decide to take turns giving speeches about Love. Fifth to speak is Agathon himself, whose speech is good the way Christopher Nolan’s movies are good: at once flashy and lazy; all style, little substance. When he finishes, Socrates does what Socrates does—compliments Agathon’s superior understanding before systematically destroying his argument. Here’s a key moment in the process:

I’d better jog your memory. I fancy it was something like this — that the actions of the gods were governed by the love of beauty — for of course there was no such thing as the love of ugliness. Wasn’t that pretty much what you said? It was, said Agathon. No doubt you were right, too, said Socrates. And if that’s so, doesn’t it follow that Love is the love of beauty, and not of ugliness? It does. And haven’t we agreed that Love is the love of something which he hasn’t got, and consequently lacks? Yes. Then Love has no beauty, but is lacking in it? Yes, that must follow. Well then, would you suggest that something which lacked beauty and had no part in it was beautiful itself? Certainly not. And, that being so, can you still maintain that Love is beautiful? To which Agathon could only reply, I begin to be afraid, my dear Socrates, that I didn’t know what I was talking about.It’s a common moment in Platonic dialogues: the sophist in Socrates’ sights is led into contradiction; he must abandon an argument that, only moments ago, he believed—or at least claimed to believe—was true. This moment resonates even more in the Symposium, because Agathon is a friend, not some representative of an oppositional philosophy Socrates has a vested interest in demolishing. Agathon is attached to his speech; it is with pain and fear that he sees it dismantled.

In my own assignment, I wanted to make it clear to students just how different their first essays and their revisions would be. In moving from “reliable” to “unreliable,” much might have to be abandoned—linearity, logic, conviction, closure—even as much was gained— dynamism, distinctiveness, interactivity. But what I really wanted was for them to feel a little of what Agathon feels; I wanted them to experience that moment when, looking over something you have previously written, you are forced to admit something like what Agathon admits: “I begin to be afraid … that I didn’t know what I was talking about.” This admission propels Agathon into new territory, makes him question his beliefs and also his talents. In this age of doubling down on myths and misconceptions, these moments of admission seem important.

In comparing their essays to their revisions, I have little doubt that most students will appreciate the contrast between “reliable” and “unreliable,” between “monologic” and “dialogic.” I am less convinced that many or any of them felt enough attachment to their original essays that the process of dismantling it pained them the way Agathon is pained. I worry that students will look at both products of the assignment and see them as independent artifacts that happen to address the same topic. But without that moment of Agathonian admission and realization, can students really come to an effective understanding of what Socratic irony can do?

Already I see things I can do to increase the potential for attachment. I allowed students to choose their own topics for their papers, in the hopes that they would choose something that they really care about. So many students are uncomfortable with open-ended assignments, I don’t think I’ll do this again. Next time I’ll follow the Symposium more exactly: each class will have its own symposium (minus the alcohol); instead of writing essays, students will give speeches on a single topic voted for by the class. Students may feel a greater attachment to their original work if they have to perform that work for a larger audience, if they and their work are part of an event and not “just” an assignment. (This revision seems so obvious that I’m embarrassed—pained—that I didn’t think of it before.)

Still, my concerns loom, and I have been wondering since assigning this project if “attachment”—the way I’m conceiving it—is even possible with most student writers. Agathon feels attached to his speech because Agathon self-identifies as a writer—the party is held in his honor! He just won a major award! Aristophanes is eyeing him enviously across the fig plate! But in seven years of teaching, I’ve met only a handful students who self-identify as writers. Far more plentiful are those who claim to hate writing and/or to be no good at it. And if students don’t identify as writers—if the possibility is barely on their radar—then they’re not going to feel anything close to what Agathon feels when Socrates goes after him … ahem… his speech.

Let me be clear: I don’t think this detachment issue is the result of some failure on the part of first-year writers. Could students cultivate a more generous and less dismissive attitude toward composition classes? Yes. (So could teachers, by the way; so could practically everyone.) However, I suspect the detachment issue has its roots not (only) in student attitudes to writing, but in the larger “problem” of postmodernism. I’ll let Umberto Eco explain:

“The postmodern reply to the modern consists of recognizing that the past, since it cannot really be destroyed, because its destruction leads to silence, must be revisited: but with irony, not innocently. I think of the postmodern attitude as that of a man who loves a very cultivated woman and knows that he cannot say to her ‘I love you madly,’ because he knows that she knows (and that she knows he knows) that these words have already been written by Barbara Cartland. Still there is a solution. He can say ‘As Barbara Cartland would put it, I love you madly.’ At this point, having avoided false innocence, having said clearly it is no longer possible to talk innocently, he will nevertheless say what he wanted to say to the woman: that he loves her in an age of lost innocence.”

