This article is a collaboration, featuring Jeff Howard (who also compiled and edited this article), Dongho Cha, Hyeryung Hwang, Alok Amatya, and Ben Bergholtz. For more information on World Englishes at Georgia Tech, visit the World Englishes Committee website, World Englishes: Linguistic Variety, Global Society. Howard’s introductory Prezi on World Englishes is a meaningful resource for instructors and students interested to know more.

Introduction: World Englishes and Multimodality

Over the past few decades, international students on college campuses across the US have fostered increased diversity and multiculturalization in composition classrooms. As instructors of multimodal composition, we believe that for international college students who are English language learners (ELL) multimodality allows students to access and engage more thoroughly with course materials and projects across existing cultural and literacy barriers, even promoting a sense of intercultural companionship between students. Specifically, multimodal texts and assignments provide an effective means of bridging the divides that often marginalize international students within mainstream composition classrooms.

Multimodal communication consists of the interweaving of multiple systems of meaning, including written, oral, and visual modalities. Image taken from The Visual and Multimodal Research Forum.

During the 2018-19 academic year, the members of the Georgia Tech Writing and Communication Program’s World Englishes Committee collaborated to produce a series of short pieces responding to the common concerns of many ELL students in multimodal composition courses. Given the multimodal framework developed by the Writing and Communication Program, Georgia Tech instructors are well-positioned to prepare their students to communicate in an “increasingly global world” and take advantage of the many literacies our diverse student population brings into our courses. The purpose of the pieces compiled in this article is thus to provide instructors with advice they can look to as they strive to meet the specific communication and cultural needs of the international and multilingual student populations who enroll in multimodal composition courses like Georgia Tech’s English 1101/1102 seminars. We acknowledge that the extensive and complex challenges faced by ELL students will require much more collaboration and knowledge than we can provide here. Nonetheless, these short articles provide insight into the struggles of some of our own students, as well as ideas for offering them additional support where needed.

—Dongho Cha, Independent Scholar and Former Brittain Fellow, and Jeff Howard, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow and Assistant Co-director of the Naugle Communication Center

Collaborating Across Cultures

Collaborative projects allow students an opportunity to learn specific techniques for communicating and solving problems across cultures. In this process, ELL students integrate different cultural influences and intellectual perspectives into their coursework. Studies show that diversity in teams can lead to greater creativity (Bassett-Jones 171). Diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds not only lay the foundations for complex discussions that promote cross-cultural understanding, but they can also improve the overall quality of a project.

Disadvantaged by their language status, ELL students can find it challenging to collaborate with native-speaking peers. Comparing themselves to their classmates, ELL students can be concerned about possible misunderstandings, subsequently leading them to follow the other, more dominant voices in their group projects, rather than placing their own views front and center.

To help ELL students overcome the fear of communication, instructors should encourage ELL students to embrace the strengths of their language backgrounds through written feedback and oral conferencing. An instructor’s recognition may allow students to identify themselves less as non-native speakers of English and more as multilingual speakers, helping them to embrace miscommunication as part of the process for multilingual exchanges. When they are less afraid of making errors, students can come to understand the process of collaborating with native speaking peers as an empowering opportunity to sharpen their language and social skills, to see value in their ideas, and to improve their group work. Further, equal participation among group members is essential to building a successful team dynamic. By fostering these kinds of attitudes and perspectives in their classrooms, instructors can facilitate the student development as they learn to harness the power and opportunities that diversity can offer in group situations.

—Hyeryung Hwang, Assistant Professor of English at McNeese State University and Former Brittain Fellow

The Multimodal Diagnostic Video

The Common First Week Video is a short, multimodal diagnostic assignment during the first week of English 1101/1102 that provides a snapshot of the level of students’ communication skills at the beginning of the semester. Due for submission in the second week of classes and worth 1-5% of the total course grade, the assignment exemplifies the kind of work instructors expect students to put into the course throughout the semester.

Student’s Multimodal Diagnostic Video. Image via YouTube, screen capture (2019).

The Diagnostic Video aims to habituate students to the composition process, which involves conceiving the work of creating an artifact in small and connected tasks. Rather than trying to create the finished artifact in one attempt, students should work on tasks like creating an outline, drafting their script, practicing and recording their delivery multiple times, and editing the recorded video. This approach allows students to compose a better artifact, although it also requires them to start working on the assignment with plenty of time to spare.

Attending to the composition process of the diagnostic video allows students to build on their strengths while working on their weaknesses. For instance, many ELL students may struggle with pronunciation due to the phonological interference from their native languages. Part of the problem has to do with their level of linguistic knowledge. ELL students might have what linguistic refer to as errors in their language because they simply are not aware of certain linguistic rules or vocabulary. They might also experience mistakes (another linguistic term), which refer to lapses in communicative performance or application despite knowing the correct linguistic rule for the situation. These mistakes can result from multiple factors, including lack of attention and stress.

