On the Oculus Rift and using VR in the classroom.

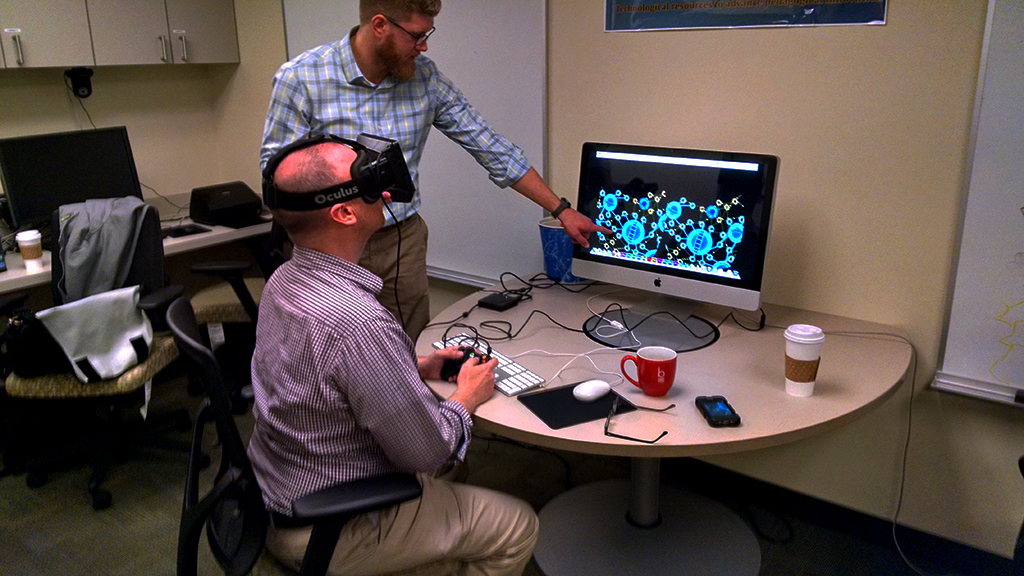

On October 22, 2014, Stephen Addcox and Joshua Hussey conducted a demonstration of the Oculus Rift (DevKit 1).

