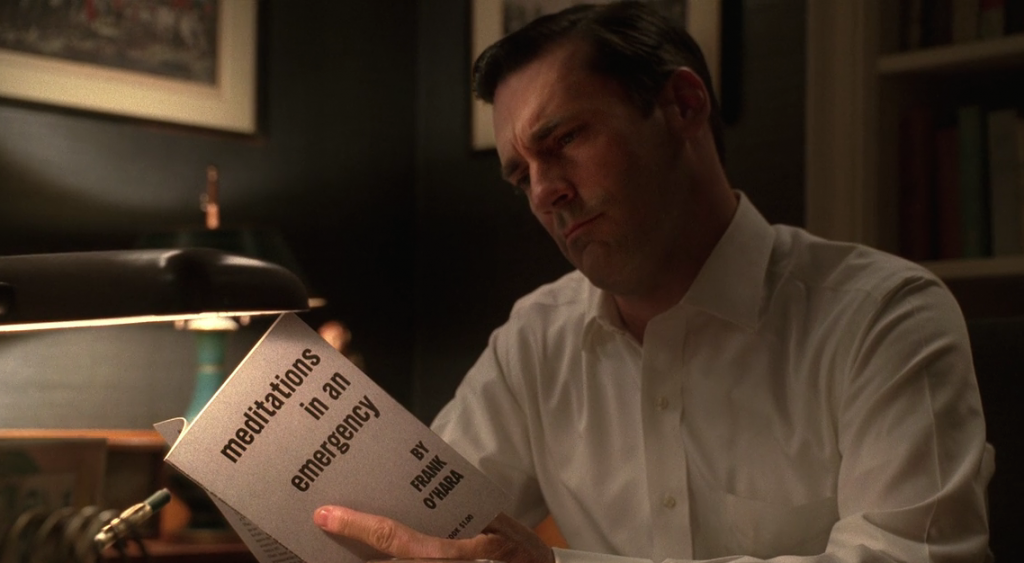

Don Draper, ad man, reads Frank O’Hara. Screen capture via Anna Ioanes.

The outcome of the 2016 presidential election has thrown a number of institutions into crisis––or at least deep soul-searching: the news media, the Electoral College, the Democratic Party, libraries, humanities departments, and the university more broadly. The first-year composition classroom, in particular, faces newly urgent pedagogical challenges in the wake of an election where irrational appeals to audience have defeated evidence-based arguments made according to the conventions of civil discourse. We teach rhetoric, which Aristotle defines as choosing the best “available means of persuasion” for a given circumstance (Book 1, Chapter 2). But in this moment, what does “best” mean? Can legitimate “means of persuasion” be unsupported by verifiable facts?

As the semester draws to a close and we consider how to approach not just the next academic term but the next presidential term, we have an opportunity to affirm our pedagogical commitments to critical thinking and rhetorical argument anew. These commitments are guided by a series of learning goals: we help our students learn to “judge factual claims and theories on the basis of evidence” and articulate “relationships among languages, philosophies, cultures, literature, ethics, or the arts.” We challenge students both to critique the arguments of others and to create arguments of their own, “in written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal modes, using concrete support and conventional language” (Georgia Tech General Education Outcomes). As scholars, we also have the opportunity and responsibility to fully explore the tensions between these pedagogical commitments and the world events that seem to challenge or undermine them.

To that end, the five authors in this essay each meditate on an immediate challenge in the writing classroom. The challenges described here relate to the role of politics in the composition classroom, the relationship between critical thinking and ethical citizenship, and the connections between argument and knowledge production more broadly. We write to express our opinions, which do not necessarily reflect those of the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“To Speak is Never Neutral”

My course this semester approaches composition through the theme of “Afterlives of Slavery,” and I designed it, in part, to give my students an opportunity to engage with “the issues” shaping their lives and to reckon with the ways argument is enmeshed in the stereotypes and material inequity we can trace to the “peculiar institution.” I believe that part of my responsibility as a teacher of writing and communication is to foster students’ understanding of themselves as participants in ongoing cultural conversations.

Thus, my classes often incorporate work from women’s studies, critical race theory, black feminism, and queer studies––bodies of knowledge with institutional power (however limited and under threat) that came into being through research, critical thinking, and evidence-based argument. These disciplines are not politically neutral but grounded in enacting social change. As political interventions into knowledge production, however, they also reveal that no intellectual discipline is neutral. To take an obvious example, the notion that an African American literature class is “biased” and an American literature class is “neutral” actually reveals the deeply biased (and even violent) way that the literary canon has been shaped by racist exclusion. (Moira Weigel offers a compelling history of “political correctness” that further illuminates these ideas.)