Instructors can therefore encourage ELL students to rehearse the delivery of their script by making several recordings until they get the desired result. Breaking the script into smaller chunks so they have less to memorize can be a good strategy as well, even if it means that students must record more shots to edit together on the back end. Ultimately, the more class time instructors devote to providing strategies for communication, time management, and coping with anxiety or stress, the better prepared ELL students will be to produce a quality artifact.

—Alok Amatya, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow and Professional Consultant at the Naugle Communication Center

Audience, Assignment Descriptions, and “Power Distance”

When instructors create assignment descriptions, they take into account many variables: context, goals, definitions, instructions, outcomes, assessment, diction, etc. However, like other communicators, instructors may not always consider who they are trying to communicate with when crafting their document. Perhaps they want lose sight of certain variables as they attempt to emphasize others. Perhaps they are rushed or stressed or exhausted. Such considerations are important parts of the process of assignment instructions, but they may have unforeseen results.

For example, when instructors talk about material from their field, it is easy for them to forget that they are attempting to communicate to outsiders—intelligent ones, yes, but outsiders regardless—who are unfamiliar with the vocabulary, methodologies, theories, practices, names, or other elements required to comprehend the material. For students who are already learning a new language, introducing new discipline-specific terms can form a barrier to understanding. Simple, straight-forward English is therefore essential to promoting complete understanding.

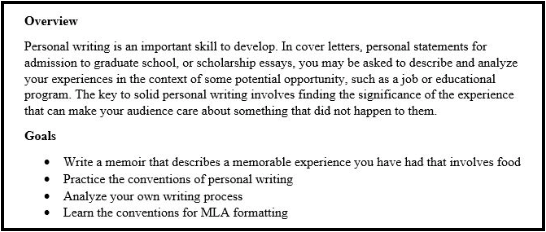

Instructors need to create specific and thorough assignment descriptions without sacrificing clarity and simplicity. Partial assignment description, English 1101, Jeff Howard (2019).

Thoroughness and specificity are positive attributes, but they can also work against instructors if the result is a bulky, complicated document that offers too much information. If an assignment description contains more information than ELL students can process at a given time, they may not absorb all the instructions or give up before finishing. Instructors should explicitly encourage their students to meet with them after class or during their office hours should they require additional clarification.

Still, in some countries, regions, or cultures where “power distance” is significant (countries in Asia and the Middle East, for example), a student asking the instructor such questions may be interpreted as a challenge to the instructor’s authority. The term “power distance” comes from Geert Hofstede’s theory of cultural dimensions, and it refers to the degree to which “less powerful members of institutions and organizations accept that power is distributed unequally” (Sweetman). The higher the power distance index of a culture, the less likely it is, according to the theory, that individuals will perceive themselves as equals with a person in authority. As a result of perceived “power distance,” some ELL students who need clarification will not ask for it.

In our university context, “power distance” is rarely an issue, as many ELL students are not shy about staying after class to have a concern resolved, but it is something to be aware of. Instructors need to invite such exchanges early and often in the semester because they can lead to collaborative knowledge-making and lead instructors (1) to re-examine their own rhetorical decisions and (2) to produce clearer assignment descriptions that support the progress of their students.

—Jeff Howard, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow and Assistant Co-director of the Naugle Communication Center

Integrating Quotations from Sources

Not all academic communities value the practice of integrating secondary research with the same level of gravity as members of the western academic tradition. We warn our students again and again that borrowing the words or original ideas of another without recognizing their contribution is a serious breach of academic integrity. Many ELL students come from academic cultures or background with different perspectives on the practice of research writing. It is not simply a matter of teaching these students how to integrate and attribute research, but also why the western academic tradition cares so deeply about attribution and citation. Instructors cannot ignore the need for teaching students these fundamental aspects of research writing, especially since the stakes are so high when students fail to adhere to the standards for academic integrity.

Direct quotations from a text can be an important aspect of a written assignment or a multimodal artifact. The proper use of direct quotations enables a writer to engage deeply with the ideas of another text or person, thus adding depth, specificity, and credibility to an argument. In several instances, quotations from a reliable source serve as textual evidence that supports an argument. However, students need to understand that placing borrowed words within quotation marks is only an elementary step of the composition process. To integrate a direct quotation smoothly requires practice and application.

