Dr. Nick Sturm’s “Poetics of Sustainability” students weeding strawberry patches at Aluma Farm on the BeltLine’s Westside Trail, June 2019.

Frankenstein in alternative genres, freshly redesigned periodic tables, poetry and digital archives, feminist editorial interventions in Wikipedia, sustainable futures, pop culture, and crisis—these are the Writing and Communication course topics that Brittain Fellows experimented with in the 2019 summer semester at Georgia Tech. The compressed six-week course schedule and opportunities to collaborate with the iGniTe Summer Launch Program—an early admission initiative—and Serve-Learn-Sustain (SLS)—the Institute’s program for training students in equitable and sustainable development, service learning, and other topics—offer a range of ways to develop our multimodal pedagogy. These seven reflections on our recent summer teaching serve as examples of the Brittain Fellowship’s use of tools and assignments that innovate on humanities-based pedagogies in a range of transdisciplinary contexts.

Designing Periodically in ENGL 1102

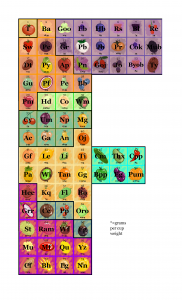

A Fruity Table, designed by Asia Taylor, Diana Kim, Angel Hsieh, Corinna Alting, and another classmate

A ubiquitous symbol of chemistry and the physical universe, the Periodic Table is multimodal, utilizing the Written, the Visual, and the Nonverbal modes to translate scientific principles and concepts across cultures. Knowing 2019 is designated the International Year of the Periodic Table, I created my Summer 2019 ENGL 1102 course topic, “Invention, Exploration, and the Elements: The Rhetoric of Science from the 18th Century to Today,” with the idea of challenging students to produce their own periodic tables.

We began the term by reading Sam Kean’s The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements (2011). Kean describes twists and turns of the elements’ various discoveries, elucidating how the organizing principles of the Table’s iconic columns of blocks predict properties of adjacent elements. Important for our class was the notion that each symbol has specific meaning, each column signifies particular identifying principles, and each item of alphanumeric text speaks to the Table’s readers. The Periodic Table’s every factor was chosen for its rhetorical significance.

The Periodic Table of Wands, designed by Sean Alexander, Joe Glover, Zachary Myers, and another classmate

Students collaborated to design periodic tables for Artifact 3. After choosing “elements,” they decided based on their specific rhetorical situation how best to communicate visually their organizational principle. The Periodic Table has a wide-ranging audience, posted as it is in Chemistry classrooms and labs across the world; who would be interested in their topic? On the Table, a one- or two-letter symbol immediately differentiates carbon (C) from cobalt (Co) or chlorine (Cl); would color and image be similarly effective in visually identifying individual “elements” on their table? Proximity is crucial for the Table’s design: noble gases occupy the far right column, while lanthanides and actinides reside below the main table to indicate their properties unique from surrounding elements. How might students arrange their “elements”?

Armed with these considerations among others and a tutorial in InDesign provided by Alison Valk, students proposed their project plan, composed artists’ statements reflecting on their design choices, and created their tables. Two of those tables, “A Fruity Table” and “The Periodic Table of Wands,” are pictured here. “The Periodic Table of the Pomme de Terre” designed by Carson Clements, Natalie Raia, and two classmates, is viewable as a Prezi here.

Editors’ note: See the GT College of Science’s story about Dr. Hoffman’s course, “First-Year Students Create Their Very Own Periodic Tables.”

—Courtney Hoffman, 3rd Year Brittain Fellow and Assistant Director of the Writing and Communication Program

An Audience of 500 Million: Editing Wikipedia as a Writing Assignment

How can we help our students feel that their work in the writing classroom matters? Students struggle to see the point of crafting meticulous assignments when their work ultimately reaches an audience of one. Instead, this summer, I challenged my students to write for an audience of 500 million.

