This article and interview are a collaboration between Dr. Benjamin Bergholtz and Dr. Alok Amatya, first-year Brittain Fellows in the Writing and Communication Program at Georgia Tech, and FYC students Gabriel Wang, Harsimran Minhas, Simrill Smith, Justin Coleman, and Kartik Sarangmath.

I didn’t think I would be able to to write about my students’ reactions to reading strange, sprawling novels in my Fall 2018 English 1102 course, “Big Books: Why Bother?” Well, that’s not quite true. I knew that I could analyze my students’ reactions to reading the two “big books” of the course—Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) and Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014)—but I wondered whether or not I was the one who should conduct this analysis. As I am currently writing a book about why readers do “bother” with maximalist novels—as they are often called—I worried that my view of my students’ experiences with these novels would be partial.

In discussing this fact with my friend and fellow first-year Brittain fellow Alok Amatya, we came up with a solution: we would let the students speak for themselves about the class, and we should have someone with whom they are not familiar—that is, Alok—facilitate the discussion. Alok agreed to generate questions, and I enlisted five students representing a broad cross-section of the course—Justin Coleman, Harsimran Minhas, Kartik Sarangmath, Simrill Smith, and Gabriel Wang—to participate in the interview.

While the conversation below addresses several aspects of the course, it primarily revolves around our final artifact, a digital project I called “Mapping the Maximalist Novel,” which challenged students to consider and illustrate the transnational movement of characters or commodities in maximalist fiction. The conversation revolves around this project for a fairly simple reason: the students and I agreed that it was, by far, the most successful tool for helping them to engage with the historical, formal, intellectual, and political complexities that underlie literary maximalism. “Mapping the Maximalist Novel,” in other words, was a great way for students to decide for themselves why readers might “bother” with “big books.”

Q&A with Justin, Harsimran, Kartik, Simrill, and Gabriel

Dr. Alok Amatya: Let’s start with the obvious: what led you to take Dr. Bergholtz’s course “Big Books: Why Bother?” What were your first thoughts when you realized that you were taking a course on “big books” or maximalist novels?

Gabriel Wang: When I was registering for the course, the professor and the topic weren’t finalized yet. So I just signed up for the open slot. Once I realized the course was going to be on maximalist novels, my first reaction was “I’ve made a terrible mistake.”

Harsimran Minhas: When Dr. Bergholtz introduced the topic to us, internally, I was alarmed. I enjoy reading, but these books seemed very complex. But instead of quitting and changing classes, I decided to continue in the course. I took it as a challenge. Even though it would be difficult, I wanted to see if I was capable of reading and analyzing the novels.

Harsimran Minhas: When Dr. Bergholtz introduced the topic to us, internally, I was alarmed. I enjoy reading, but these books seemed very complex. But instead of quitting and changing classes, I decided to continue in the course. I took it as a challenge. Even though it would be difficult, I wanted to see if I was capable of reading and analyzing the novels.

Simrill Smith: Although my answer now is very different, my original answer to the theme would be something like “Big Books: Don’t Bother.”

Dr. Amatya: In Ben’s course, you read Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children and Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings. These two novels are known not only for their length, but for their complexity. How did the process of reading these massive and meandering texts compare with your previous reading experiences?

Justin Coleman: I found reading these books to be a lot like reading a book series. Each individual chapter or part might be straightforward on its own, but to really understand it I had to keep in mind what happened in the other parts and what symbols or characters carried over.

Kartik Sarangmath: Outside of class work, I rarely read literature in my freetime. So for me, reading Midnight’s Children and A Brief History of Seven Killings was like jumping into the deep end of the swimming pool without knowing how to swim. Online resources such as SparkNotes and CliffNotes and in-class discussions helped me very much in understanding the texts.

Simrill : With my most-recent English course focused on poetry, I was used to close reading stanza-by-stanza. When I sat down to read Midnight’s Children, I was met with metaphors and many details about India’s history. I found myself highlighting so much because it seemed like everything was important. The process of reading big books was mentally intensive, it took a while to learn how to read them while managing all my other coursework. Eventually, I found it easiest to look for thematic and figurative trends in the book, and to question weird or mythical occurrences.

Harsimran: Honestly, I thought it was extremely hard to read these books. In high school, my AP English Literature teacher made us read Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky and The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot. However, when we started reading Midnight’s Children, I immediately became confused. Rushdie’s style includes lots of rambling and convoluted sentences that provide too much information. When I read, I usually try to understand every word in the book. This was not possible for me to do with Midnight’s Children. There were so many events happening; it was like an information overload.

Dr. Amatya: After completing a paper and a collaborative presentation on the two texts by Rushdie and James, the class finished the semester with a final project called “Mapping a Maximalist Novel.” Ben, could you briefly walk us through this digital map-based assignment? What did you hope your students would accomplish through it?