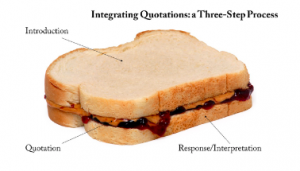

A well-integrated quotation “sandwiches” a quotation between an introduction, which supplies important contextual information, and a response or interpretation of the quotation that elaborates on its meaning and relevance to the argument.

It may be helpful for students to think of integrating quotations as a three-step process. The first and the third steps involve writing in your own words about the ideas addressed in the quotation, while the second step involves selection and placement. To use a food metaphor, a properly integrated quotation is like a sandwich, i.e., the writer’s words being the bread that holds together the filling. Remember that “sandwiching” a quotation helps a writer weave another person’s ideas into the fabric of your artifact, centering the audience’s attention on the writer’s interpretation of the quoted words, in the same way the pieces of bread elevate the flavors of the tomato, lettuce, and chicken in a sandwich.

However an instructor understands these components of effective and ethical research writing, the students need to hear about it. Do not expect someone else to let them know about it, and never assume they already know everything there is to know about it. Chances are, your class may consist of ELL students who need additional support in this area, particularly if they come from a culture with different ideas about knowledge and knowledge-sharing in academic situations. By understanding that members of some societies or cultures have different perspectives on academic practices, instructors will be in a better position not to police their students, but to steer them away from pitfalls or habits that stem from a lack of knowledge regarding western academic culture and its conventions and ethical standards.

—Alok Amatya, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow and Professional Consultant at the Naugle Communication Center

Fair Representation of Sources

Due to linguistic barriers, ELL students can find themselves struggling to fairly represent source material, such as scholarly books or articles, in research projects. “Fair representation” signifies more than simply providing adequate citation and attribution, although these are important steps to observe. Citation is the first step of ethical or “fair” utilization of secondary source material in research writing. Providing enough context for an accurate summary or paraphrase of source material can help students to create more readable documents and preempt logical breakdowns or fallacious reasoning, often in the form of “straw man” arguments.

In writing and research, students may create straw man arguments by altering another author’s meaning or arguments in such a way that they become easier to disprove presenting a version of the argument that was never put forward. Some may construct straw men intentionally because they want to increase the appeal of their own argument. Some students do so unintentionally, though.

Not all misrepresentations are so unethical, yet straw man fallacies may occur just the same, even accidentally. For students learning English, straw men can happen because of simple misunderstandings in reading, writing, speaking, or listening. Translation does not always render nuance clearly into other languages, so even well-meaning students may miss important aspects of a source and transform it into a reductive or inaccurate version of the original.

To steer clear of such fallacies, instructors should encourage ELL students to talk to area specialists or content area tutors on campus, or visit writing or communication centers, such as Georgia Tech’s own Communication Center. If the misrepresentation happened because of issues in non-productive communicative performance (listening or reading), a content expert, such as a professor or TA in that or a related discipline, can be a useful resource. If the misrepresentation happened because of issues of productive communicative performance (writing or speaking), a fresh set of trained eyes can often clear it up. Even asking a friend to look over a piece of research writing can be one way for ELL students to weed out summaries that misconstrue or misrepresent concepts or ideas in their writing.

—Jeff Howard, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow and Assistant Co-director of the Naugle Communication Center

Approaching Oral Presentations with English Language Learners

Oral presentations are challenging for most students. Glossophobia, or the fear of public speaking, is one reason. Dr. Glenn Croston in Psychology Today writes, “Surveys about our fears commonly show fear of public speaking at the top of the list. Our fear of standing up in front of a group and talking is so great that we fear it more than death” (“The Thing We Fear More Than Death”). For ELL students, however, the linguistic and cultural challenges of delivering an oral presentation can compound the anxiety-inducing constraints of social phobia, even for those ELL students who are quite proficient in informal classroom communication. ELL students may struggle with many factors associated with more formal classroom presentations, including a lack of familiarity with the conventions of academic English, a lack of experience delivering presentations in classroom settings, and a lack of practice employing multimodal technology during oral presentations.

This is the case not simply because ELL students are presenting in a non-native language, but also because what constitutes “successful” communication practices are culturally specific rather than universal in nature. In American classrooms, for example, students giving oral presentations are often taught to smile, appear energetic, ask questions of their audience, and use electronic and visual aids such as Prezi or Google Slides. When American students arrive in college, then, they may not realize that their ELL peers’ have often been taught entirely different sets of presentation norms, and, hence, they may have entirely different conceptions of what constitutes a “successful” oral presentation.