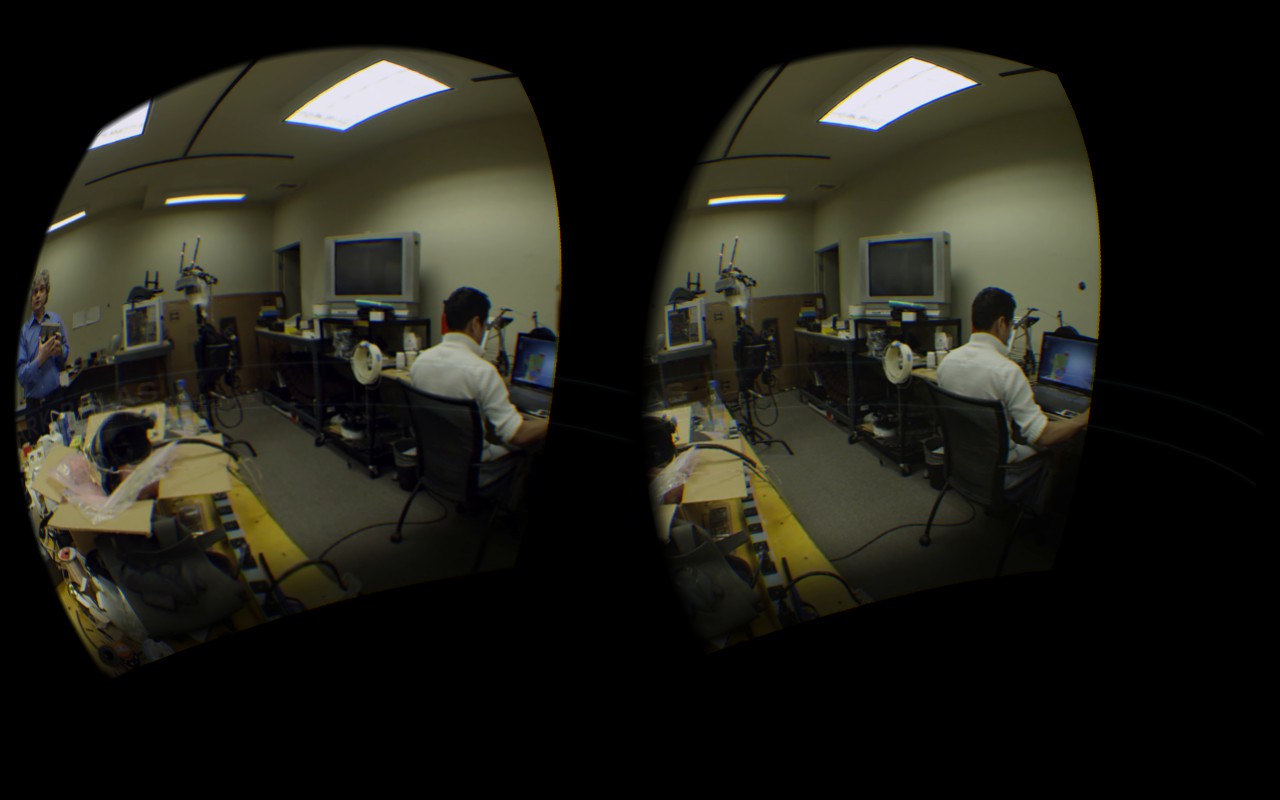

(In the darkened space of DevLab, Eric Rettberg, Stephen Addcox, Nicole Lobdell, and Joshua Hussey take turns stepping into augmented realities through the Oculus Rift headset. NP: Jon Kotchian, Julia Smith, Andy Frazee.)

When Dr. Stephen Addcox and I were developing tutorials for demonstrating the Oculus Rift, we attempted to consider its pedagogical possibilities. What issues of purpose might be attached to the study of the device in the classroom? Outside of its consumer potentials, who cares about the Oculus Rift and VR in education? If the Oculus is a true development kit, what kinds of content would be useful or even available? And while the DK2 is reasonably priced for developers at $350, it would be impossible to furnish an entire classroom with them.

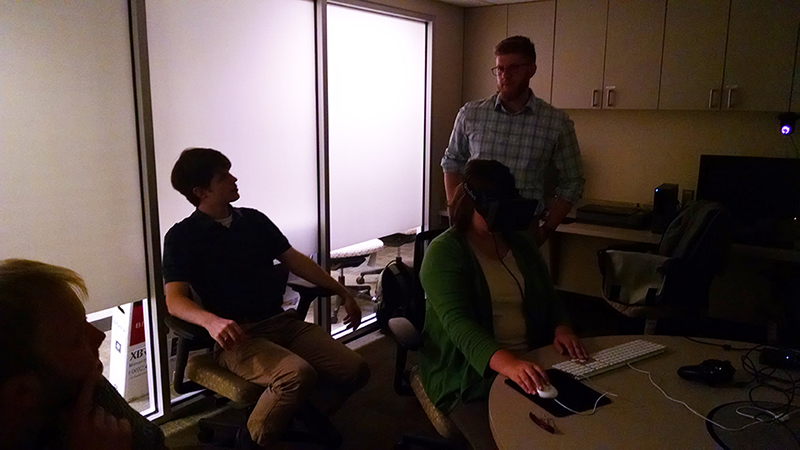

(Brown shaders: The Oculus World Demo lets a player explore a Tuscan-styled villa.)

(Eric Rettberg looks left as he traverses some virtual grassy terrain.)