English-language Wikipedia is the fifth most-visited website in the world, averaging 18 billion pageviews per month. It frequently appears on the front page of Google searches. If you ask Siri, Alexa, or Google Home a question, chances are the answer comes from Wikipedia. This global reach, combined with the encyclopedia’s model of open collaboration, makes it a uniquely challenging and rewarding teaching tool. Anyone can contribute to Wikipedia, and those contributions will be seen by an almost unthinkably large audience.

The Wikimedia Foundation recognizes the pedagogical promise of Wikipedia. Through WikiEdu, they offer teachers robust sets of trainings, assignments, and tools to help integrate Wikipedia editing assignments into classrooms.

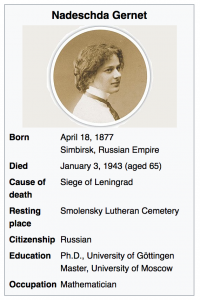

I’ve experimented with asking students to edit Wikipedia in the past, but this summer, I decided to build an entire six-week intensive composition course around the project. In our class on “Writing Women Back into STEM History,” students chose a historical woman who worked in a STEM field but was not yet represented by a biography on  Wikipedia, and they set out to contribute a complete article about her.

Wikipedia, and they set out to contribute a complete article about her.

Each of our assignments helped students prepare for the daunting task of writing for 500 million potential readers. First, they compiled a collaborative annotated bibliography, full of sources they could mine for information and cite in their eventual articles. As they researched, they made use of WikiEdu’s training modules to learn how to craft and format their contributions to meet Wikipedia’s standards. They peer reviewed each other’s drafts and presented their research orally, sharing in story form all of the fascinating and world-changing projects their women had worked on. Finally, they submitted their work as draft articles to Wikipedia’s more experienced editors for final approval.

It was a thrill when, days before their final deadline, we discovered that one student’s article had already passed review and was live on the site. As of this writing, 11 of my students’ articles, representing almost 13,000 words and 208 citations, have been approved and are live on Wikipedia.

In their final reflections for the course, students commented that contributing to Wikipedia helped them think about audience and voice in ways they never had before. “The stakes seemed higher than usual,” one student wrote. “It made [the assignment] feel important and impactful.”

—Alexandra Edwards, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Sustainable Summer Futures

Quarry Yards development in West Atlanta across from Bankhead MARTA Station.

I engaged with the iGniTe summer program by teaching a modified version of a regular semester ENGL 1102 class called Back to the Future. Over the course the six-week session, students and I analyzed visual and written renderings of idealized futures, such as artist renderings of Atlanta redevelopment projects and Thomas More’s Utopia, to identify relationships across ecological, social, and economic systems. In addition to examining the ways that the concept of futurity helps us see how the social, economic, and ecological are always interrelated in conservation efforts across time, I invited my students to create their own futures through a creative world building project.

Step One: Threat Diagnosis

The first step of the creative world building project is diagnostic. Specifically, I have students respond to the following question in a 300-500-word low stakes writing assignment: what do you think poses the greatest threat to the continued existence of life on Earth and why? After students generate a range of existential threats, such as unchecked carbon emissions, overpopulation, nuclear war, drug-resistant bacteria, and mass extinctions, we move onto a second step in which I ask them to imagine a world in which the threats they diagnose have been redressed.

Step Two: Creative World Building

Once students reflect on their proposed solutions, I ask they to move into drafting their worlds. During this second step, I guide students through an exercise that I developed by combining the categorical thinking that More lays out in his Utopia with N.K. Jemisin’s Master Class in World Building. Over the course of a class session, and guided by a handout, students describe how their future worlds redress the existential threat they outlined across the following categories: Government, Economy, Religion, Education, Geography, Transportation, Agriculture, Reproduction, Identity, Medicine, Sex/Gender, Marriage, and Technology.

Step Three: Developing Connections

After students have drafted a future free from the threat they diagnosed during the creative word building session, I ask them to develop and finalize their drafts by explaining how each of the social, economic, and ecological categories they describe relate to one another. In other words, the goal of the final draft of the assignment is to show what happens to all of the elements in an interrelated system when one element changes. For instance, if a future world of their invention redresses unchecked carbon emissions by outlawing cars, does that mean that cities would be built differently or that education would emphasize the community over the individual? The final draft of each future world functions as a proof of concept, which students illustrate through written description and visual rhetoric, designed to persuade audiences of the ways in which the social, economic, and ecological are always interconnected.

