This mural was painted by Tristan “TK” Irving during summer 2020 on in Old Town, Portland. “Black Lives Matter memorial mural” by Sarahmirk is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

In response to the protests for racial justice during the summer of 2020, we here at TECHStyle discussed steps we could take to promote antiracism and antiracist pedagogy in higher education. As we noted in our call for submissions from August, “Black people have experienced systemic racism for as long as America has been an idea. Higher education has—despite efforts by some scholars—perpetuated the discrimination and dehumanization of Black people.” These six reflections on antiracist pedagogy, then, serve as examples of the work Brittain Fellows are undertaking to make higher education a more equitable and inclusive space. We share their insights here, hoping that they can inspire others.

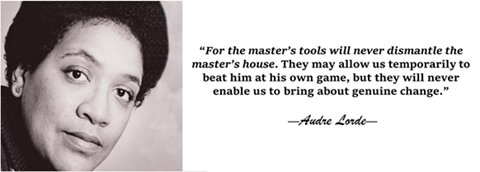

“Abandon the ‘Master’s Tools’: A Mandate for Antiracist Pedagogy” by Julia Tigner

At its core, antiracist ped agogy seeks to abandon reliance on the “master’s tools” and prioritizes instead diverse social locations and knowledge production that underscore historically marginalized perspectives and viewpoints (Lorde 112; emphasis in the original). However, the “master’s tools” remain at the heart of the academy’s basic language (Lorde 112; emphasis in the original). As Audre Lorde asserts in “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” “genuine change” cannot exist if the academy continues to use the master’s language to “dismantle” his ideology (112).

agogy seeks to abandon reliance on the “master’s tools” and prioritizes instead diverse social locations and knowledge production that underscore historically marginalized perspectives and viewpoints (Lorde 112; emphasis in the original). However, the “master’s tools” remain at the heart of the academy’s basic language (Lorde 112; emphasis in the original). As Audre Lorde asserts in “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” “genuine change” cannot exist if the academy continues to use the master’s language to “dismantle” his ideology (112).

As we ponder this more inclusive approach to teaching, it is first imperative to ask: Can there be antiracist pedagogy if the academy does not divest itself of its own racial privilege?

Antiracist pedagogy acknowledges Americans’ complicity in the perpetuation of racism, but I am not convinced that the academy recognizes its own complicity in perpetuating the discrimination and dehumanization of Black people.

Sentiments such as “I didn’t know,” “I agree Black lives do matter, but…,” and “What can I do?” reveal the pervasive privilege present in the academy that turns a blind eye to the daily injustices facing people of color, particularly Black people, and that constantly places the onus on Black bodies to inform, teach, and labor—a reminder that “opting in” to racial awareness is a requirement for some, and a choice for others, when it should be foundational to all.

The #BlackLivesMatter movement has finally resonated with larger society. In response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless others, many academics have felt compelled to incorporate antiracist practices in their pedagogy. Many others have always done so. Some may argue that I should be pleased; this trend signifies progress, right? Yet I cannot help but question the sincerity. When the dust settles, will these “newly awakened” academics still care? Or will these conversations be a distant memory?

The academy must do more than pay lip service to the #BlackLivesMatter movement and be held to account for the promises made this summer about thoughtfully integrating antiracist pedagogy. We must develop genuine skills and take shared responsibility for making antiracist methodologies foundational to our pedagogies, regardless of teaching topic. We must stop avoiding discussions about race and lean into our discomforts. We must rid ourselves of excuses. Yes, race is a complex conversation, but it informs everyone’s realities. Thus, we must equip students and ourselves with the antiracist language skills and discussion skills to address uncomfortable topics.

As academics, we all have a responsibility to our communities to help create this broader institutional change. If we opt out and allow our students to opt out, this work will wither on the vine. But if we learn how to prioritize, share, and lean into our discomforts around conversations of race, a slow but foundational change may yet be possible.

“Race and the Embodied Poem: Using Slam Poetry to Confront the Limits of Textual Analysis” by Lizzy LeRud

When the #BlackLivesMatter movement emerged in 2013—during a summer stained by the acquittal of George Zimmerman after he killed Trayvon Martin—I was still a new teacher, just entering my second academic year as a solo instructor of first-year writing. The program I taught in was highly structured, intended to support new teachers like me. While there wasn’t much room to make changes to my class, I knew I needed to do something to account for these seismic shifts in our cultural conversation about racism. I retooled my syllabus in the ways that I could, swapping out a standard set of (rather white) readings for works by Black writers. Eventually, as I took on new teaching assignments, these classes evolved into other English classes that focused topically on race and racism, using readings like Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates and Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine. But as the movement grew this summer—as video after video of Black people being killed by the police went viral—I decided that it wasn’t enough to diversify my syllabus and read about racism with my students. I needed to examine my pedagogy itself for the ways it controlled how students approach the artistic expressions of writers of color.

