Introduction

For many teachers, the following “Syllabus Day” template might sound familiar:

Introductions. Syllabus. Course calendar. Please mask up for class. Any questions? No? All right, email me if anything comes up. Looking forward to working with you this semester. Have a great day!

There is nothing inherently wrong with having a first day function like this; we do have to review the syllabus and its policies with the students to make sure they understand what we, the program, and the university expect of them in terms of learning and labor. We want to have a shared vision of our semester as we move into the meat of the course. We want to make sure people know what plagiarism is and whether they can submit late work and why we do or do not have an attendance policy. The problem is that if everyone’s first day of class looks similar to this template, how might it feel to be a student living through five such “syllabus days” in the first week of every semester? And by the time they graduate they’ll have endured roughly 40-50 of them. Imagine: 40-50 class periods spent doing the exact. Same. Thing.

As I tell my Technical Communication students, we are not obligated to accept templates in their entirety. Templates provide structures around which we build with the flesh of innovation. For instructors, the “Syllabus Day” template is no different. The first day of class is an opportunity for instructors to set the tone for an engaging semester-long learning experience; in this course, students will learn about course material by learning from one another. For some instructors, syllabus-oriented activities can be one effective way to encourage students to engage with the course content, while introduction activities can help students engage with each other as members of a learning community. When combining these two purposes, first-day-of-class activities, planned and executed well, can make our “Syllabus Day” dynamic and different. It will (hopefully) capture students’ attention and put them on the path toward meeting our learning outcomes.

Introducing Ourselves

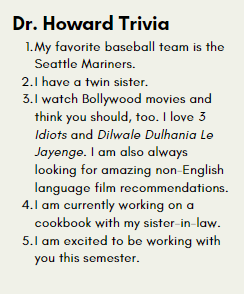

Over the years, I have consistently sought to communicate my desire to get to know students as individuals rather than faces in the crowd. One of my methods involves introducing myself to my students on “Syllabus Day” to show that I am both their instructor and a human being. Kevin Steele, a director of instructional technology at Valparaiso University, writes, “Authentically introduce yourself to the students at the very start of class. Spend a bit more time on it than just your name and title…. Keep it short, but show you are a real person, too. Your introduction will make you personable, approachable, and interesting to your new students.” Not only do I seek to do this on the first day of class, but I have also begun including facts about myself in my course syllabi, referring to my media preferences or favorite sports teams. I also have a smiling headshot of myself in my syllabus (a recommendation made by some of my Technical Communication students last semester). Such information can help to frame not just the class as a welcoming and friendly learning environment, but also me, the instructor, as someone who is interested in fostering that environment and connecting with the students.

Over the years, I have consistently sought to communicate my desire to get to know students as individuals rather than faces in the crowd. One of my methods involves introducing myself to my students on “Syllabus Day” to show that I am both their instructor and a human being. Kevin Steele, a director of instructional technology at Valparaiso University, writes, “Authentically introduce yourself to the students at the very start of class. Spend a bit more time on it than just your name and title…. Keep it short, but show you are a real person, too. Your introduction will make you personable, approachable, and interesting to your new students.” Not only do I seek to do this on the first day of class, but I have also begun including facts about myself in my course syllabi, referring to my media preferences or favorite sports teams. I also have a smiling headshot of myself in my syllabus (a recommendation made by some of my Technical Communication students last semester). Such information can help to frame not just the class as a welcoming and friendly learning environment, but also me, the instructor, as someone who is interested in fostering that environment and connecting with the students.

Learning Students’ Names

Trying to learn students’ names on the first day of class, like teacher introductions, is yet another way to signal our interest in treating students as individuals and building relationships of trust with them. When I arrived at Georgia Tech, the former program director, Dr. Rebecca Burnett, emphasized early and often the importance of learning our students’ names. In our English courses at Georgia Tech, Brittain Fellows are teaching fewer students than many other faculty on campus, although we might and do argue that our course caps remain too high, given the nature of our subject matter and assessment processes, our position within the university ecosystem, and our overall purpose as faculty in the Writing and Communication Program. Smaller course sizes allow Brittain Fellows to make more profound connections with their students, and introduction activities and name-learning on the first day can be crucial for cultivating those connections from the outset of the semester. While I have found that I can remember students’ names simply by taking attendance or by reading, reviewing, and remarking upon their work, by having quality introduction activities on the first day of class, I have discovered that the process of learning students’ names becomes much faster and easier. Furthermore, the sooner we can start addressing students by name, the better for our classroom environment as students begin to feel seen, heard, and known.

Past Introduction Activities

Over the years, I have experimented with different “Syllabus Day” activities, mostly expanding on the “name, hometown, major” schema. Of these, many have worked fine in helping me get to know my students, learn their names, and begin to establish rapport. During one period of my career, I, as a lapsed eighteenth-centuryist and Jane Austen fanboy, consistently used an introduction activity adapted from game played in Austen’s Emma. During an outing to Box Hill, Frank Churchill says,

“Ladies and gentlemen—I am ordered by Miss Woodhouse to say, that she waives her right of knowing exactly what you may all be thinking of, and only requires something very entertaining from each of you, in a general way. Here are seven of you, besides myself, (who, she is pleased to say, am very entertaining already,) and she only demands from each of you either one thing very clever, be it prose or verse, original or repeated—or two things moderately clever—or three things very dull indeed, and she engages to laugh heartily at them all.”

In my activity, in addition to the usual fare of “name, hometown, major,” my students had to mention a) one fact about themselves that was extremely interesting, b) two facts that were moderately interesting, or c) three facts that were “very dull indeed.” Students frequently defaulted to a combination of options a) and b), namely only providing one fact about themselves that was moderately interesting, but the activity did elicit a lot of sharing and connection among athletes, people who attended the same or rival high schools, and musicians.