Even as my classes are fundamentally political, I have historically prided myself on my ability to remain “neutral” to my students. I’ve heard them tell me that they couldn’t figure out my political leanings. This was always surprising, but gratifying. I worry a lot about how to introduce my students to challenging new ideas without forcing those ideas down their throats; their sense that I am neutral makes me feel like I have succeeded. I suspect that I am not so opaque this semester, but not because I haven’t studiously avoided talking about the election. The very premise of my course––that racism exists, that representations have social consequences, that slavery is central to the American story––is incompatible with the preponderance of statements by the President-elect.

When I joined my students in the classroom after the election, I dedicated our time to their voices, insisting that their emotional and intellectual responses to the world belong in my classroom. Even if we, as educators, don’t have the right words to say, we can use our pedagogical and institutional power to show our students that their thoughts and feelings are not just legitimate but important. Real challenges exist: an open, student-centered conversation about the election means that grief-stricken students may be listening to their peers express indifference or happiness about the results. Even expressed respectfully, such statements can increase feelings of pain, betrayal, and outsider status. Students in crisis might feel afraid to speak or might feel that their pain or anger should be set aside in the “neutral” class discussion––or worse, that it’s a spectacle from which other students can learn. Questions arise: whose disagreement and discomfort do we recognize most easily? And whose discomfort or refusal should we be most concerned about? Which of our students are most comfortable expressing themselves, and how can we equip them to listen? And who is creating this space, anyway? Does the burden to facilitate such conversations fall disproportionately on the most precarious or overburdened faculty members? These questions are always present in classroom conversations about political and social issues, but the days after the election threw them into sharp relief.

Let’s set aside the inaccurate caricature of the “safe space” classroom as one in which students are sheltered from ideas that challenge or offend them: when we approach conversations about the election or other contentious topics as a neutral exchange in which each statement is intellectually and morally equivalent, we don’t just make some students feel more or less safe; we construct conversations that produce knowledge. An instructor who recedes into “neutrality” is hardly neutral in this circumstance. While I am committed to creating space for open conversation, I do not imagine such a practice to be neutral. I can add critical and resistant perspectives to that conversation, and I can keep affirming the humanity and dignity of all my students. I can speak, and more important, my students can speak.

- Anna Ioanes

On the Power of Bullshit

After the election of Donald Trump, educator David Tollerton questioned if the “practice of logical, reasoned argument itself” were now defunct. As composition instructors, we value logical argument; however, that value is now challenged, following the election of a man whose career has been characterized by lies and obfuscation. This fall, I have been teaching a course on “The Power of Truthiness: Thinking and Writing Empirically in a Post-Fact World.” After the election, the class has become even more strikingly relevant. While students in this course question whether human beings are persuaded by logic and empirical evidence or the “truthiness” of what feels true, I began with the assumption that “thinking and writing empirically” are necessary and useful in a “post-fact world.” However, like many others, I now question that assumption.

Tollerton states that ignoring the world of “cause-and-effect” only makes that world return with a vengeance. While I previously shared this belief, I no longer have his faith. Instead, I fear that the “subtle art of articulating effectual nonsense [may] be preferable to the ineffectual tools of argumentation.” As composition instructors, we’re taught (and teach) that rhetoric and logic are the backbones of the persuasive arts; however, if they no longer persuade, we need to consider the continued value of “thinking and writing empirically.”

Though I know that logic and evidence don’t always win, I have a firm belief in the power of bullshit. Bullshit is something I try to teach to my students: how it works, how to spot it, and how to combat it. During his campaign, Donald Trump was full of bullshit: that was part of his appeal to many people. At the Democratic National Convention, former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg called Trump’s campaign promise to “run the nation like he’s run his business” an obvious “con.” I wrote my thesis on nineteenth-century confidence men, so I also dabble in the art of bullshit. Teaching students to clearly recognize bullshit and how it convinces them despite themselves may be a potential path forward. At the very least, it gives me a direction that is not just reasserting a lost faith in the “ineffectual tools of argumentation.”

I am also trying another tactic: next spring I will teach a course focusing on narrative and empathy. The goal of the course is to teach students to be better writers and speakers as they use fictional narratives to understand our empathic relationship to others. In Trump’s America, using narrative and empathy may be more necessary than ever. While data about how much hate crimes are on the rise are interpretable in a number of ways, we do know that many of our most vulnerable citizens feel frightened and concerned about how much this country appears to hate and fear them. Bridging the understanding between people is one of our hardest acts as humans; I hope that understanding can be developed so that we won’t so easily fall prey to bullshit again.