I turned this time to another set of viral videos proliferating on sharing platforms, those three-minute poems we think of as “slam poems,” increasingly produced by young LGBTQIA people of color, including many poets and rappers still in college. Despite how the popular media disparages these performances as mere melodrama punctuated by appreciative finger snapping (witness this example from 22 Jump Street and this one from A Goofy Movie), works by these artists have long been popular among my students. I couldn’t help but encourage their admiration. After all, the voices in the videos are joyful, confident, unapologetic, inventive, and sharply incisive: consider Porsha Olayiwola’s scathing critique of capitalism, Denise Frohman’s celebration of feminine self-assertion, or Hieu Minh Nguyen’s “Notes on Staying,” which explores the emotional landscape of chronic depression.

But when it comes to studying these performed poems, the tools of traditional textual criticism fail. The analytical toolkit I usually give poetry students is built for the written page, suited for understanding stanza and line, syllable patterns, and figures of language, but unable to account for volume, speed, intonation, and timbre. Focusing on these poems as texts meant leaving out so much that’s integral to the voices themselves—not to mention the gestures, eye contact, and skin tones of these writers, integral elements to the performances of these poets. In other words, textual criticism could account for Olayiwola’s argument, but it tended to obscure her Blackness.

Learning to study these works of art forced me and my students to examine how ideologies of cultural dominance infiltrate conversations that don’t center obviously on race, like the ways our Western classrooms have long taught us to analyze poems first as texts, not embodied speech. This time, to urge our focus toward the specific voices of these writers of color, I’ve begun teaching analysis using Gentle and Drift, digital tools built on predictive speech software, which help us account for the unique texture and style of a poet’s vocal performance. It’s only a start, as taking the #BlackLivesMatter movement seriously means constantly assessing our classrooms for injustice. There’s much more work to do.

“#BLM and Anti-Racist Digital Humanities Pedagogy” by Katie Schaag

Computational algorithms are inextricable from the fabric of lived experience. “Computer Code Fabric” by Colleen Greene is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Digital and computational spaces are often positioned as beyond individual bias. Yet racialized and gendered discrimination persists in (ostensibly) disembodied networks; digital bodies are still marked with difference. Recent work on online identity formation (e.g. Andre Brock’s Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures), biased algorithms (e.g. Safiya Umoja Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism), and challenging the “neutrality” of data (Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein’s Data Feminism) reminds us of the ethical imperative to disrupt the illusion of data’s neutrality and decenter digital whiteness, masculinity, heteronormativity, wealth, and ability. In my own digital humanities and computational media pedagogy, I act on this ethical imperative in my selection of texts and methods.

This summer, teaching Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s work in my digital media and creative writing course was particularly timely: their stunning book Travesty Generator (2019) responds to the murders of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and countless other Black men at the hands of police. Bertram’s writing speaks directly to the contemporary #BlackLivesMatter protests that have been ongoing for years, but which finally permeated the national consciousness this summer as millions of people took to the streets. Bertram’s computational poetics maximizes the affordances of programming languages while also revealing and subverting their functionality. The poem “three_last_words,” for instance, meditates on algorithmic permutations of Eric Garner’s cry for help, “I can’t breathe.” In the “About” statement at the end of Travesty Generator, Bertram writes, “As an unimagined programmer, I use codes and algorithms in an attempt to create work that reconfigures and challenges oppressive narratives for Black people and to imagine new ones. I consider this an intervention into a set of [computational] literacy practices that have historically excluded women and minorities” (76). Following Bertram’s example, my students considered how critical and creative coding projects can disrupt “algorithms of oppression” (Safiya Noble).