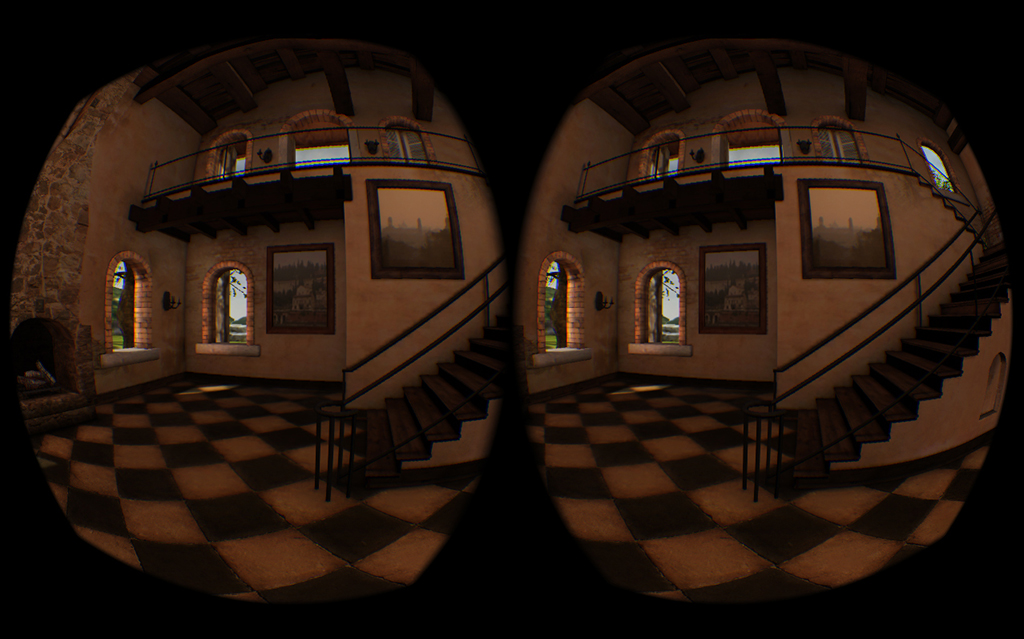

Conceptual and Practical Dev: So, what are the parameters for development if the technology isn’t entirely ready for mass consumption? Palmer Luckey, in Condition One’s film Zero Point, exclusively for the Oculus Rift, says that “It is Day Zero for Virtual Reality, and consumer access is finally possible.” While access is certainly possible, complete (i.e. longer) content remains unavailable, mostly because projects are still in development and will take some time before they are ready for the demands of the entertainment-hungry masses. At the same time however, it feels like there is some kind of hesitation with the technology: is it a medium or a peripheral? Sony’s VR philosophy addresses that “open” issue, if only to confirm that games and gaming “are only one kind of content” and there are no genre requirements. Their product, the Morpheus, [which] competes with the Oculus certainly, and integrates with PlayStation Move devices in order to facilitate more immersive play beyond the headset.

(Sony’s Morpheus.)

(From Sony’s “Future of Innovation” PlayStation event at the Games Developer Conference 2014, as reported by theverge.com.)

(Joshua Hussey directs Andy Frazee in a demo of Darknet, a game about hacking. The demo begins by announcing, “Welcome to Cyberspace. You have been contracted to install a logic bomb in a secure network.”)

Understanding that gameplay was only one type of content, we explored other possibilities of a VR headset’s potentials. One could curate museum spaces surely, where visitors would be able to navigate those spaces and have access to art they might normally never experience. Those types of experiences follow along with Sony’s philosophy that “VR is a medium, not a peripheral” and the socially-empowered notion that, “It is for everyone.”

If spaces can be curated and entered much like a proper-world museum, then we could foreseeably travel to any part of the globe to not simply take in the sights, like Google Earth or Wii U’s Panorama View permit us peripherally, but to actively sense places and objects in three-dimensional locations with size, scale, and texture. The process for creating these realistic artifacts is, of course, incredibly time and resource-consuming, so we may have to wait a while until we can navigate the structures of the Pompidou.

Considering still how VR could be used in pedagogical circumstances, Dr. Andy Frazee offered up an idea to create a VR-inspired class archive. Using techniques of photogrammetry (which uses photographs to create 3D positions), one could curate artifacts created in the LMC’s composition course series. Much like the Arts Initiative’s Student View, these artifacts might be juried and then exhibited in digital spaces that could be “visited” through the program’s VR headsets.