- Owen Cantrell

Eroding the Border between Liberal (Arts) Pedagogy and Liberal Politics

Somewhere between Donald Trump’s rise to the GOP candidacy and his appointment of Betsy DeVos to the Department of Education, a line that many of us toe in the critical liberal arts classroom has begun to erode. This is the line that separates liberal arts pedagogy from liberal politics; the line that allows us to teach critical thinking and rhetorical analysis––what I would consider the basic tenets of liberal arts pedagogy––as something separable from teaching students to embrace liberal politics, become a liberal, or think like a liberal.

I’ve been sensitive to this ever-eroding line throughout the course of this election cycle. For me, its erosion has not been more evident than here, in my present attempts to describe it and articulate its presence in my classroom. In thinking about assignments that walk this line, I find myself wondering if these assignments and the ethos with which they are presented merely prove the point of Turning Point USA’s concerns. That is, instead of identifying and articulating this line, perhaps these assignments simply demonstrate the impossibility of defining the line at all, as liberal arts pedagogy is inseparable from the “advance[ment of] leftist propaganda in the classroom” (Professor Watchlist).

Let me be clear, here: the two sides to this line have always been interconnected. Indeed, “line” is an oversimplified metaphor for what is perhaps more akin to a web, a network, or a labyrinth. As many of us have noticed, lessons in critical thought and rhetorical analysis often lead students to (hypo)theses that could be characterized as politically liberal, even if this “political conversion” is not our pedagogical goal. This becomes particularly evident in lessons or assignments that challenge students to critically examine the discourses of race, gender, class, ability, nationality, religion or sexuality––what can more broadly be termed the discourses of identity––as they operate within the cultural systems of the United States. In my classroom, these examinations may look like any of the following examples:

- Guiding students to recognize the ways in which everyday language can perpetuate gender discrimination and structures of sexism through features like binary pronouns, the substitution of “man” or “mankind” for “human,” or the default position of “he” rather than “she” for a person of unknown gender, or a person in power.

- Prompting students to notice when women, people of color, or members of the LGBT+ community are left out of, demonized, or tokenized by popular television or film.

- Asking students to recognize the ways ideologies of exclusion determine access to various aspects of social or political life (like education in the relationship of public schools to housing districts), which renders the “American Dream” an exclusive ideal.

- Having students critically evaluate the cultural and historical contexts of phrases like “inner cities,” “thugs,” and “illegals,” so that they might develop a sensitivity to the racial and racist discourses that masquerade behind these “euphemisms.”

For students of the post-Trump classroom, the request that they critically think through their assumptions about American ideology as it is reflected in the country’s rhetoric seems no longer to be immediately or easily separable from requesting that they adopt a particular political stance. This is due, I think, to the role that public rhetoric––particularly around discourses of identity––played in this election cycle. Though always an important factor in voting (particularly within our bipartisan system, which ultimately boils down to winning the Electoral College), in this election cycle, public rhetoric and identity discourse as such have acted as delineating forces, separating red from blue states and determining the bottom line for many voters.

Consider, on the one hand, the “silent majority voters” who found themselves in need of change and saw that need met in Trump––in many cases, despite his unverifiable statements. In the pre- and post-election news cycles, these voters have found themselves in the position of defending their vote, of explaining that, for them, Trump’s exclusionary and inflammatory discourse along lines of race, nationality, gender, religion, sexuality, and ability, was something to be, if not always celebrated, certainly de-emphasized. On the other hand, consider those voters for whom Trump’s language articulated the very real danger he could pose for this country, in general, and, in particular, for those citizens who, due to their (racial, gendered, sexual, class, religious, national, ethnic) identity positions, are the least protected and most precarious in the United States.

Following the election, a person’s assignation of identity discourse and public rhetoric as of either central or peripheral importance is the most effective litmus test for determining political bias. We teach students how to think, not what to think. But in this political environment, can a faculty member still bring these issues to the center of the classroom, still hold students accountable for their own language and rhetoric, and still ask them to write and think in ways that are both critical and inclusive? Simply put, is it possible to do this without implicitly asking them to lean, vote, or think a bit more to the left?

In the post-Trump classroom, can liberal arts pedagogy be separable from liberal politics? If it cannot, then what has to give?