To help students more fully understand Bertram’s Black computational poetics, I designed the syllabus to situate their work not only in the mostly white context of digital writing, but also in the context of formally and conceptually innovative African American poetics. Students interacted with Bertram’s computational poetry platform Forever Gwen Brooks (2019), which they describe as an “eternal and ephemeral…homage” to Gwendolyn Brooks’ monumental poetry. Bertram’s project remixes the final poem, “An Aspect of Love, Alive in the Ice and Fire,” from Brooks’ book Riot (1969), which meditates on the 1968 Chicago uprisings in response to MLK’s assassination. I wanted students to see how Forever Gwen Brooks highlights the historical and conceptual contexts of not only the resistance to anti-Black racism but also the celebration of Black liberation and joy. Reading Brooks with Bertram, students explored an analog-digital lineage of Black poetry that activates the political potential of experimental aesthetics. Interacting with the website, students were able to experience firsthand how Bertram’s project honors the beauty of Brooks’ poetry and infinitely generates new possibilities for the work to live on forever, as the line “It is the morning of our love” becomes “It is the fire of our America,” or “It is the blackness of our street,” or “It is the poem of our world.”

Influenced by Bertram’s work and other course texts (including Momo Pixel’s Hair Nah, Ramsey Nasser’s قلب, Sarah Ciston’s ladymouth, and LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs’ TwERK) that focus on race, gender, sexuality, ability, and other differences in digital spaces, many students chose to make projects exploring the political and aesthetic potential of computational media interventions. Several Indian American students made interactive Twine narratives about their experiences with racism and colorism, a perspective that further diversifies the minoritarian identities represented in Twine authorship. A hard-of-hearing student created an animated video about the power of love and acceptance using hand emojis to represent sign language; a Jewish student made a Twitterbot combatting anti-Semitism and racism more broadly. My hope is that these Georgia Tech students—all incoming freshman, mostly engineering or computer science majors—will continue to apply digital tools and methods to support the unending struggle for anti-racism and social justice.

“Monstrous History” by Kent Linthicum

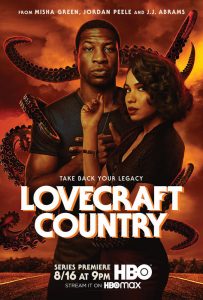

A promotional poster for Lovecraft Country (2020) by HBO.

One of the most unsettling parts of Lovecraft Country (2020) for me were two girls. Towards the end of the story one of the protagonists, Diana (or Dee), is cursed by a police officer to be stalked and killed by demons. These demons emerge, almost literally, from the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe. The demons are notable because while Stowe sought the end of slavery, she also codified and created some of the more persistent racist caricatures of Black Americans. Called Topsy and Bopsy, the demons chase Dee by erratically jigging and dancing after her. As Kinitra Brooks shows in her analysis—informed by the work of Rebecca Wanzo—these two girl-demons are versions of Topsy and Evangeline from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They represent visions of Black and white girlhood. Topsy and Evangeline are impossible visions though—too mischievous and too angelic respectively. No person could ever meet Topsy’s nadir or Evangeline’s zenith because the characters are not real. These characters hunt Dee, though, trying to force her to become one of them, which is analogous to the way media shapes the minds of real girls, pressuring them to meet one norm or another. This is about more than just media mangling girlhood; it is about the ways that slavery and the suffering of Black Americans continue to haunt us.

As a scholar of nineteenth century literature and culture, I consider slavery a ubiquitous and persistent influence on the texts I study. And, I have taught classes that grapple with slavery and its effects, such as my “Immoral Energy” course. I worry, though, as I assign historical texts on slavery, I am merely unleashing demons like Topsy and Bopsy on my students. In her pathbreaking work, Scenes of Subjugation (1997), Saidya Hartmann argues that it was not merely the exchange of enslaved Black Americans that defined slavery and antiblackness in the U.S., but the ways that Blackness as a category and through limitless violence was used to define whiteness. Christina Sharpe expands on this in In The Wake (2018) to show how Black life in the U.S. continues to reverberate with the effects of slavery and antiblackness. In Lovecraft Country, Uncle Tom’s Cabin falls off the shelf, lurching towards Dee and vibrating with antiblackness, violence, and white supremacy. Dropping Uncle Tom’s Cabin and other 19th century texts into my syllabi like that risks re-animating racist monsters which seek to reinscribe my students within their systems of violence.

