Banner image for The Censorship Files, courtesy of the author. https://thecensorshipfiles.wordpress.com/

When teaching the art of research writing, I aim to help my students learn the tools of the communication trade through assignments that challenge them to see the world with more conscientious eyes. I strive to help my students recognize not only that the forms of their words matter but that their ideas actively contribute to the world in which we live.

It was out of this desire that I organized my recent composition and media studies course around a topic of great importance to our past and our present: censorship. Our course title, “The Censorship Files: A Study of Texts, Images, and Information,” emphasized the broad nature of this theme and the diversity of media that the students would investigate.

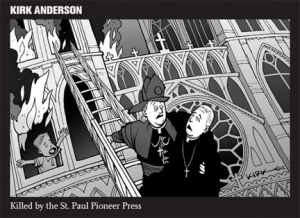

A “killed cartoon” by Kirk Anderson. http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/article/Killed-cartoons-Censorship-is-a-threat-not-only-2611257.php#photo-2097541

During the semester, my students produced a range of artifacts. They analyzed the visual rhetoric of “killed,” or censored, political cartoons. They composed personal reflective essays in which they produced their own original metaphors for how censorship functions historically and today. These essays were titled and modeled after Salman Rushdie’s influential article, “On Censorship,” which was adapted from a longer speech and published in The New Yorker in 2012.

The bulk of the semester, however, was devoted to an experimental digital assignment that asked the students to take an active and public part in illuminating the role that censorship has played in the past and present. This project required them to design The Censorship Files, a website and digital journal devoted to their interactive, multimodal editorials on censored artifacts and events. Collaboratively composed, their essays tackled topics ranging from the censorship of J.D. Salinger’s controversial classic, The Catcher in the Rye, to South African artist Brett Bailey’s politically-charged human art installation, Exhibit B, to Costa-Gavras’s 1982 film, Missing, which depicts the true-life disappearance of an American journalist in Chile during Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup d’état. Not all editorials, however, covered creative products. One group examined the censorship of scientific research on mutations of the H5N1 Virus while another studied Nelson Mandela’s 1962 arrest.

With these editorials, I tasked the students with becoming investigative reporters, using their writing as vehicles, not to persuade their audience that a censored artifact or event was (un)justified, but to elucidate the complex histories through which the censorship occurred. Adopting a journalistic style, they delved into the messy circumstances themselves, presenting the facts as objectively as possible through a variety of images, videos, infographics, maps, legal documents, peer-reviewed secondary sources, and more.

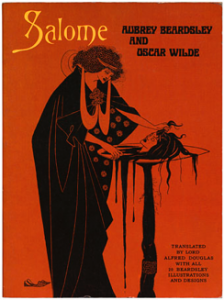

Oscar Wilde’s 1894 play, Salome, was censored in England. http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2008/01/20/beardsleys-salome/

These editorials were complemented by personal interviews that the students conducted with professors, public figures, and other relevant experts. The students published their interview transcripts on our website and then used them as primary sources to bolster their editorials. One group, for instance, consulted University of Georgia English professor Adam Parks on the censorship of Oscar Wilde’s “scandalous” play Salome. Another group discussed with art critic and translator Lee Ambrozy the censorship of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s personal blog due to his unabashedly scathing indictment of the Chinese government. O. Henry award winner, David Bradley, offered another team a memorable commentary on the censorship of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in American secondary schools. In the interview, Bradley evinces the novel’s historical significance and articulates its radical pertinence to our political present. All of these interviews conveyed the dynamic social, cultural, and political issues surrounding the various artifacts and events themselves. But even more, these interviews allowed the students to see their work as involved in—as shaping—broader discourse communities. By directing their interviews, the students recognized their individual power to produce live-action information useful to their own research and to the development of public dialogue around their chosen subjects. Thus, they came to see the research process as a kind of living organism that does not necessarily begin and end in the university library’s databases. They also saw themselves as reporters, out in the field, participating in the variable and courageous knowledge-generating process in which journalists routinely engage.