- Sarah Whitcomb Laiola

Rhetoric, Spectacle, and “Reality”

When Jennifer Forsthoefel and I first proposed the idea of teaching an English 1101 course about the 2016 presidential election in January, the reality of a President Donald J. Trump seemed far from likely. Though Nate Silver had Trump leading the Iowa Republican caucuses seven points ahead of Ted Cruz, with more significant leads in New Hampshire and South Carolina, the idea of a man once referred to by Andy Warhol as a “butch guy” and accused of rape in his first wife’s divorce deposition seemed too much like a plotline from The Simpsons or Back to the Future II (or, as I argue in a forthcoming article, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest) to be remotely grounded in plausibility. I have long been disillusioned with an electorate that would donate over $200,000 to the killer of an unarmed teenager or explode in fury over the most peaceful of protests. I was a vocal supporter of longtime Independent “socialist” Bernie Sanders, whose ascent in the ranks of the Democratic Party was no less perplexing in some circles than the emergence of our first (or second) reality TV candidate. And yet, I had a complacent faith that the American people would elect Hillary Clinton for the very same “business as usual” reasons that ended up costing her the election (though, of course, she won the popular vote by 2.5 million votes and counting).

The day of the election, Dr. Forsthoefel and I had assigned our students to read George Saunders’s reportage on the Trump campaign for The New Yorker, as well as a brief article exploring the relationship between reality television and governance. In retrospect, these reading assignments undoubtedly reflect a kind of smug denial of an imminent reality, suggesting a naïve awe at the very idea of a man supposedly kept up at night by the decision of whether or not to fire Gary Busey––an awe that has not lessened, but rather been drawn into sharper focus over the past weeks. The reality TV candidate is now the reality TV president-elect. In the midst of a transition so spectacular that not even Broadway has been spared a supporting role, now we have none other than European History Ph.D. Newt Gingrich telling The New York Times, apparently without irony, “In a lot of ways, what you’re seeing is the continuation of techniques and lessons [Trump] learned from doing what was, at one time, the No. 1 TV show.”

To say that I was disappointed by my students’ reactions to the outcome of the election upon returning to the classroom on November 10 would be nothing short of an understatement. Without a doubt, many of my students were openly affected by the news––especially my black, female, LGBT+, and international students, for good reason––and I suspect that many of them kept their emotional responses (whether positive or negative) closer to the vest. But for most of my students, November 10 came and went as any other Thursday; Trump’s victory seemed no more real to them than a particularly bloody episode of Game of Thrones. Aware of the pronouncement I had made during the semester’s first class––that this was a course about writing, not politics––I knew that it was wrong to attempt to force a reaction, to manufacture dissent. As a professor of political science and rhetoric once told me, “My job isn’t to make my students Democrats; my job is to make my students smarter.” But how are we to make our students smarter without drawing our students’ attention to the fact that what constitutes “smart” is, we have come to find out, negotiable?

One answer, perhaps, is to distinguish between the “reality” of “reality TV” and the reality of our current political situation. Dr. Forsthoefel and I titled our course “The Rhetoric and Spectacle of Presidential Politics,” and one of the unintended consequences has been an ongoing collapse of what is rhetoric and what is spectacle. Aristotle defines rhetoric as “the available means of persuasion.” In the end, red baseball caps, violent all-white rallies, misogynistic language, and a rhetorical style better suited to a 140-character limit than a mandate that one finish one’s sentences proved more available to Trump and more persuasive to (an Electoral College-defined segment of) the American populace than Clinton’s wealth of political experience, wonkish approach to policy, and arguments rooted in logos. “This is real, guys!” I’ve insisted so many times this semester, stopping short from warning my students that some of them may be deported, their names put on lists, or worse––proclamations too reminiscent of the tactics of the political movement that I have sought and seek to teach against.

Despite the extent to which reality TV is not reality and the extent to which Trump might continue to function as a kind of reality TV star via Twitter (and as an executive producer on The Celebrity Apprentice, though his starring role has been passed on to fellow bescandaled celbricrat Arnold Schwarzenegger), President-elect Trump’s power is far more real and abundant than Kim and Kanye’s. As Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen writes in the New York Review of Books, we have no reason not to believe that Trump will do everything that he has said that he will do (his selection of a Wall Street financier to the Department of the Treasury and a corporate CEO to the Department of State notwithstanding), and much of the power historically given to autocrats is handed over freely, sans resistance. Though this months-long election cycle has been drawn out, melodramatic, garrulous, and petty enough to deserve a primetime spot on Bravo, ours is a reality constructed by the American people, not Andy Cohen. If I can hope for anything to convince my students in the waning days of the fall semester, it is that though spectacle can be rhetoric, that doesn’t mean that it should be. President-elect Trump is no Hollywood fiction: we have no other channels to turn to, and even if we did, tuning out won’t make this reality go away.

