I recently read Cathy Davidson’s “Let’s Talk about MOOC (online) Education–And Also About Massively Outdated Traditional Education (MOTEs)” on the HASTAC [the Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Advanced Collaboratory] blog. I agree with her argument that talking heads do not a MOOC make (nor do they help digital pedagogy in general). I particularly like her use of the verb “squander”: using talking heads (a form of MOTEs) is “squandering a technology, not taking advantage of its particular affordances that cannot be duplicated elsewhere in the analog, pre-digital world.”

The Gatekeeper Syndrome

Yet I’m worried that an even more basic issue, what I call the “gatekeeper syndrome,” hasn’t been fully explicated in discussions of MOOCs and digital academia. The gatekeeper syndrome is most often exhibited in MOTE classrooms, and it is responsible for some of the mistaken and prejudiced thinking about digital pedagogy and the digital humanities infecting academia today. The gatekeeper syndrome has many symptoms, usually expressed in the rejection of democratic pedagogy / active learning, and in the rejection of digital and hybrid pedagogy.

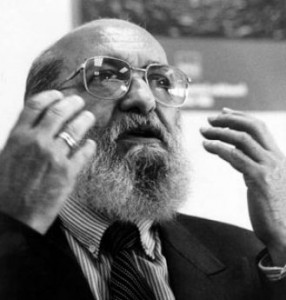

I’m worried that there are college professors—some surprisingly young—who have never heard of democratic pedagogy and who think that its progenitor, Paulo Freire, is a mildly spicy casserole. They have been trained in a system which privileges the power dynamic of the banking system of education, and which privileges the professor as the knower beneficently giving knowledge to the unknowing. These professors have been trained to see themselves as gatekeepers in the “closed system” of knowledge. As Davidson has argued elsewhere, this gatekeeping is trained into professors by traditional collegial practice. The training becomes a repetitive cycle that needs to be broken, and one way to do so is by changing the way we teach.

Democratic pedagogy begins with the idea that teachers do not pour knowledge into students. It holds, to use Freire’s famous metaphor, that students are not banks into which teachers deposit knowledge. He called this practice the banking method of education because it presumed that all of the power of knowledge was in the teacher’s / owner’s hands and that their job was to deposit that knowledge into the piggy-blank slots in the top of their students’ heads. But this method, Freire argued, does little to develop learners’ agency and democratic participation (you know, the reasons why we teach). Instead, he suggested, teachers should find ways to facilitate sharing and building knowledge between students.

Gatekeeping is a Virus

Sometimes, the gatekeeper syndrome is particularly virulent when professors who resist democratic pedagogy also resist digital pedagogy, or teaching using digital tools for creation, dissemination, and evaluation of student work. Surely, not all teachers who reject democratic pedagogy also reject digital pedagogy. (I myself resisted digital pedagogy because I wasn’t sure how I could make it democratic), but the one creates a favorable environment for the other. It doesn’t surprise me now that some of the same teachers who resist giving up the lecture format are also those who resist using digital tools. Davidson and others speak to this very hot mess when they note that professors’ attempts to transfer their classes verbatim don’t work. Active learning, discussion, interaction, reading, and processing together work.

A key to protecting against the gatekeeper syndrome is to figure out who we are as teachers and what we do with information. If we become our best selves as teachers, the technology will follow. This conversation reached a high pitch at a recent THATCamp in discussions of the gatekeepers’ preference for paper objects, the religious objects of academia. These have been imbued with power—a power that more senior professors, hiring committees, and publishers access to translate or to share with younger colleagues and students. They do not see digital publishing, scholarship, or pedagogy as potentially transformative and democratizing power. Instead, those suffering from the gatekeeper syndrome see it as a dangerous power that will unleash chaos. The knowledge will erupt uncontrollably and we’ll all slide into the maw of the USWeekly beast.

Best Practices

Maybe we will slide into the ugly maw. But that won’t be digital pedagogy’s fault. The point is that the gatekeeper syndrome contributes to the problems we’re currently facing in academia. We can fight it, however, if we reflect on ourselves as teachers (and learners) in highly fluid educational and intellectual situations, and remember a few things:

1. Realize that our power as teachers doesn’t go away when we “give” knowledge away. Our power rests in other things, such as the ability to provide feedback on student work, to practice good assignment design, and to facilitate our students’ communal efforts at building knowledge.

2. Having made it safely through the gate does not entitle or compel us to take up punitive gatekeeping. Instead, consider practicing a generative kind of gatekeeping that builds and shares knowledge across platforms. This does not mean that there should not be standards by which we measure progress (of our students or colleagues). Instead, it means we should recognize that the old standards and methods are doing more damage than good.

3. Calm down, the tech won’t bite you. Unlike before, when computers were huge and hugely expensive, mistakes might have been very, very bad. But now, many things that go wrong with digital technology are fixable, work-around-able, or google-able. Fortunately, there are more and more people willing to share their expertise. Breathe and try this new thing once, and try this other thing again.

I hope this generates conversation; I hope to be back soon with a follow-up of this post and an end-of-semester wrap-up for the column.

Really, really like this. We need a movement against MOTE.

Thank you very much! There has been a quiet movement for a long time, but we could possibly be louder about it.