—McKenna Rose, 3rd Year Brittain Fellow and Assistant Director of Assessment

Afterlives of Frankenstein

Two-hundred and three years ago on a dreary night in June, Mary Shelley imagined a “pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together […] the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” Two years later, she would publish Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus (1818), arguably one of the most influential and popular science fiction novels ever. The novel has long fascinated me (specifically due to the conditions under which it was composed). Given the novel’s importance—especially its reflections on science and technology—I thought it would be a good fit for the iGniTe program.

The brevity of summer classes make them excellent spaces for in-depth examinations of singular topics. By focusing on Frankenstein and its progeny, my class was able to develop a robust understanding of the novel’s themes while also practicing multimodal composition. For example, in one project, students were tasked with scrutinizing an adaptation of Frankenstein and evaluating it through a presentation. To start this project we watched the first film adaptation of the novel, created by Thomas Edison’s movie studio:

Above: Frankenstein: A Liberal Adaptation from Mrs. Shelley’s Famous Story for Edison Production (1910)

That film provoked a range of reactions, especially for its remarkable special effects and its substantial changes to the plot. This start (and a pile of drafts and peer review notes) lead to excellent student presentations, like one evaluating the multi-media adaptation, Frankenstein, M.D. (2014), and the ways that adaptation used new communication technologies to dramatize the two-hundred year old story.

I asked my students to do something similar for the final project, re-imagining Frankenstein for the 21st century on a website. One of the best projects dramatized the impacts of social media, asking what would happen if the Creature were educated via Instagram rather than Paradise Lost. Overall, the class’s narrow, single-novel focus worked quite well for the iGniTe program and received positive responses from students: “I do not know if I would have ever read Frankenstein […], but I thoroughly enjoyed the book and analyzing the themes in the 21st century. This class has very much represented what Georgia Tech is about: how science and technology relate to every aspect of our life and future.”

—Kent Linthicum, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Rhetorics of Crisis

In the summer of 2019, I taught ENGL 1101, “Rhetorics of Crisis,” as part of the iGniTe summer program. I received a course development grant from Serve-Learn-Sustain for an ENGL 1102 course I am scheduled to teach in Spring 2020 (this course will also be titled “Rhetorics of Crisis”). This is a brand-new course and research area for me, so I needed to develop everything from scratch. The grant affiliates my course with Serve-Learn-Sustain and comes with funding to hire guest speakers or pay for out-of-classroom activities that directly link to my course topic. Though I did not receive specific funding for the Summer 2019 course, and the dense six-week schedule meant it would have been difficult to make use of the funds in a meaningful way, I decided the summer iGniTe course would be a perfect venue through which to test drive “Rhetorics of Crisis” before the Spring 2020 full-semester course.

In the summer of 2019, I taught ENGL 1101, “Rhetorics of Crisis,” as part of the iGniTe summer program. I received a course development grant from Serve-Learn-Sustain for an ENGL 1102 course I am scheduled to teach in Spring 2020 (this course will also be titled “Rhetorics of Crisis”). This is a brand-new course and research area for me, so I needed to develop everything from scratch. The grant affiliates my course with Serve-Learn-Sustain and comes with funding to hire guest speakers or pay for out-of-classroom activities that directly link to my course topic. Though I did not receive specific funding for the Summer 2019 course, and the dense six-week schedule meant it would have been difficult to make use of the funds in a meaningful way, I decided the summer iGniTe course would be a perfect venue through which to test drive “Rhetorics of Crisis” before the Spring 2020 full-semester course.

I designed my ENGL 1101 version of “Rhetorics of Crisis” to be a preview of the Spring 2020 1102 version, with more reading to make up for the lack of guest speakers and experiential learning opportunities. I divided the class into three units: “Synthesizing Crisis Rhetorics,” “Race and Policing,” and “Refugees, Terrorism, and War.”