- Andrew Marzoni

Affect Trumps Critique

I have spent the semester teaching mostly STEM students how to use critical theory in conjunction with multimodal rhetoric. In this course, critical theory was defined as a way to better understand literature (and other aspects of culture) by delving into historical, social, and ideological factors that influence the creation and interpretation of that literature. I have been both challenged and rewarded by working through the many expected and surprising uses of critical theory with students for whom these ideas might appear to layer another abstraction on top of the already difficult task of interpreting texts and culture.

My hope in designing the course was that seeing a range of interpretive possibilities would expand not just what my students think about and how to approach thought itself—but also how to consider the political consequences of interpretation. Further, I wanted students to better understand that the study of all texts—literature, popular culture, history, and rhetoric—has a disciplinary history similar to disciplines in the sciences.

Teaching students about what we came to call “critique” has required that I am not only prepared to discuss the wide applications of critical theory but also that I consider the gaps in theory—what theory is not designed to tell us about our experiences with texts. Students could only begin to see those gaps once they had used critical theory to explore our course texts. We read and discussed articles from a critical theory reader alongside a range of primary texts. Some students used frameworks that primarily focus on form, such as New Criticism and Structuralism, to discuss their affinities for (and frustrations with) Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906), a novel that has been largely understood through its formal failures. By the end of the semester, students created podcasts to present complimentary and competing interpretations of a wide range of texts—from OutKast’s Stankonia (2000) to George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road (2015). These projects turned my students into suspicious detectives: they analyzed texts with an eye toward the relations of power outlined by Marxism, feminism, postcolonialism, and critical race theory. In the last few weeks of the semester, we found ourselves discussing how a field born out of the political need to extend and multiply our thinking must react to an election that seemed to reject the very idea of cultural multiplicity.

Many of us would say that the work of the critical theorist is more important now than ever. Now is the time to dig in and reject the brand of nostalgic American nationalism that won out, albeit with an asterisk. I do not disagree.

My classes have concluded with a now-timely discussion about what critical theory might do in the future. The election results pushed us to discuss the interpretive possibilities that critique—or what Rita Felski (2015), by way of Paul Ricoeur, recently discussed through the “hermeneutics of suspicion”—does not allow for. Felski argues that “the barbed wire of suspicion” keeps readers in a defensive stance: “The critic advances holding a shield, scanning the horizon for possible assailants, fearful of being tricked or taken in. Locked into a cycle of punitive scrutiny and self-scrutiny, she cuts herself off from a swathe of intellectual and experimental possibilities” (12). For Felski, the hermeneutics of suspicion leave no room to understand our attachments to cultural objects outside a framework that assumes our pleasure in these texts is either a sign that they valiantly critique our society or, more likely, that we readers are falling prey to their nefarious ideological machinations. Our attachments abide, however, and they often function through affect, or the forces, which exist alongside but separate from conscious knowing, that move us toward feeling, belief, and action.

The neo-fascist language reverberating across the globe deserves our suspicion, and critiques of such language must continue to be heard. The question I find myself asking with my students, then, relates to what is not being heard. Namely, how can we communicate with a body politic that increasingly rejects the methods of critique in favor of a cultural and political narcissism that they often describe as enjoyment? Critique can tell us much about the Trump phenomenon, but perhaps we need to couple those methods with interpretive frameworks that explore the ways we enjoy texts we know to be bad for us. That is, without attention to the ways that readers identify with and attach to the texts they enjoy, we may well be left with students who can interrogate and analyze literature, film, and—perhaps most important of all—public rhetoric without a sense of how to explain the affective appeal of a charismatic autocrat. The point here is not that we teach students how to passively empathize with those who espouse racism, sexism, and a host of other unsavory political discourses, but rather that we expand our critical register in order to teach students how and why affect has trumped critique.

- Matthew Dischinger

Works Cited

Aristotle. Rhetoric. Retrieved December 7, 2016 from http://rhetoric.eserver.org/aristotle/rhet1-2.html

Felski, Rita. The Limits of Critique. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Irigaray, Luce. To Speak is Never Neutral. New York: Routledge, 2002.