Teaching slavery while not dredging up monsters from the past is a balancing act that I’m still working on. For me it means helping students understand the media ecology of text in the 19th century: the audience for these books were not enslaved Black people, but rather well-to-do white people. And in some cases, the books were either written or transcribed by white authors or editors. In these ways, the books still reinforce whiteness while trying to end slavery. So, I choose books that were written by Black authors, like Frederick Douglass’s Narrative (1845) or Harriet Jacobs Incidents (1861). I also emphasize different emotional registers than pain and suffering. For instance, a new favorite text of mine is William Wells Brown’s The Escape: Or, A Leap for Freedom (1858), a comedy about escaping slavery and fleeing to Canada. The drama offers up satirical vision of mid-19th century American politics. One character of note is Mr. White, a “citizen of Massachusetts” and an abolitionist. What’s amusing about White (besides his name) is that despite being opposed to slavery, he spends more time arguing with slaveholders than helping enslaved characters (Act 5, Scene 1). When given the opportunity to help an impoverished Native American in the North, he ignores them (Act 5, Scene 5). This caricature helps dismantle the myth that Abolitionists (or just those opposed to Southern slavery) were virtuous, moral warriors. For instance, as Ibram X. Kendi notes, even the famed Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison thought slavery “had ‘imbruted’ Black people” thus making “their cultures, psychologies, and behaviors inferior” to whites. Understanding the persistence of anti-Blackness in the United States means rethinking what 19th century abolition means today. As the other contributors to this article and other educators have shown, antiracist pedagogy is more than just choosing the right books and the barest historical context; it means rethinking our work altogether. This means finding ways of examining the racist monsters of our past, without releasing them upon our students today.

“Building a Resource Bank on Race and Policing at Georgia Tech” by Molly Slavin & Corey Goergen

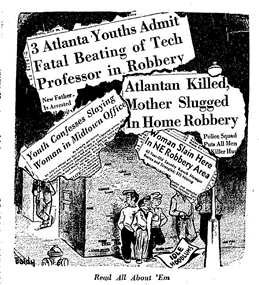

This cartoon, which appeared in the July 27, 1957 edition of The Atlanta Constitution, shows how the murder of a Tech professor played a role in urban renewal. PDFs of the cartoon, and related stories, are included in the Resource Bank.

In the fall of 2019, we taught linked courses on the topic of “Drug and Crime Epidemics.” During the semester, our classes discussed primary and secondary texts that show how, from eighteenth-century London to the present-day United States, people have used the specters of drug use and crime to control, oppress, and marginalize people. Most of the time, students engaged willingly in learning and interrogating this history, including some more difficult materials on mass incarceration and racist drug sentencing. But during one class period, we mentioned, in passing, that the interstates that cut through the city of Atlanta were intentionally routed to disrupt Black neighborhoods and maintain the boundary lines of segregation. Students pushed back. Though we were later, after the class and over email, able to provide resources for our students, like Kevin Kruse’s essay “How Segregation Caused Your Traffic Jam,” we found ourselves floundering in the moment, as we had not been expecting this to be the issue that students would not be willing to learn about. Part of this resistance likely occurred because mass incarceration is a much starker expression of white supremacy than city planning. But part of it seemed also due to the specificity of Atlanta. How could the interstate that marks the astern border of our campus perpetuate white supremacy?

This experience made us realize that specialized materials and resources tailored for Georgia Tech humanities teachers and scholars were urgently needed so that future instructors could be sufficiently prepared to address student responses, concerns, or questions, either through inviting open dialogue or by directing them toward additional resources. To that end, in our double roles as ENGL 1101/1102 instructors and members of the Curricular Innovation Committee, we spearheaded the creation of a Resource Bank focused on collecting materials on Black poetry, policing at Georgia Tech, and historical documents on portrayals of crime in the Atlanta area. The bank currently boasts an archive of primary sources on crime and the Georgia Tech Police Department; an open syllabus on campus police (developed in conjunction with the September 2020 #ScholarStrike); and a collation of “Poetry of Resistance and for Social Justice” (created by Wendy Truran, also for the #ScholarStrike). Molly provided the Resource Bank to her Fall 2020 ENGL 1102 students for their third artifact, which required researching either the Atlanta Police Department or Georgia Tech Police Department and arguing for or against reforming or abolishing the department; students reacted well to the material, engaging with it to support their arguments and expanding their knowledge on their local environment. One project in particular heavily utilized the Open Syllabus on Campus Policing to argue effectively for defunding the Georgia Tech Police Department. We encourage all those teaching classes related to the subject material to use and add to our burgeoning collection.