I am overall quite happy with the way the summer course went. The division of the course into three units worked, and the “Race and Policing” unit was especially well-received. I think in order to be able to draw in the resources of the local community, however, I will need to redesign certain aspects of the course for the Spring 2020 version; I will probably replace the first generalized unit with a specific unit on climate change in order to connect with environmental groups in the area, and I will select different readings for “Refugees, Terrorism, and War” in order to connect with Atlanta organizations, such as Friends of Refugees in Clarkston. Overall, summer teaching was a great venue to try out a new course topic, and I would recommend it as a way to dip your toes into areas that may be new to you.

—Molly Slavin, 2nd Year Brittain Fellow

Five Weeks of Intense Pop Culture

For the last few years, my ENGL 1101/0999 courses have been a 15-week long process of creating an individual graphic memoir. There’s a great deal of scaffolding and a lot of reading that goes along with this project in order to convince students that they can, in fact, create a successful comic with limited artistic ability (trust me, they can). However, when faced with my first ENGL 1101 summer course in a few years, I realized there was no way to do the in-depth work of the Autobiographical Graphic Novels course in just five weeks. What I needed was a topic that could draw on existing student knowledge to create engaging multimodal assignments without a super intensive reading schedule. The solution to this came in the form of the recently published textbook Popular Culture in the US: People, Politics, and Power by Jenn Brandt and Callie Clare (both grads of my PhD institution). The book offers an overview of theories of media analysis which students could then apply to things they already knew and enjoyed (or hated). Rather than finding an artifact (say, a graphic novel) for student to analyze, they brought their own interests and experiences to the classroom and used our discussions to advance arguments about their interests. I got projects on the Trap Music Museum in Atlanta, car meet culture, the importance of music in video games, horror movies (so many horror projects!), and YouTube influencers. This was great, because I know basically nothing about any of these topics, besides the lenses of analysis that we were using.

For the last few years, my ENGL 1101/0999 courses have been a 15-week long process of creating an individual graphic memoir. There’s a great deal of scaffolding and a lot of reading that goes along with this project in order to convince students that they can, in fact, create a successful comic with limited artistic ability (trust me, they can). However, when faced with my first ENGL 1101 summer course in a few years, I realized there was no way to do the in-depth work of the Autobiographical Graphic Novels course in just five weeks. What I needed was a topic that could draw on existing student knowledge to create engaging multimodal assignments without a super intensive reading schedule. The solution to this came in the form of the recently published textbook Popular Culture in the US: People, Politics, and Power by Jenn Brandt and Callie Clare (both grads of my PhD institution). The book offers an overview of theories of media analysis which students could then apply to things they already knew and enjoyed (or hated). Rather than finding an artifact (say, a graphic novel) for student to analyze, they brought their own interests and experiences to the classroom and used our discussions to advance arguments about their interests. I got projects on the Trap Music Museum in Atlanta, car meet culture, the importance of music in video games, horror movies (so many horror projects!), and YouTube influencers. This was great, because I know basically nothing about any of these topics, besides the lenses of analysis that we were using.

Another important element of the class was to have students create pop culture artifacts themselves, rather than the formal analysis essays they were more familiar with from high school. Students created a YouTube video on cultural myths and some aspect of pop culture, a group podcast on how a given artifact fits into a genre, and a choose-your-own genre written analysis exploring identity in a pop culture text (following the model Chapter 24 in the WOVENText on Revising & Delivering Your Project). Each project had all the process elements that we strive for in our full-semester classes (brainstorm, draft, revision, edits, publication, reflection) and students commented about the success of that process oriented communication structure often in their final portfolios. The most successful way to do this, I found, was to use reading responses as brainstorm moments and then build to final drafts with a lot of time in class devoted to process work. In order to make sure that process work was productive there were always small Canvas assignments to complete at the end of a work period. This gave me more of a chance to give feedback or intervene if a project was going off course, and it also gave students lots of evidence to use when compiling their final portfolios. There are definitely minor changes that I would like to make before I teach this course again, but of the three 1101 summer classes I’ve taught at Tech, I’m certainly the happiest with this one. Keys to success: short readings, lots of small steps, drawing on student interests, and giving consistent feedback!