(Video of a 3D model of Horatio Nelson bust in Monmouth Museum, Wales, produced using photogrammetry; From Wikipedia)

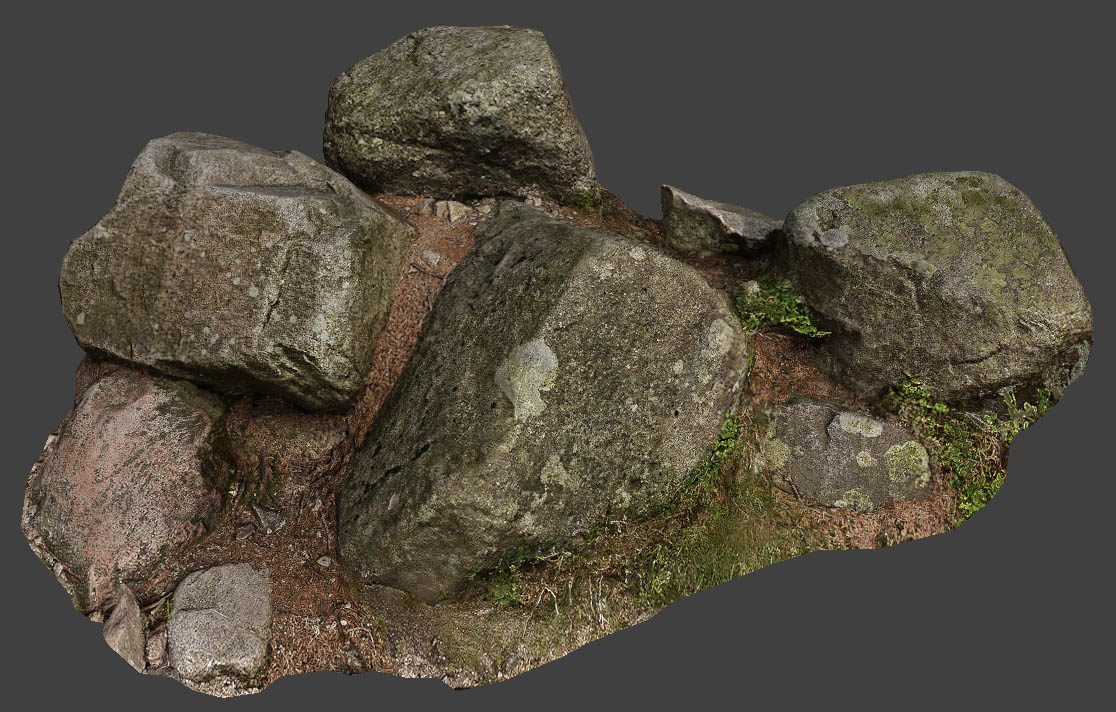

While resolution quality remains on the low end for mass consumption, the DK1 and DK2 kits [specs here] demonstrate the early stages of good looking picture. Producing realistic models of art with photogrammetry techniques takes time and resource commitments. Game developers The Astronauts depended on this technique recently for their 2014 adventure game, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter to present highly-detailed objects and models in their narrative puzzler. Their blogpost on the process demonstrates the methods of translating real-world objects into virtual ones.

(Nice rocks! A final asset from The Vanishing of Ethan Carter. Image: Poznanski, Andrzej. “The Visual Revolution of the Vanishing of Ethan Carter.” theastronauts.com. 25 March 2014.)

