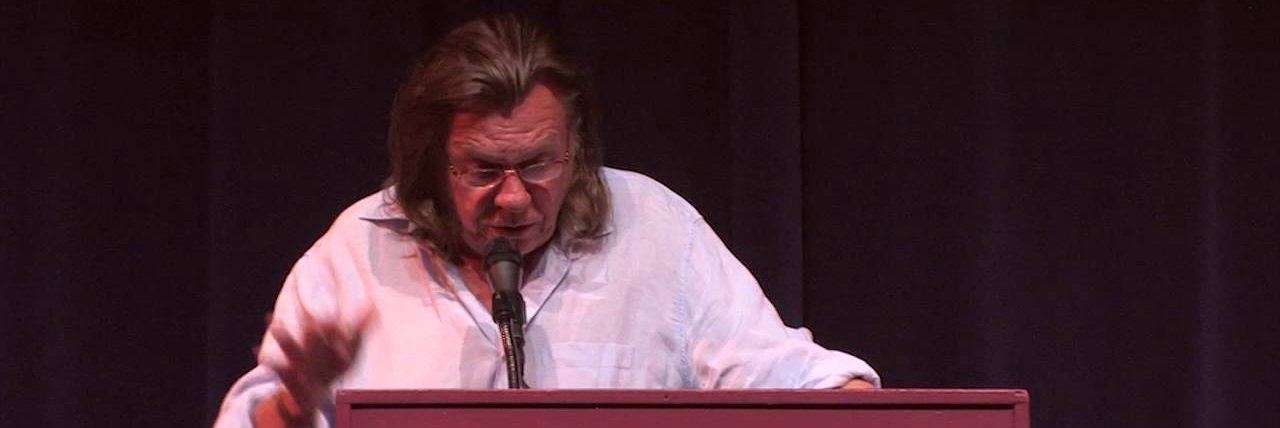

Thomas Lux reads his poem “Ode to the Fat Child” at the Palm Beach Poetry Festival in 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L00hSdpt6O8

Editor’s Note: When I first had the idea to teach an English 1102 course about the The New Yorker magazine, I had hoped that Thomas Lux, who has published five poems in the magazine, would come speak to my students. Vijay Seshadri, former editor at The New Yorker and frequent contributor to the magazine, was scheduled to read alongside Lux at an event hosted by Poetry@Tech, a program founded by Lux in 2002, which (along with the Writing and Communication Program) awarded me a pedagogy grant to incorporate poetry into my 1102 course this spring. I emailed Lux just after Christmas about the idea of him and Seshadri visiting my class together. He wrote me back two days later: “Andrew, Not only does the Brit/ P&T collaboration put the few bucks in Brits’ pockets but it is pedagogically sound! Most fun (he was my student) would be both of us on Wed or Fri. Good idea. I’ll see what works best for him. Tom.”

Lux passed away this February, and though it’s a shame that my students weren’t to have the pleasure of meeting him face to face, they encountered him in the same way that most of his devotees have: through his poems. My students got to know Lux by reading his contributions to The New Yorker as well as the work of poets who influenced him, watching the wealth of video recordings of Lux reading and discussing his poetry available online, and attending Poetry@Tech’s Tribute to Thomas Lux on April 23, where poets included Edward Hirsch, Stephen Dobyns, Stuart Dischell, David Bottoms, and Ginger Murchison celebrated Lux through personal remembrances and readings of his poems. As one of the final assignments for the class, culminating a unit on poetry and criticism (I organized my syllabus by genre, following the order prescribed by the magazine’s table of contents), I asked my students to write a profile of Lux’s career in the style of The New Yorker‘s “Books” section. The following essay, by Alec Reinhardt (which he graciously allowed TECHStyle to publish), is the strongest of the bunch. — Andrew Marzoni

It is a familiar cliché in comedy that the funniest material is rooted in truth. Comedians like to start with an awkward, bizarre, or unusual observation and then provide the flourish and exaggeration they need to make it humorous. The skill, therefore, comes not from being able to create witty jokes, but having the insightfulness to cherry-pick those witty jokes straight from the world. Comedy works do this all the time, from the opening traffic scene in Office Space to Louis C.K. recounting a time he got a little too high after a show. But this signature comedic approach is not limited to stand-up comics; it also can be found in the poetry of Thomas Lux.

Lux, the acclaimed poet and educator, passed away this February, and his loss deeply impacted the literary community. Over his life, he garnered respect from readers and fellow poets alike for his unique voice. As renowned poet Stanley Kunitz put it, “[He was] sui generis, his own kind of poet, unlike any of the fashions of his time” (Poets.org n.p.). Indeed, Lux’s diverse body of work, which includes everything from dark satire to lighthearted observations, stands apart from the poetic stereotype of high-class grandeur through its combination of familiarity and fantasy.