—Rachel Dean-Ruzicka, Lecturer and Former Brittain Fellow

Exploring the Ivan Allen Digital Archive

I love teaching in the iGniTe Summer Launch Program, an opportunity that has allowed me to collaborate with Serve-Learn-Sustain (SLS) for the past two summers on a course called “The Poetics of Sustainability.” The instant sense of community among these energetic iGniTe students, the collaborative and out-of-class opportunities offered by SLS, and the intensive, compressed schedule make summer teaching at Tech feel like an experimental summer camp full of poetry, museum visits, volunteering at urban farms, and a litany of innovative student-led multimodal research projects. For example, last summer after reading books of poetry by Raúl Zurita and Divya Victor about the intersections of diaspora, nationalism, and political oppression, my students were trained as volunteer court watchers by the Innovation Law Lab and Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative. They then attended immigration hearings at courts in Atlanta, the area of the country with the lowest rates of approved asylum cases, to report observed courtroom bias in sworn affidavits, an experience that deeply affected both my students and myself and re-inscribed the urgency of communicative acts—like in a courtroom in a foreign country—upon which someone’s future and safety might hinge.

Collaborative student website on the Summerhill Riot in Atlanta.

This summer’s “Poetics of Sustainability” course focused on issues of race and environment and brought students to the urban Aluma Farm on the BeltLine Westside Trail in Atlanta’s Adair Park neighborhood, the Center for Civil and Human Rights, and—in connection with researching the Ivan Allen Digital Archive—to sites around Atlanta where students research into the city’s history in the 1960s via the digital archive could come to life, all while reading books of poetry such as alphabet by Inger Christensen and Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine. This research project asked students working in groups of five to utilize the Ivan Allen Digital Archive to produce artifacts that explore major historical issues of racial and environmental inequity during Mayor Ivan Allen Jr.’s tenure as the 52nd Mayor of Atlanta (1962-1970). The Ivan Allen Digital Archive is a digital archive hosted by Georgia Tech since 2016 that contains over 10,000 documents related to Allen’s mayoral tenure including a range of important material related to civil rights, housing policy, urban renewal, mass transit, discriminatory policing, and environmental injustice.

Students present their Ivan Allen Digital Archive project on the pollution of Proctor Creek at the iGniTe Summer Showcase.

While operational, the Ivan Allen Digital Archive has yet to be widely utilized in Georgia Tech classes. Students created websites that focus on one of the three major issues addressed in the archive—the Summerhill Riot of 1966, Mayor Allen’s support of the Civil Rights Act, and the pollution of Proctor Creek in Atlanta’s Westside neighborhoods—in order to contextualize and create accessibility to the digital archive for scholars, activists, and community members interested in the history of racial and environmental inequity in Atlanta. These sites serve as well-designed multimodal examples of research-based student use of the archive that will facilitate future support of the archive’s development and sustainability. Students finished the semester by formally presenting their Ivan Allen Digital Archive projects at the iGniTe Summer Showcase event. Their websites were a hit with the iGniTe Summer Sessions Team and their peers, especially the pollution of Proctor Creek group that brought a pile of garbage—including a muddy car tire—that they had pulled from the creek the day before. These incredibly persuasive props acted as tangible material evidence of the ongoing neglect resulting from what their project describes as “the bureaucratic response” to Proctor Creek’s degradation in the 1960s that “showed little urgency or interest in utilizing governmental resources to address the issue.” I’m looking forward to 2020’s iGniTe program to continue to connect first-year students to these vibrant intersections of poetry, history, and culture in our city. As one student reflected, “This class has been an eye-opener for the contemporary issues that we face today that have roots in the past.”

—Nick Sturm, 3rd Year Brittain Fellow