Later, I added a component to this iteration of the activity in which I repeated people’s names after they gave their “facts,” and every 4-5 people (approximately) had to say the names of everyone who had introduced themselves up to that point. This method allowed me to learn the names of every student by the end of Day 1, and I only needed a bit of reinforcement to commit those names to long-term memory by the end of the week.

While there was plenty of name-learning and engagement among students as people, I also wanted a First-Day-of-Class activity that did more than this “name, hometown, major” supplied. For my own pedagogical purposes, this version of the activity didn’t do enough work to engage students with the course content, so I wanted to develop something that did.

Current Introduction Activity

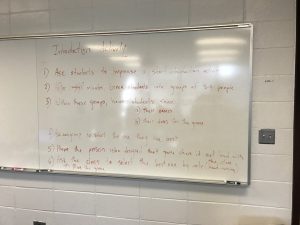

The whiteboard instructions for playing the introduction activity described in the article in which students produce instructions for their own introduction activity.

In my Technical Communication course this semester, I turned the time over to the students on Syllabus Day, letting them decide how we would introduce ourselves to each other. I asked them to present their own introduction activity to take the place of the “name, hometown, major” ones that all these upper-division students had lived through in their academic careers at Georgia Tech. In this activity, students designed instructions, using standard conventions such as numbered steps, for an exciting array of games we could have played.

Because it was a Technical Communication course, I saw an opportunity to get students talking to others in their budding community; we were also beginning to frame the work we will be doing in class around a primary characteristic of technical communication, which, according to the Society of Technical Communicators, includes “providing instructions about how to do something, regardless of how technical the task is or even if technology is used to create or distribute that communication.” (“Defining Technical Communication”).

Their work was both exciting because of their creativity and tragic because we did not have enough time to play all the games. Some of the games resembled the “name, hometown, major” schema I had been trying to move away from, but they were still different and fun. Most of the students did their best to be conceptually ambitious with the task and made the game something they personally would enjoy playing. Here are some examples: [1]

Example 1 (Zoe) [2]

- Everyone gathers in a circle.

- One person is picked from the circle to start the game.

- The person chosen to start the game must come up with a verb or activity that starts with the same letter as their name, for example: someone named Jenna can choose the verb “jumping.”

- While performing the action picked, the person will say the name of the action and then their name. For example, Jenna will jump up and down and say the words “jumping Jenna.”

- Whoever is to the right of the person who started the game must do the action and say the name of the starting person, then tack on their own name and action. For example, this person will say “Jumping Jenna” while jumping, and then say “Dancing Daniel” while dancing.

- This will continue until the last person in the circle is forced to remember all of the names and actions of the people in the circle.

Example 2 (Vincent)

- On a standard sheet of paper, write the following information:

- Your name, major, and year

- Expectations you had of college when you first entered

- A reflection on the reality of these expectations (e.g. did your expectations come true?)

- Crumple the paper into a ball

- Have everyone throw their balls into a designated area of the room (e.g. a corner)

- One by one, have a student walk to the corner and pick up a random ball. If this student picks up their own ball, have them pick up a different ball to read. The student will read the sentences written on the ball to the class. They will read the name at the end.

- The student whose ball is read will stand up to be acknowledged, then be the next person to walk up and read a ball.

Ultimately, we played an introduction game with a heist theme.

The whiteboard list with the different roles described in Maya’s game: distraction, hitman, getaway driver, mastermind, and hacker.

Example 3 (Maya)

- Split the class into groups of 3-5.

- Present the background of the activity: Heist! Imagine you and your group have to break into a bank. Based on each group member’s personality and interests, divide your group into roles: the distraction, the hit man, the mastermind, the hacker, and the getaway driver.

- For each group, present to the rest of the class which roles you assigned your team members and give a brief explanation why.

As we started to play the game, different people asked questions to clarify what they needed to do, and we made some small modifications as needed. This allowed us to talk about and model how testing and evaluating technical documents improves future iterations by augmenting usability. It also set the stage for talking about user experience and data and the ways in which collecting and acting on that information can lead to more effective technical documents. Finally, our introduction activity also signaled to the students that this course is a creative and collaborative space and that I expect them to work together in groups. All these things will come up in later readings and discussions, but we were able to start foreshadowing these concepts from the outset of the semester through this activity.

Conclusion

Ultimately, I would argue that “Syllabus Day” is much more important than some instructors and students recognize, and we probably ought to be doing more with it (if we aren’t already) so students do not treat it is unimportant. Yes, students need to understand our course policies and outcomes and themes, but we can cover all of that and still have time for a class period in which students start to engage effectively with the course’s content and build community among themselves and with their instructors both. If we move toward maximizing the way we frame the first day of class, then impactful learning and relationships can start to develop, even if it is just “Syllabus Day.”

[1] A big thanks to the students, Zoe, Vincent, and Maya, who allowed me to include their work in this article.

[2] Zoe told me that she first played this game on an (Outdoor Recreation Georgia Tech) freshman orientation trip, and said, ”I also was known as zig-zag Zoe for the rest of the trip!”

If you are interested in learning more about the work that Brittain Fellows are doing in Technical Communication courses at Georgia Tech, feel free to read the two-part article “Students, not Consumers: Rethinking Our Assignment Sheet Design” by Jill Fennell and Jeffrey Howard and “Rethinking Instructional Scaffolding” a three-part article about ethics training modules written by Jonathan Shelley and Dori Coblentz.