Lux began his career writing poetry in the 1970s, and his work heavily reflected the neo-surrealist movement of the time. Influenced by the likes of Bill Knott, John Berryman, and Pablo Neruda, Lux took on the disturbing, fragmented nature of the genre with apparent ease. In an excerpt of the poem “Five Men I Know” from Lux’s second collection, Memory’s Handgrenade, Lux writes:

The last one is being chased by a man

with a hammer. The man running

wears a body cast.

He has been wearing it for centuries.

The man with the hammer

wants to remove it.

The irony of Lux’s nonchalant tone amidst an almost nightmarish scene provides a clear indication of its comedic and satirical elements; the poem demonstrates Lux’s ability to combine humor with tragedy nearly seamlessly. As Lux told the Los Angeles Times, “I like to make the reader laugh–and then steal that laugh, right out of the throat. Because I think life is like that, tragedy right alongside humor” (qtd. by the Poetry Foundation, n.p.).

After his early work, Lux’s poetry began shifting to what he labeled as “imaginative realism,” applying his earlier techniques to more down-to-earth subjects. A large number of these subjects were rooted in his childhood. Lux was born in 1946, and he grew up as the son of the milkman on his family’s dairy farm in rural Northampton, Massachusetts. In “Cows,” the first of five poems he published in The New Yorker, Lux paints a vivid description of the cows from his youth, whom he unflatteringly described as “stupid / not cute;” Lux’s honesty here seems to ironically draw the poem away from his childhood and towards his more stoic and mature adult self. However, fitting with the theme, he expresses elements of nostalgia as he describes those days as “safe, tame, broken, and gone.” Similarly, in the poem “Cow Chases Boys,” he romanticizes his childhood, proclaiming, “Here / August lasted a million years.” Additionally, both poems include onomatopoeic descriptions (“trochee, trochee, trochee” and “boom,” respectively), which give them a more playful, childlike tone.

Listen to Lux read “Cow Chases Boys.”

Often times, Lux’s poetry reads like a work of stand-up comedy. His humor derives from a distinct type of introspection, providing the reader with unique angles of insight into things otherwise taken for granted. In many cases, you can almost hear a classic Jerry Seinfeld “What’s the deal with…?” in his poetry. While not usually laugh-out-loud funny, Lux’s poems, as is the case with “The Voice You Hear When You Read Silently” and “Refrigerator, 1957,” often force you to seriously think about otherwise unserious topics. In the latter, that unserious topic is maraschino cherries, which Lux describes as “fiery globes, / like strippers at a church social,” against the more mundane elements of the fridge. He cultivates a feeling of deep joy and passion for the cherries, concluding the poem by proclaiming that “you do not eat / that which rips your heart with joy.” Taken figuratively, this poem suggests a deeper truth about Lux: he both cares for and is well versed in picking out the little things in life. Other poems are indeed laugh-out-loud funny, but also express the same sentiment. In “I Love You Sweatheart,” Lux constructs a story out of a misspelled road sign love message. The list of questions (my favorite being “an idiot friend holding his legs?”) gives the poem its introspective tone, and the ultimate judgment of the sign as “blessed” expresses how Lux’s sense of humor is merged with his appreciation for love.

Lux has a very distinctive tone in his poems, almost always highly conversational and sound-driven, even when (and almost especially when) not literal in meaning. In doing so, Lux conveys an almost playful satisfaction in his poetry, where his musical, easy-to-understand nature make his poetry more accessible and enjoyable to readers. In “A Kiss,” he writes:

One wave falling forward meets another wave falling

forward. Well-water,

hand-hauled, mineral, cool, could be

a kiss, or pastures

fiery green after rain, before

the grazers. The kiss–like a shoal of fish whipped

one way, another way, like the fever dreams

of a million monkeys–the kiss

carry me–closer than your carotid artery–to you.

The first two lines set up a rhythmic quality, evoking the sense of a wave through alliteration and spacing. He continues, building a metaphor between nature and the kiss with wave-like sounds (“one way, another way”) and vivid, oxymoronic imagery (“fiery green”). Even with the romanticizing metaphor, though, Lux’s language is clear and concise, indicative of his realism.