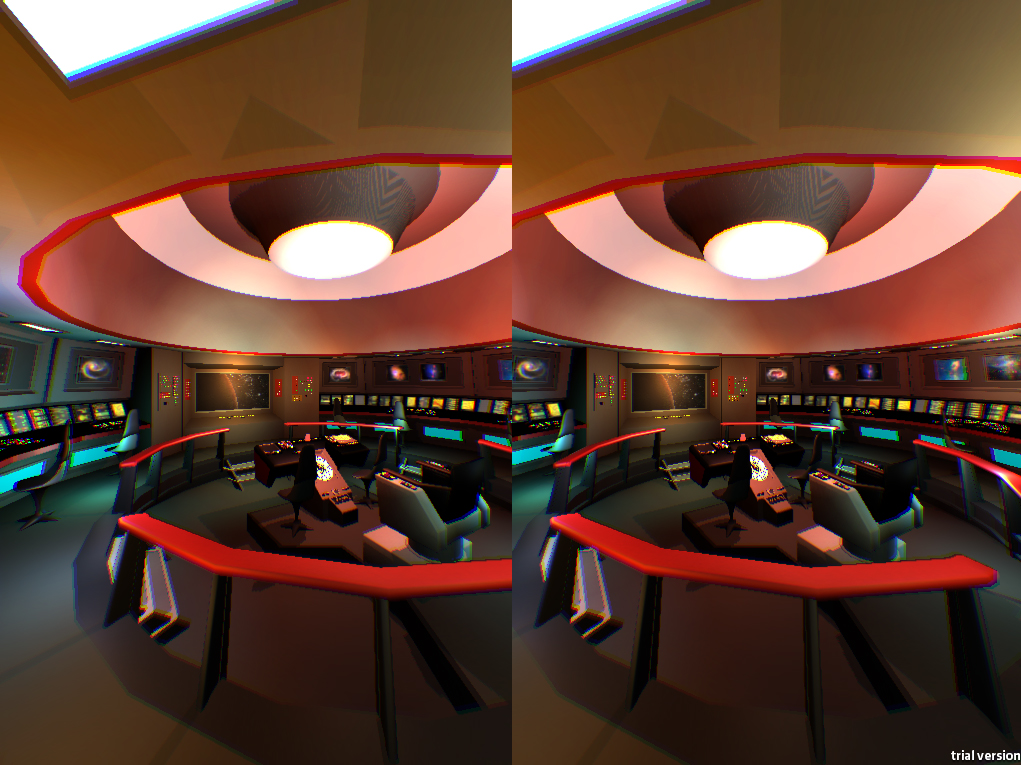

(Stephen Addcox is very excited to visit the bridge of the Enterprise in this non-game exploration of virtual space.)

(Bridge exploration in Enda O’Connor’s The Bridge of the Enterprise. http://endaoconnor.com/)

Film is yet another obvious content type for VR. Jaunt, helmed by Jens Christensen, Tom Annau, and Arthur Van Hoff, are creators of the VR camera of the same name who claim to be, and mostly likely are, setting the standard for VR content quality. All three carry advanced degrees in CS and Computational Neuroscience, and their eclectic board of advisors includes director Mark Romanek (and James Cameron as the rumor goes).

As a medium, as a social experience: Ben Kuchera of Polygon reports his teleportation experiences after viewing Jaunt videos taken from a concert, a club show, and a boxing match where half the time he absorbs himself in observing the people in the crowds, describing himself as an acting “ghost” that could zoom in on the minute detail of a person’s behavior: “It’s a pure experience, repeatable and explorable” he writes.

(Jaunt cameras. Images from Techcrunch and Polygon.)

