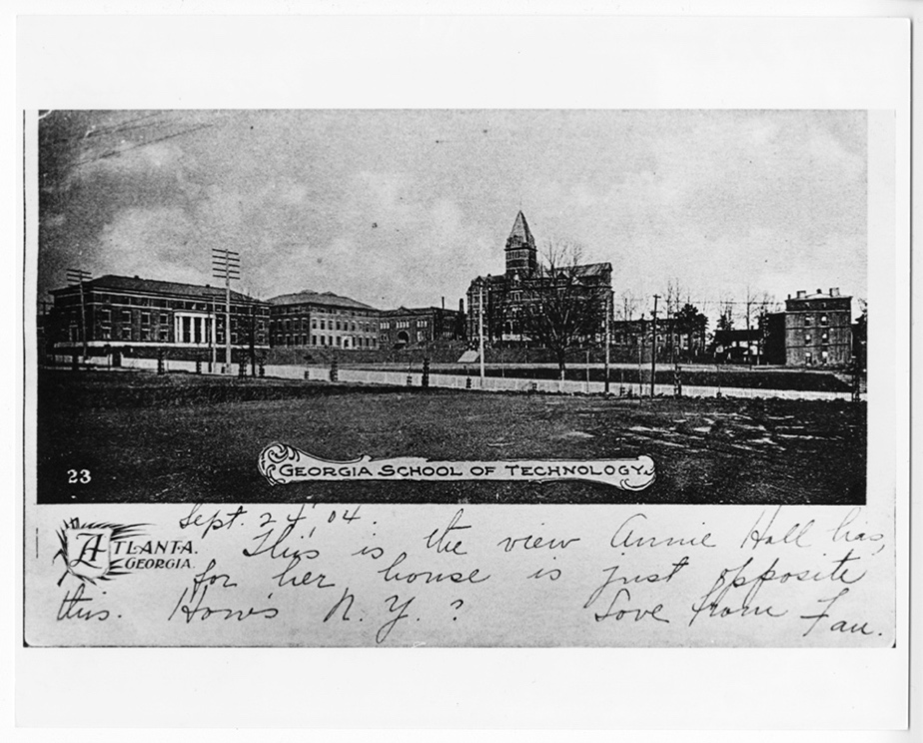

Postcard dated September 4, 1924. Caption reads “This is the view Annie Hall has, for her house is just opposite this. How’s N.Y.? Love from Fau.” Document preserved in the Georgia Tech Photograph Collection.

By Danielle Gilman

Is it possible to feel a sense of belonging to a place you’ve never been? I grappled with this question quite often last summer as I prepared to teach three sections of my “Archival Narratives” course to a cohort of students who had, by and large, never stepped foot on Georgia Tech’s campus. Nearly all the students enrolled in my English 1101 courses last fall were first-semester freshmen scattered across states and countries. Many had, as they would later share in virtual BlueJeans calls and online discussion boards, committed to Tech sight unseen—no campus tours, no meandering around the bookstore, and no opportunities to explore the city of Atlanta.

At the time, the question was a personal one as well. I committed to join the new cohort of Brittain Fellows last July while still in quarantine. Though I was already based in Georgia, Tech’s campus—along with its traditions, buildings, and culture—was just as much of a mystery to me as it was to my students. I knew little about the research and innovation that led to the development of the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design; I was admittedly startled when I first heard the steam whistle while walking to my new office; and I’ve always stood on the Athens side of the Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate rivalry. My students and I lacked familiarity with our campus—the sort of familiarity that comes only after you’ve spent weeks, months, and years exploring a place. We had no favorite seats in the library, no fond memories of sitting on Tech Green, and we shared an imprecise notion of what specifically we should miss. Endemic to prolonged periods of remote instruction seems to be an acute sense of dislocation. My students and I struggled to visualize the details of campus—yet we spoke often about the places we each wanted to visit once conditions allowed.

Despite a general sense of pandemic-related malaise when my students and I first began to meet remotely in August, there were practical matters to attend to as well. My courses were both remote and asynchronous, and so the “Archival Narratives” course that I had once envisioned as an introduction to primary source research and writing via hands-on work in the Georgia Tech Archives & Special Collections required considerable modification to suit this modality. I arranged with archival educators at the Rockefeller Archive Center to film guest lectures on archival best practices and to share with students from an archivist’s perspective the value of digitizing material objects and related ephemera during the pandemic. I worked with archivists and library staff at Tech to share similar resources during our early lectures on and discussions about the differences between, say, a personal archive and a research archive. I spent quite a bit of time, too, scouring the holdings in our collections and in private archives to determine what primary source materials would be easily accessible to my students throughout the semester. For the purposes of my course, “easily accessible” meant items would be available to students with a gtID# or would be available as open-access resources online. I did not want my students to purchase access to any databases, and I also prioritized using resources that were downloadable so that students lacking reliable access to Wi-Fi, for example, could download the materials once and be assured access later on.