The one exception to Lux’s colloquial tone in “A Kiss” is his reference to the “carotid artery.” Most of Lux’s poems are based largely in truth, but many also directly engage with (sometimes obscure) facts, as is the case in poems like “Henry Clay’s Mouth” and “Marine Snow at Mid-Depths and Down.” In the same way that Lux describes mundane things in a fantastical way for humorous purposes, he includes overly specific information to achieve that effect. In turn, his poetry indicates an underlying fascination with the specifics of how the world works, from the intricacies of science to bizarre historical tidbits, producing a pleasantly curious tone.

At his core, Lux, like any good poet, attempted to make sense out of the senseless world we live in. In works like “Plague Victims Catapulted Over Walls Into Besieged City” and “The People of the Other Village” (excerpted below), Lux discusses death and conflict in a darker, yet satirical, tone.

We do this, they do that.

They peel the larynx from one of our brothers’ throats.

We de-vein one of their sisters.

The quicksand pits they built were good.

The grotesque imagery evoked here serves as a harsh commentary on the human inclination towards violence. The use of hyperbole suggests that Lux is mainly critiquing peoples’ tendency to romanticize violence, which in turn leads to its perpetuity. Lux ends this poem with the powerful statement: “Ten thousand years, ten thousand / ten thousand brutal, beautiful years.” Taken at the surface level, the last line seemingly contradicts the rest of the poem by describing the 10,000 years of violence as “beautiful.” However, it serves two purposes: it establishes Lux’s almost intimate view of death and argues that imperfection, through passion, is what defines beauty.

In addition to writing poetry, Lux was also a well-respected educator and an inspiring leader in his craft. He was at faculty member at Sarah Lawrence College, Warren Wilson M.F.A. Program for Writers, and University of California, Irvine, and his alma mater, Emerson College. He also held the Bourne chair in poetry at Georgia Tech, where he ran the Poetry@Tech Program. That program, under the guidance of Lux, is now “one of the premier showcases of poetry in the Southeast,” according to the Poetry@Tech website, featuring acclaimed poets from all over the world. Lux’s love of poetry was perhaps best expressed in this project, as it demonstrates his willingness to spread his love and understanding of poetry to younger generations of less experienced people. “He had a great feeling for the common man, the underdog, and the person who was trying to do something,” said Professor John Skoyles, a colleague of Lux at Georgia Tech (Emerson College n.p.). Both in his writing and his actions, Lux expressed this love of the less looked-upon.

Ultimately, Lux’s work gets at something deeper. Through his comedic realism, attention to and love of detail, and “common man” persona, Lux called for the embrace of individuality and expressed a benign view of humanity. In an age of unprecedented diversity, but also polarization, these themes are as relevant as ever. His poetry serves as more than just entertainment or a basis for literary discussion; it both demonstrates and to some extent irradiates the qualities of a good human being.

While many are saddened by Lux’s passing, it’s important to realize how he, through his combination of humor and darkness, light and despair, seemed to come to terms with death. It’s said that he once commented, “I have died so little today, friend, forgive me.” Who else but a true comedian–a true poet–could speak those words?

Works Cited

Christiansen, Paul. “Blotto in the Lifeboat.” FIU Digital Commons. Florida International University, 2 Mar. 2015. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2909&context=etd.

Clossey, Erin. “Thomas Lux ’70 a ‘Robust And Tender’ Poet, Teacher.” Emerson College, 22 Feb. 2017. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. http://www.emerson.edu/news-events/emerson-college-today/thomas-lux-70-robust-tender-poet-teacher#.WPAlEVMrLVo.

Lux, Thomas. “Cow Chases Boys.” The New Yorker. The New Yorker Archives, 16 Mar. 2015. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/03/23/cow-chases-boys.

—. “Cows.” The New Yorker. The New Yorker Archives, 4 Apr. 1993. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1993/04/05/cows-2.

–. “Five Men I Know.” Memory’s Handgrenade. Pym-Randall, 1972. Print.

—. “I Love You Sweatheart.” Poem Hunter. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/i-love-you-sweatheart/.

—. “A Kiss.” Poem Hunter. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/a-kiss-3/.

—. “The People of the Other Village.” Poetry Foundation. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/48485.

—. “Refrigerator, 1957.”The New Yorker. The New Yorker Archives, 28 Jul. 1997. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/07/28/refrigerator-1957.

“Poetry@Tech.” Georgia Institute of Technology Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts. Georgia Institute of Technology, n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. https://poetry.gatech.edu/.

“Sunbeams.” The Sun. The Sun Magazine, Feb. 2005. Web 13 Apr. 2017. http://thesunmagazine.org/issues/350/sunbeams.

“Thomas Lux.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/thomas-lux#.

“Thomas Lux.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets, 15 Mar. 2017. Web. 13 Apr. 2017. https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/thomas-lux.