“Advocating for Antiracist Feminist Futures” by Bianca Batti

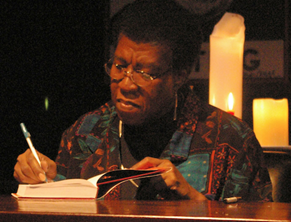

Octavia Butler signs one of her books during a book tour. Butler’s novel Dawn has been instrumental for my teaching of advocacy this semester. This image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license by Nikolas Coukouma.

Julia’s call, at the beginning of this piece, for academics to “create institutional change” by “[leaning] into our discomforts around conversations of race” resonates deeply with me, and I think this call warrants reiteration. Indeed, this idea of discomfort is vital to antiracist, feminist pedagogies—but what is also vital is reimagining discomfort as a productive space for inquiry, learning, and growth.

Samira Rajabi notes that, because feminist pedagogy requires students to acknowledge modes of oppression, students are thus asked to “enter a space of discomfort in naming this oppression so explicitly.” However, constructing the classroom as a space of discomfort is productive pedagogical practice because it “offers fertile ground on which to plant seeds of knowledge” as long as such feminist pedagogy allows students to directly position themselves in relation to systems of power “in and through their own political and social locations.”

This mode of positioning oneself within a pedagogical space of discomfort is something I consistently encourage my students to do (and is, to be sure, something that I consistently require of myself as well as a practitioner of feminist theorizing). This zone of discomfort affords students a productive space in which to learn because such discomfort requires them to dig deep—to consider the cause and significance of their discomfort—in order to then resolve it. Indeed, I construct my classroom, in part, as a space of productive, transformative discomfort because doing so is a manifestation of my antiracist, feminist pedagogy and praxis.

I have been teaching an ENGL 1102 course this fall entitled “Science Fictional Futurities: (Re)Imagining the Future of Creation, Communication, and Technology,” in which students have been interrogating the ways science fictional texts imagine the future; in doing so, students have been drawing from such frameworks to reimagine their own futures as communicators, creators, and users of technology. We have specifically been implementing antiracist, feminist, and social justice lenses when examining SF texts like the film Ex Machina and the comic book series Paper Girls.

The idea of sitting in a productive space of discomfort when engaging with SF became especially important during the second unit of our course, during which we read Octavia Butler’s novel Dawn (1987), a work of black feminist science fiction. Concurrently, students were tasked with designing an advocacy infographic (an assignment that I learned how to teach as a PhD candidate and teaching assistant for ICaP, the introductory composition program at Purdue University). In this assignment, students chose a topic inspired by the social, political, and ethical questions raised in Dawn, then advocated for and presented it to a public-facing, digital audience of their choosing in order to mobilize that audience to action.

Because Butler’s science fictional future in Dawn examines racism, sexism, gendered violence, imperialism, environmental issues, the ethics of genetic engineering, and more, students chose from numerous potential topics. And because Dawn’s protagonist, Lilith, must advocate for the survival of the human race to multiple (sometimes alien, sometimes human) audiences, Dawn also provided students with rhetorical strategies and models for their own advocacy-oriented work. Finally, because of the context surrounding our class, which also informed students’ engagement with Dawn, many of my students chose to advocate about topics like #BlackLivesMatter, police brutality, and voter suppression, while others chose to advocate about the gender spectrum, climate change, renewable energies, and intimate partner violence.

In the instructional videos and discussion forum prompts that I also provided students during this work, I explicitly discussed the role discomfort played in our processes, thinking, and discussions during that unit. That is because Dawn—just like so much of Octavia Butler’s fiction—requires discomfort from its audience. Indeed, in my instructional videos, I asked students to sit in that discomfort, to ask themselves what made them feel uncomfortable when reading Dawn, and to interrogate, specifically, some of the hegemonic, white supremacist, patriarchal structures that contribute, ultimately, to their discomfort.

In doing so, my hope (in keeping with my course’s theme) has been to allow students to (re)imagine discomfort as a productive space for learning, not just in our class, but more broadly as well. I believe as my colleagues’ work here demonstrates that antiracist pedagogy is needed so that both students and teachers can work toward cultural, communicative, and institutional change in writing and communication courses.

Following the death of George Floyd, the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery (MAAHMG) commissioned a block-long mural painted on the surface of Plymouth Avenue on the North Side. 16 artists each filled up one letter in the phrase ‘BLACK LIVES MATTER’. “Aerial view of Black Lives Matter mural at Penn and Plymouth” by August Schwerdfeger is licensed under CC BY 2.0.