As The Censorship Files came together, my students were able to see their own work in conversation not only with the ideas of their interviewees but also with their peers. With their own rhetorical awareness more acutely sharpened, they recognized that, although their groups’ topics were diverse, when read together, the editorials illuminated a host of common trends and stakes in which censorship is often entangled.

Once the website was complete, the students promoted their publications on our class twitter account. “How a single film caused a national uproar: France’s response to The Battle of Algiers (1966),” wrote one group. From another: “Farewell My Concubine: Acclaimed in Cannes, Banned in China.” With these snappy teasers, the students promoted their creations through a social media platform that is now essential for public communication.

The iconic “Tank Man” photograph from the Tiananmen Square Massacre. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tianasquare.jpg

Already, I have observed that The Censorship Files is making a public impact, with the website garnering daily hits from around the world. On March 10, 2017, the digital journal received 30 individual visitors, tallying 113 separate page views, from 6 different countries (ordered here from the largest to the smallest number of visitors): the United States, Japan, Canada, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom. During the preceding month, however, visitors from India, Singapore, Hong Kong, Bulgaria, Ireland, Mexico, Russia, Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, New Zealand, Malaysia, Austria, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, France, Finland, Turkey, Italy, Indonesia, Brazil, and simply too many more to name have registered frequent numbers of visitors. Two of the website’s most popular editorials examine the Tiananmen Square Massacre and The Communist Manifesto, with the former trending at 88 views in the past 30 days and the latter trending at 94 views. The editorial for which I have received the most unsolicited and affirming feedback is one group’s sophisticated study of Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 Soviet film, Battleship Potemkin. These statistics and commendations speak loudly of the potential for undergraduate students—and in my case, first-year students—to produce engaging research projects of interest to the broader American public and other audiences from around the globe. Indeed, the global nature of the students’ editorial topics themselves affirm that the issue of censorship is one waged at home and abroad, across cultural and political spectrums, superseding boundaries of difference.

Altogether, this assignment strengthened my students’ research and analytical skills while increasing their understanding of censorship’s historical roles. Yet the project also prompted the students to contend with the relationship between media, design, and meaning as the teams employed digital tools to help them shape, convey, and promote their knowledge in a visually-appealing, organized, and public-facing electronic format. These various skills together are foundational in professional industries and the academy, where knowledge is rarely exchanged through a single mode of communication. For journalists, businesspeople, and engineers alike, knowledge is always circulated through a variety of written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal modes of communication.

The Nuts and Bolts

Envisioning such a digital writing project is grand in and of itself, but implementing the assignment is a much taller order. When designing the prompt, I found that I needed to scaffold the assignment into parse-able, palatable pieces. My goal was to make The Censorship Files an approachable, manageable project, one that would excite my students while equipping them with essential research skills. With these aims in mind, I divided the assignment into a series of steps (detailed below) that took approximately two months to complete.

First, I assigned the students to teams of two or three. These teams composed a short topic proposal that shared two possible artifacts or events that they might research. This proposal gave me the opportunity to help students narrow their thoughts when, for instance, they proposed discussing an impossibly-large topic such as China’s “Great Firewall.” Through my feedback, the group revised the proposal to study the more manageable topic of Google’s censorship in China. These proposals were then expanded into a memorandum in which the students presented a rationale for all of the media and sources they planned to incorporate into their essays. These memorandums later served as the basis for each group’s in-class pitch presentation. Speaking directly to their peers, they outlined their topic, sources, production plans, and potential challenges and solutions. These presentations concluded with a few minutes devoted to inquiries, recommendations, and affirmations from peers.