Ken Prince described in a recent photo essay, “When Campus Closes,” the considerable “behind-the-scenes” work required of faculty, university staff, and even students as they shifted to emergency remote instruction during the onset of the pandemic (290). I spent most of the summer making these adjustments and additions to my lesson plans, major assignments, and Canvas pages. My colleagues continued to spend innumerable hours in an effort to make hybrid and remote instruction safe and accessible to their students as well. Staff from the Naugle Communication Center, for example, shifted consultations to a digital space in spring 2020, and they continue to support students via face-to-face and remote sessions this year as well. Faculty in the Writing and Communication Program strategized best practices for teaching outside (dress accordingly; focus on small group discussion; be generous to your students and to yourself) and similarly continue to support students with innovative and engaging pedagogy.

For my own classes, I knew that I wanted to spend our semester exploring the relationship between the archive and narrative construction. How do different types of archives function? How can we use the materials contained therein to share stories about ourselves and our communities? As an instructor and researcher with particular interest in digital learning and archival studies, I was also eager to study the increased digitization of primary source materials during the pandemic. What are the short-term and long-term effects of technology on the archive and on our methods of research, writing, and communication? The pandemic occasioned adjustments to my pedagogy that have, on the whole, enabled me to think productively about these questions—about how the relationship between these two fields of study creates meaningful conversations and connections and how I can represent to my students the value of hands-on engagement with primary sources and archival research even when that work must occur remotely.

In what follows, I share an assignment from my “Archival Narratives” course that was designed to help my remote and asynchronous students learn more about our new campus, as well as achieve the following objectives:

- Bridge the gap between the remote classroom and the archive.

- Navigate online databases.

- Parse primary sources.

- Construct a written narrative supported by archival research.

I share this assignment and some of my students’ work to model how the archive can be a productive, accessible tool in remote and asynchronous courses. I initially hesitated to attempt this course theme in a fully remote and asynchronous environment because I worried that the distance from the physical archive would diminish the value of these projects and discussions. However, it has been my experience over the last year that using digital and digitized archival resources encourages students to develop new and innovative ways to engage with primary sources, complete original research, and strengthen their digital literacy skills.

The (Remote) Place Narrative

My students completed three major projects or “artifacts” during our fall semester. The first, an object narrative, tasked students with researching the history of a material object and sharing their findings on a public-facing WordPress site styled after the “Object Lessons” series in The Atlantic. The second artifact, a personal narrative inspired by our discussions on personal digital archiving, required students to create a podcast narrative about their decision to attend Tech. For their third and final artifact, students worked in teams of five to compose a place narrative. This artifact encouraged students to research and share the history of a building on campus and then consider a change they might make to that space. Last fall, the groups across my three sections chose a variety of campus landmarks: the Kendeda Building, the Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons (or, as my students taught me, the “CULC”), the Campus Recreation Center (similarly shortened and affectionately termed the “CRC”), Bobby Dodd Stadium, and Tech Tower.

It is worth noting that this project required students to embark on a reasonably ambitious research mission. Collectively, they sourced, analyzed, and cited dozens of archival documents before even beginning to construct the longer written component of the project. I believe the research process was smoother at the end of the term because students had the benefit of a semester’s worth of discussions related to the fundamentals of research, archival research, and collaborative work. They had already spent time accessing and using online databases and had also learned from several guest experts in the field. I considered during my initial planning for the course that the assignment might be well-placed at the start of the semester. If I wanted my students to learn more about our campus and its history, it would seem an appropriate introductory project. However, this project targets specific research skill development: students navigate online databases hosted by university archives and private archives; they collaborate to perform visual analyses on primary source documents; and they catalog their findings in a shared Dropbox that is organized according to earlier discussions on archive and record management. In light of these goals, the project was ultimately better suited as a concluding assignment.

A view from the front of the Carnegie Building, c. 1920. Beneath the image, an unattributed poem reads: “Back again in dreams I wander / To the times that used to be. / When within Tech’s portals dwelt / My friends all dear to me.” Document preserved in the Georgia Tech Photograph Collection. (Click on image to see enlarged view.)

Once the groups decided on their locations, they began completing archival research via two digital research portals: the Georgia Tech Archives Digital Portal and the Digital Library of Georgia, an initiative started by the University System of Georgia in an effort to “provide not only digital facsimiles of historical and cultural materials, but […] to include rich background, contextual information, description, and metadata to promote deeper analysis and greater understanding of the collections and materials.” After compiling their initial research portfolios, each group began work on the artifact’s main deliverable: a persuasive letter addressed to the university’s Design and Construction Department proposing an improvement to their chosen building—ideally an improvement to benefit current and future students alike. The letter needed to share with its recipients the rich history of the building, as evinced in the collection of documents attached to their proposal, while also making a succinct argument for their proposed improvement. As I mentioned, because many of my students were completing the project while living away from campus, their research efforts engaged exclusively with born-digital and digitized source material. We’d spent time earlier in the semester discussing the differences between born-digital and digitized sources, so students were prepared to access and work with a variety of materials. To learn more about their building’s current role and any potential improvements that might be needed, for example, they scoured our university website; they read Reddit posts; they polled classmates who happened to be on campus or in Atlanta; and together they began to construct more complete narratives.