This cultural divergence can create challenges in both individual and group presentations. Individually, ELL students may struggle to adapt and implement the norms of US classroom presentations after years of adopting different practices. In groups, ELL students and native speakers may struggle to recognize and reconcile why they have different understandings of what makes a successful oral presentation. To help students grapple with these challenges, instructors may consider the following two points:

- First, make sure that students understand what the expectations for oral presentations are in this rhetorical situation. Expectations are culturally and even classroom specific. Reading assignment sheets and rubrics carefully, as well as asking the instructor for clarification when questions arise, are effective ways to help students to discern new and potentially confusing academic standards.

- Second, once the expectations are made clear, we advise instructors to encourage ELL students and native speakers preparing oral presentations to practice on several occasions. Practice, especially over an extended timeframe, is always a wise choice. It is especially useful in this context because it provides students the opportunity to see whether or not their oral presentations are meeting the expectations of the particular rhetorical situation and to adjust accordingly, before the actual presentation.

When evaluating the presentations of ELL students, then, instructors and students may find it fruitful to focus less on correctness (e.g., “you mispronounced this word”) and more on the overall content and coherence of the presentation (e.g., the quality and clarity of the thesis, the use of supporting evidence, and the persuasiveness of the argument). By focusing first on content and coherence, native speakers can give a fair appraisal of the overall quality of their ELL peers’ oral presentations while still giving feedback on their acquisition of the culturally specific aspects of oral communication, such as voice, appropriate and effective visuals, and audience engagement.

—Ben Bergholtz, Assistant Professor of 20th and 21st century American Literature at Louisiana Tech University and Former Brittain Fellow

Global Graphic Genres for ELL Students

Due to the increasing popularity of comic books and graphic novels, as well as the support provided by critical works by comic theorists like Scott McCloud and Will Eisner, graphic genres are becoming more and more popular in university and K-12 classrooms.

Global graphic genres present complicated themes and challenges—involving combinations of historical representations and social issues—to readers through text and illustrations. Graphic novels commonly adopted as textbooks for college students include Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1980), a chronicle of the author’s father’s experience during the Holocaust, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), a memoir of the author’s adolescence amid the Iranian revolution. For ELL students in communication courses, graphic genres also have been found to be particularly successful in developing vocabulary and grammar.

Researchers have also found that visual support has a positive effect for ELL students on reading comprehension and critical thinking (see Marcus, Cooper, & Sweller; Paivio; Sadoski). Illustrations provide contextual support and clues to the meaning of the written narrative; and graphic genres help students to bridge the gap between intellectual capacity and linguistic ability.

Reading global graphic genres may also allow ELL students to connect literature to their own experiences. If students are familiar with the worlds displayed in graphic work, they can utilize their knowledge to educate their peers who might not be familiar with the work’s cultural context. Thus, global graphic texts may encourage ELL students to contribute to class discussions and help to grow their self-confidence in English-language classrooms. While some instructors new to or unfamiliar with the field of graphic genres may feel reluctant to adopt or incorporate such works into their syllabi, there are plenty of resources on the subject of graphic novels and literacy to help them venture into the field, including the NCTE’s statement on Using Comics and Graphic Novels in the Classroom, Sarah Knutson’s web article “How Graphic Novels Help Students Develop Critical Skills,” and NPR’s list of influential graphic novels in “Let’s Get Graphic: 100 Favorite Comics And Graphic Novels.”

—Hyeryung Hwang, Assistant Professor of English at McNeese State University and Former Brittain Fellow

Conclusion

If you are an instructor who wants to learn more about English language learning students and build your professional repository of knowledge and resources, we invite you to visit our web site, World Englishes: Linguistic Variety, Global Society. The World Englishes Committee strives to support instructors contributing to the education of English language learners at Georgia Tech, as well as promote intercultural education, engagement, and exchange. We believe that well-informed composition instructors are essential to improving the educational experience of multilingual students from diverse backgrounds.

Works Cited

Bassett-Jones, Nigel. “The Paradox of Diversity Management, Creativity and Innovation.” Creativity and Innovation Management, vol. 14, no. 2, 2005, 169–75. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8691.00337.x.

Croston, Glenn. “The Thing We Fear More Than Death.” Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, LLC, Nov. 29, 2012. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-real-story-risk/201211/the-thing-we-fear-more-death.

Marcus, Nadine, Cooper, Martin., and Sweller, John. “Understanding Instructions.” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 88, no. 1, 1996, 49-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.88.1.49.

Paivio, Allan. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. Vol. 9. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Sadoski, Mark. “Resolving the effects of concreteness on interest, comprehension, and learning important ideas from text.” Educational Psychology Review, vol. 13, no. 3, 2001, 263–81.

Sweetman, Kate. “In Asia, Power Gets in the Way.” Harvard Business Review, HBR, 10 Apr. 2012, https://hbr.org/2012/04/in-asia-power-gets-in-the-way.