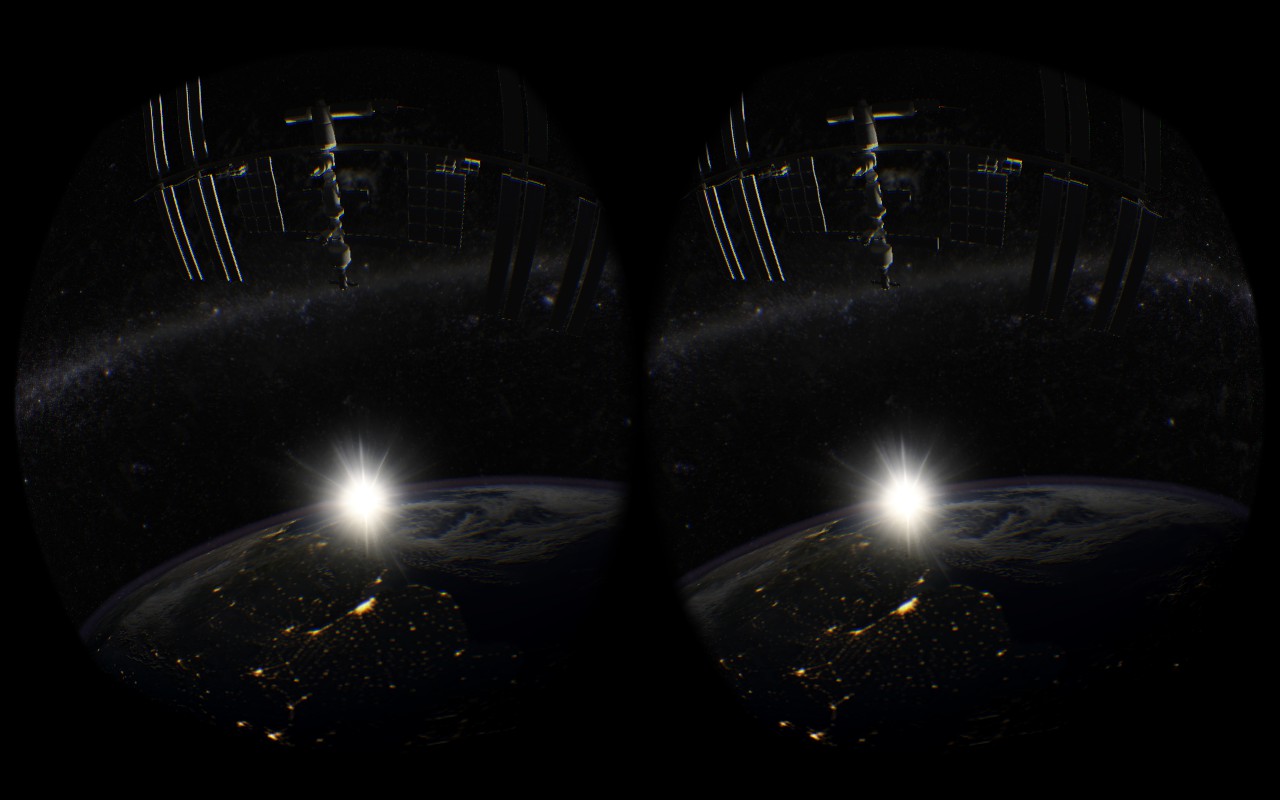

Zero Point, Condition One’s film for the Oculus Rift released through Steam on October 28, represents the very first 3D 360-degree film. Observers are moderate passives during the film: one can look around any of the environments but can’t move around in them. The experience remains highly immersive even in the absence of user mobility: content is not a game, but rather a mix of documentary film and scenic travel. Nevertheless, the experience generates significant emotional responses because of the user’s absorption into exceptionally realistic multi-dimensional space (“Emotion is Amplified”).

(Inside Zero Point. In-movie screenshots by Joshua Hussey.)

Some final thoughts. Thinking, finally, on development potentials, I’m reminded of Janet Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck (1997). In her address of humanity’s fear of new mediums of artistic expression and communication, she offers two takes on virtualized experience: the holonovel of Star Trek, which is continuous with the larger tradition of storytelling, stretching from the heroic bards through the nineteenth-century novelists,” and Huxley’s “feely” from Brave New World, which in its destruction of meaning and fragmentation “implies the death of the great traditions of humanism” (26). Murray continues, reminding us that fiction, regardless of its medium, tells us what it means to be human, and that eventually, the technologies with which we tell and receive stories become “transparent” and “we lose consciousness of the medium and see … only the power of the story itself.”

(Tiled Oculi: Drs. Jon Kotchian, Joshua Hussey, Andy Frazee, Stephen Addcox, Eric Rettberg, and Nicole Lobdell show you the coming-future of VR addiction.)