Their final submissions were well-researched and compelling. One group examined the history and development of Tech Tower. The group commented on the value of maintaining this visible campus landmark but proposed the addition of a digital exhibit inside of the building so that prospective students, current students, and visitors to campus might learn more about its storied history and view a curated set of digitized archival documents. Did you know, for example, that Tech Tower is in fact named the Lettie Pate Whitehead Evans Administration Building? Whitehead Evans established the Whitehead Holdings Company and Whitehead Realty Company to independently manage her family’s business interests and assets after her husband’s death in 1906. In 1945, Whitehead Evans founded the Lettie Pate Evans Foundation in an effort to further her philanthropic efforts, and the foundation supported a variety of cultural institutions in Georgia.

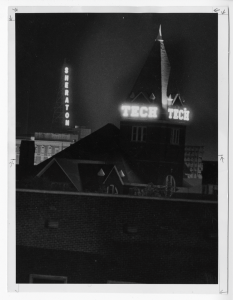

An undated image of Tech Tower with a Sheraton Hotel visible in the background. Document preserved in the Georgia Tech Photograph Collection. (Click on image to see enlarged view.)

My students emphasized the potential value of sharing with the Tech community more information about the building’s titular businesswoman philanthropist as she is currently described on our university’s website only as “one of the Institute’s most generous benefactors.” I share below three images from the group’s final submission.

In addition to projects designed to promote greater cultural and historical awareness on campus, students also turned their attention to proposals intended to improve student experience at Tech. One group studied the construction process on the CULC and used a collection of building plans and images to argue for a redesign of larger areas of open space to include additional seating for students who would like to safely spend time inside the building while social distancing. Another group took on the daunting task of proposing a change to the Kendeda Building—arguably the newest and most innovative space on campus. After a thorough account of building schematics, maps, and press releases from the construction process, the students proposed several improvements to the space. In particular, the group noted the building is marketed on its website as the product of a “truly sustainable program” intending to provide “a welcoming, accessible, nature-based environment” to campus and community members. However, aside from guided tours, there are currently few opportunities for members of the local community to take advantage of the building’s resources and events hosted onsite. The group thus proposed enacting a policy to livestream all lectures and workshops held in the building in an effort to make this space and its resources more widely accessible and thus more in line with its published aims and values.

Conclusion

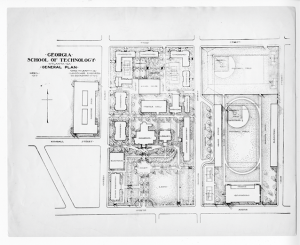

Campus plans for the Georgia School of Technology, c. April 1912. The “Academics,” or Tech Tower, is visible at the center. Document preserved in the Georgia Tech Photograph Collection. (Click on image to see enlarged view.)

When I first assigned this project to my students, I posed to them the same question that troubled me all summer: Is it possible to feel a sense of belonging to a place you’ve never been? I worried that this remote version of the project would be a poor substitute for archival research done in a traditional archive. Would examining a series of primary source documents make our campus seem any more familiar to students signing into our class from hundreds or even thousands of miles away? There have been very few certainties for those of us teaching during the pandemic; each tool we use in the remote classroom seems to have some limitation. I am not altogether certain that an assignment like this can truly lessen the disconnect students feel from campus while taking on remote coursework. I am, however, encouraged by the research and analytical skills students modeled while working together on this artifact. So, is it possible to feel a sense of belonging to a place you’ve never been? A month after our class ended, I received an email from several students who had worked together in a group on this artifact. They wrote to tell me that they’d met up in person earlier that day “to visit our building” and confirm that their proposal for an improvement to the space was in fact a sound one. I read their email and considered that the answer to my question might just be yes.

Works Cited

“Campus plans,” Georgia Tech History Digital Portal, accessed April 11, 2021, https://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/1370.

“Campus scene [1413],” Georgia Tech History Digital Portal, accessed April 1, 2021, https://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/1413.

“Campus scene [1415],” Georgia Tech History Digital Portal, accessed April 1, 2021, https://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/1415.

“Digital Library of Georgia: Mission, Guiding Principles, and Goals.” Digital Library of Georgia, dlg.usg.edu/about/mission.

“Equity Petal.” The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, https://livingbuilding.gatech.edu/equity-petal

Prince, Ken. “Photo Essay: When Campus Closes.” CEA Critic, vol. 82 no. 3, 2020, p. 290-296. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/cea.2020.0024.

“Tech Tower [2365],” Georgia Tech History Digital Portal, accessed April 7, 2021, https://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/2365.

“Tech Tower [2366],” Georgia Tech History Digital Portal, accessed April 3, 2021, https://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/2366.