College football is increasingly in the news, and usually for all of the wrong reasons. One of the most concerning things for educators is the relationship between the academic and athletic programs at our nation’s colleges and universities. And it is a tenuous, problematic relationship, undoubtedly. Imagine my surprise then when I found myself thinking of my pedagogy and the subject I teach–multimodal composition–through the lens of football. Taking a multimodal approach to teaching composition has given me an opportunity to reframe the way that I think about rhetoric, allowing me to think more holistically about the composition process and about argument. One result of that was the recognition that football is a venue of communication as much as it is a venue of athleticism; with that, I also began to see my classroom on the field.

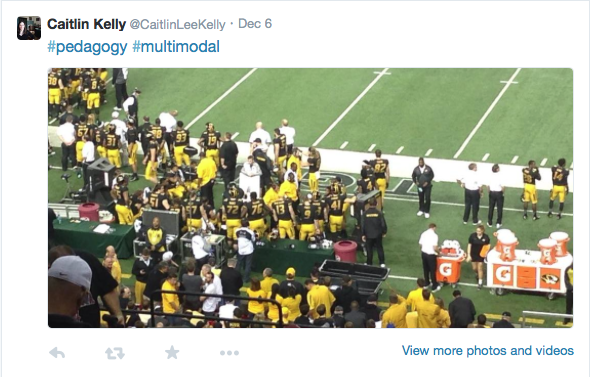

This picture was taken at the 2014 Southeastern Conference Championship Game at the Georgia Dome. In it, you see the sideline transformed into a classroom space, something I had never seen before in years of watching college football. This was the last place I ever expected to see a classroom take shape, but that it did. Moreover, I see my own classroom in that picture. One of the challenges with teaching literary texts is that talking about a written text can be an even more abstract experience than reading it. So, I get a lot of use out of the whiteboards in my classrooms, charting plots and sketching out scenes, for instance. More often than not, however, I invite my students to sit around the whiteboards doing that same work. So it struck me that the coaches were doing the same thing (using the visual mode) in order to help their students (the players) analyze their text (the football game). That common ground makes sense, of course. Not only does the giant whiteboard allow us to visual text–and in the case of football, movement–it invites us to revise when we encounter challenges. Just as a coach can demonstrate alternatives to a single play, students using whiteboards to make sense of literary texts can represent alternative interpretations with ease.

As I alluded to above, another place where I’ve seen a direct correlation between the writing classroom and the football field is in close reading and analysis. Successful athletes and coaches must be attentive to detail and able to observe their competition, then apply those observations in context, which is just what students in English classes do with literary texts. Both on and off the field, coaches and athletes analyze their opponents and interpret that data within the context of their own strengths and weaknesses. Coaches view practices and games high above the field in press boxes and they put that together with the view from the field that other coaches are getting. The best athletes can be seen on the sideline talking with the their teammates when they come off of the field, sharing what they have seen during the play. What is most remarkable is that this is all done during real time, unlike the close reading of texts. While we can always revisit a passage in a novel or poem, a football play is fleeting. In this way, analysis and interpretation is much more difficult when the text is a game (something that I imagine research on games and communication can speak to in fascinating ways).

Even more closely aligned with what we do in the multimodal composition classroom is the off-the-field study that football players do. In the film room (which often looks like a normal classroom), players analyze their text. They will watch an entire play or drive and then break it down, frame by frame, looking at the way that the parts of the play go together to produce it. In doing that, they are looking for the significance of the game as text: what it means for them as viewers and opponents. Then, there is the playbook that each player must study–a daunting task, and if you’ve seen a playbook, then you know what I mean. Learning its contents is challenging enough but the task of the player goes far beyond memorization, particularly for quarterbacks. Memorizing the plays is the first step: the hard part is learning to apply the right play under the right circumstances when the (rhetorical) situation is always changing. And not only does a quarterback have to know what play to call in any given context, he must translate it into a different mode, such as a nonverbal signal or an audible call; even if the coaches are calling the plays as is common at the college level, the quarterback still has to translate the call from visual or nonverbal cues coming from the sidelines.

Play calling in football is, in fact, highly multimodal, emphasizing nonverbal and visual modes of communication, something I only began to think about when I began to teach multimodal composition at Georgia Tech. It is also highly situational, and provides a model for the rhetorical situation, as can be seen in the way that BJ Kissel writes about audible play calling in the “Breaking Down the Art of the QB Audible.” As Kissel’s piece attests, play calling is often verbal, as when a quarterback uses a code word to signal the play before the snap. Most recently, NFL quarterback Peyton Manning of the Denver Broncos caused a storm with his use of the term “Omaha.” People demanded to know “What does it mean?” and “Why did he choose Omaha of all cities and words?” Though we don’t label them as such in popular media, these questions are actually about linguistics and rhetoric. For instance, as Brian Floyd points out, the use of the word “Omaha” isn’t unusual at all and that’s exactly why it works. To put it in rhetorical and linguistic terms, the signifier appears to be severed from the signified, and perhaps in some instances it is for everyone. The word “Omaha” has a different meaning for everyone involved: Manning’s offense, the defense they are facing, and, us, the fans.

Aside from the oral mode, nonverbal/gestural cues and visual cues are increasingly frequent methods of communicating plays from the sidelines. Audible calls and gestures are the older methods that we are probably all most familiar. However, it has been visual play calling that has garnered the most interest and attention. Chip Kelly, coach of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles, and then Gus Malzahn, coach at Auburn University, have pioneered a method of visual play calling that employs images of pop culture icons and symbols on large posters. As many sportswriters and fans have pointed out, these signs are as entertaining as they are effective. However, for composition teachers and scholars, it’s worth digging into why that is. Again, it comes down to the intentional separation of the signifier and signified; an image of a pop culture personality is funny because it is taken so far out of context, and while we might not be privy to that new context, we enjoy the game of trying to figure out the new meaning and how it relates to the old context. Also part of the entertainment and effectiveness equation is the way that visual images relate to movement. As Gabe Zaldivar explains, the signs are chock full of meaning, conveying spatial formations and movement within them in a “system that renders the huddle nearly obsolete.” In a multimodal approach to teaching composition, this method of play calling becomes a prime example of the way that a careful consideration of a mode’s affordances (here, the efficiency of images to communicate a complex set of information) can maximize effectiveness.

Thinking of these parallels between football and what we do in the writing classroom leaves me wondering how football inspired activities could be integrated into my classes. I haven’t tried these yet but here are some ideas that I’ve made a note of this season:

- Invite students to create placards like those Chip Kelly pioneered. They could simply write messages to one another using drawings and images found online, or, in a literature based course, encourage them to compose the signs from the perspective of different characters.

- Get students moving by asking them to design some nonverbal signs. Those signs could be used to facilitate discussion.

- Try running a discussion where groups of students communicate through code words, perhaps in a debate.

So, whether you are counting down the days to the start of the 2015 football season out of excitement or dread, you might consider how football relates to your own pedagogy and if you can draw connections between the two in your classroom. And, for those of us teaching at Georgia Tech, well, we can even try these lessons out in the shadow of John Heisman himself.

About the Author:

Caitlin L. Kelly (PhD in English, University of Missouri; MA in English, University of Tennessee) has been a Brittain Fellow since Fall 2013. Her research area is 18th-century/Romantic-era British literature and culture, with particular interests in religious and print cultures and the development of the novel. She is also an avid sports fan–especially MLB, MLS, college football, and track and field. Follow her on Twitter at @CaitlinLeeKelly or email her at caitlin.kelly@lmc.gatech.edu.