The students next sought to arrange personal interviews. To prepare, I devoted class periods to discussing email and interview etiquette, the composition of effective interview questions, and strategies for identifying academic and public figures currently publishing on or advocating on behalf of their topics. Using the Irish government’s banning of Kate O’Brien’s 1941 novel, The Land of Spices, as an example, I demonstrated the different kinds of experts I could potentially contact, including an O’Brien literary scholar, a historian of Irish censorship, or an authority on the connection between censorship and sexuality. Each of these categories of experts could provide a different set of insights pertinent to an editorial on O’Brien’s novel. I also pointed the students to national advocacy groups, such as the Index on Censorship, the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), and the National Council of Teachers of English’s (NCTE) Intellectual Freedom Center.

Following these preparatory lectures, the students contacted at least two relevant specialists with requests for email interviews. They CCed my university email address to these messages. In their emails, the students made it clear that their goal was twofold: 1) to use the interview as a primary source in their editorial and 2) to publish the full interview transcript on our website, which they hyperlinked within the message. Groups that were unable to secure an interview were not penalized. With that said, most groups were able to locate an interviewee. On this point, I found that—beyond using personalized, succinct, and courteous email messages—there was no discernible formula for guaranteeing an interview.

Before conducting their official interviews, I vetted each group’s set of questions. After completing their interviews, the students edited the transcripts for typographical errors and formatted them for publication. At this time, the students asked their interviewees if they would like to include a personal photograph alongside their published interview. Most happily obliged. Additionally, many interviewees contacted me personally to convey their enthusiasm about participating in the project, and several shared their published interview transcripts on their personal twitter and Facebook accounts, promoting The Censorship Files while also amplifying their own public profiles.

“The Censorship Files” on Twitter. https://twitter.com/censorshipfiles

The final stages of the project included an in-class peer-review session followed by the publication of the editorials themselves. Because of the public nature of the assignment, I allowed each group to revise its editorial for a higher grade based on my detailed feedback. Once revised, the teams emailed me 140 character “teasers” that I tweeted on our class Twitter account.

Two additional variables were significant to the success of this assignment.

First, it is worth mentioning that I selected WordPress as our project’s digital platform because it is free and simple to use. It also allowed me to control the level of accessibility each student had to our website. While I retained all rights as an “administrator,” I chose to add my students as “editors.” Another bonus to using WordPress is that when students troubleshoot technical issues, there are numerous resources available online—sponsored by both the service itself and its users—that they can locate independently. This external support proved especially important when I realized that most of my students were unfamiliar with web design and development. Nonetheless, I still spent short segments of class periods showing my students how to utilize different features of the website. As their projects progressed, I found that we rarely discussed technical issues. I remember only one occasion when some students mentioned having difficulties with embedding videos within their editorials. Their peers quickly chimed in and addressed these concerns before I could even speak.

Second, before beginning the project, I required each student to fill out an “Agreement Form,” promising that he or she would not abuse our website or tamper with peers’ editorials. Each student also agreed to publish under his or her legal name or a pseudonym of choice. While most students chose to use their legal names, a few opted to publish under pseudonyms. Altogether, due to the public nature of the assignment, this form was essential. It protected the website and the students themselves.

When finalizing the website, I found that even though the students’ editorials were not all of a professional grade—although some, I would argue, are—they are each evidence of remarkable journeys. Over the course of the semester, I witnessed my students becoming stronger, more confident researchers, writers, and collaborators. They also became deeply invested in the issue of censorship itself, its advantages and pitfalls. While my goal for the course was never to prove that censorship is inherently “good” or “bad,” I did seek to show them that issues of national and international importance—issues like censorship—are not easily reducible to single histories and assessments. Rather, they are multifaceted and manifest uniquely in different places and times.

I also saw our course as offering the students another practical boon: a publication. Thus, I encouraged my students to add the citations of their editorials to their resumes and curriculum vitae. We live in a time when the job market is especially competitive, and no matter students’ majors, evidence of strong research and communication skills can set them apart from other candidates. A digital publication may, indeed, serve as memorable fodder in a future job interview. I see The Censorship Files, then, as not just a vehicle for public historical analysis or a means for acquiring academic research skills but also as a potential edge in professional marketability. The range of these instructional advantages together made facilitating the creation of this digital project both pedagogically gratifying and personally inspiring.