Eco touches on dialogism here. All our words belong to other people; words have a life to them we can’t fully indulge on our own, and we know it, and so does everyone else! Granted, there are humanistic overtones to this idea, transcendental overtones, Whitman-y overtones (“For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you”), but Eco is right to characterize the postmodern attitude as a loss of innocence. If irony is inescapable, if we can’t speak innocently anymore, then how does that affect the ways in which we can self-identify as writers, or the extent to which we feel attachment to (and responsibility for) the words that we use. Within the postmodern condition, how much easier is it to claim, after contorting and twisting our words at will, that they came to us already twisted? Within the postmodern condition, how much harder is it to feel attached to a three-page essay on Love you write for a comp class, when you know how many times three-page essays on Love have been composed? Within the postmodern condition — which we may as well call the dialogic condition — how impossible is it to “get dialogic” when one already, all the time, is?

Eco introduces irony as the “solution” to the problem of postmodernism, and I’m inclined to agree with him. Let’s all say clearly that we cannot say things clearly! Ironists today go a lot further than Eco’s Barbara Cartland-quoting lover. I’m reminded of the recently popular “said no one ever” meme.

The irony is obvious, even excessive: No one said this … ever. I cannot stress enough how much this was never said! (And now, oddly enough, I’m reminded of book 5 of The Faerie Queene: “Me seems the World is run quite out of square, / From the first Point of his appointed Sourse, / And being once amiss, grows daily worse and worse.” Worse … and worse? Jeez, Spenser, that’s the worst!). But “Said no one ever” goes further than Eco’s example of irony in that it gives the impression not of double-voicedness, exactly, but of a speaking voice and a silent, even nonexistent one. I’ve written about the rhetorical device occupatio before, and “said no one ever” seems to be a version of the kind of backwards ventriloquism whereby we say things by not saying them. This is no simple Barbara Cartland irony, in other words; this is Socratic irony all the way.

Now I’ll let Claire Colebrook explain:

“In being ironic, Socrates’ own position remains undisclosed… for in not saying what he means Socrates is able to remain above and beyond any content or dialogue, creating an absence or negativity, and not just something that is hidden. Perhaps Socrates is nothing other than his distance from received rhetoric. Perhaps there is no Socratic soul or self. If this were so, the Socratic ironic legacy would not lead to truth, recognition and moral education, but would leave us with a character, mask or persona that is ultimately enigmatic. Socrates would be more like a literary and created character, formed to question life, rather than one more person within life.”

“the ethic of philosophy is a distanced attitude toward any meaning. The philosopher recognizes the futility of any worldly value and in so doing produces herself as a philosopher in a turn away from the human.”

Strange as it might sound, I think the ironic voice behind the “said no one ever” meme—the voice that “speaks” as no one—creates just this kind of “absence or negativity,” this “mask or persona,” this “turn away from the human” that is also an invitation to the human to follow, and maybe redefine herself. How dreary, after all, to be somebody! Emily Dickinson was there to remind us way before someecards took over the internet:

I’m nobody! Who are you?Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us -don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know. How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

Here Dickinson gets dialogic in not too many more words than your typical “said no one ever” posting. How dreary to be somebody! It’s a lesson Agathon learns sharply, with Socrates as his pedagogue. It’s a lesson I hoped my students might learn from my assignment. But what I think I may have learned is that my students already learned this lesson, a long time ago; they didn’t need any help from me.

Still, I will continue thinking about how to improve my Getting Dialogic assignment. Steeped in irony as they are, first-year writers can still be awfully attached to the idea that writing is about inflexible rules instead of elastic conventions. Revision and translation assignments can break down this bias. And to conclude, finally, let me just say this: the conventions we use in academic essays have a lot to do with the conventions we adopt to define humanity. I’m no technological determinist, but I do believe in correlations between the criteria we use to define successful writing and the criteria we use to define successful people, governments, ideologies, etc. If we are taught to praise order and structure above all in writing and communication, we are more likely to praise these conventions in our systems, our relationships, our identities. But when we break these conventions, we open ourselves to new criteria for effective communication and, potentially, new behaviors, new value systems, new definitions for identity—including the enigmatic, snarky, sometimes obnoxious Socratic identity that allows us to speak as “no one.” And speak volumes.

**thanks to the following students for sharing their work: Alan Dong (Happiness word cloud), Shiv Patel (Intelligence infographic), Garrett McDaniel (video), Aileen Pollitzer (Love typography), Carlos Diaz (Justice typography), Jimmy Wang and friends (status update html), Anat Revai and friends (facebook video), David Moore (storify).