Dr. Bergholtz: I suppose my primarily goal was to create an assignment that allowed the students to work through some of the difficulties that Gabe, Kartik, Simrill, Harsimran, and Justin have been describing. I knew that reading maximalist novels would be a challenge, and I wanted to create an assignment that would allow the students, first as individuals and then in groups, to really explore the complexity of the novels with a different set of goals than, say, writing a paper. I also wanted to tap into the students’ creative and technological talents, so a mapping project seemed like an ideal way to engender this engagement.

Dr. Amatya: So there was an individual and group component? What did this look like, in more concrete terms?

Dr. Bergholtz: The assignment included three parts—an individual map, a group map, and a public display. To get things rolling, I brought in some presenters from the Digital Integrative Liberal Arts Center (DILAC) to help familiarize the students with ArcGIS StoryMaps. The learning curve for StoryMaps was a bit steep, so I also allowed students to use other mapping software, such as MapMe and Google My Maps, if they wanted to do so. Regardless of the software they chose, they had about a week to create an individual map analyzing one element of a maximalist novel, the movement of the protagonist, Saleem Sinai, throughout the Indian subcontinent in Midnight’s Children, or of drugs and guns in A Brief History of Seven Killings, for example. The idea was that these maps would not only illustrate something that took place in the novel, but advance an idea or thesis that wouldn’t be possible without the map.

Group work began after I separated the students based on common interests—a student who mapped the role of guns and drugs in Brief History might be placed with two students who mapped the role of the CIA, for example, because these topics are inextricably linked in the novel—and I gave them two weeks to create more dynamic and nuanced maps. During this time, the students considered my feedback, analyzed the merits of their individual maps, and, to my delight, improved their work dramatically by synthesizing the best elements of each student’s work into one (or, occasionally, two) final maps. After two weeks (and Thanksgiving Break), we put on a student expo in The Stephen C. Hall Building with all three classes, and I invited the other Brittain Fellows and people from the university to attend. That event was honestly one of the coolest teaching experiences I’ve ever had. I believe you were kind enough to attend, Alok?

Dr. Amatya: Indeed—it actually helped to generate the interest in this interview on my end.

Dr. Bergholtz: Thanks.

Dr. Amatya: Of course. Turning back to the students, what were your experiences of working on the final project? How did you allocate different tasks within the group for mapping a maximalist novel? How many times did you meet in person or virtually to discuss the assignment progress?

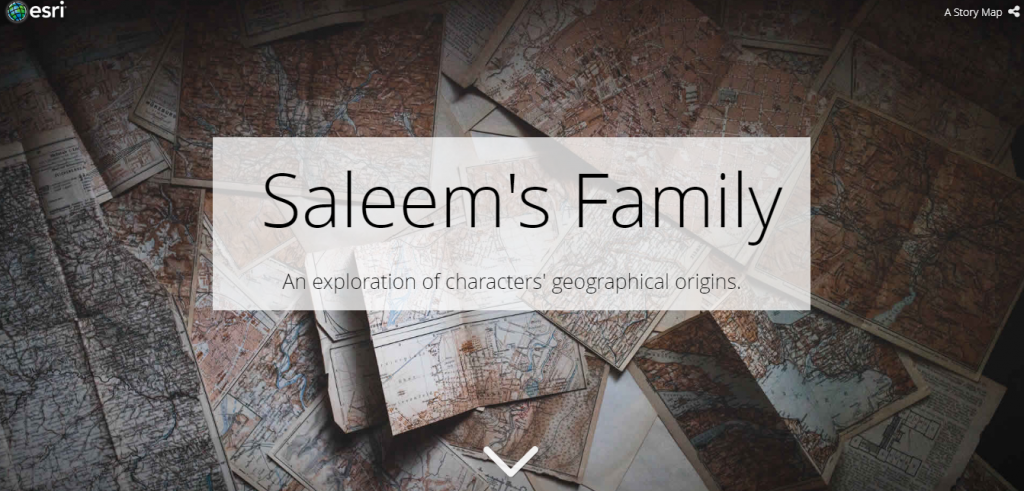

Justin: For my project, I mapped the movement of Saleem’s family in Part 1 of Midnight’s Children. This was clearly a geographical element that related to my understanding of the novel’s characters. I began by finding the locations where Saleem’s family lived, what characters were present there, and what happened to them. From this I created a point on my map for each location, with a picture from the area and a description of how each character was influenced by their time there. Later, in the group stage of the project, I worked with a partner who also mapped Saleem’s family.

Justin’s mapping project of Midnight’s Children is available here.

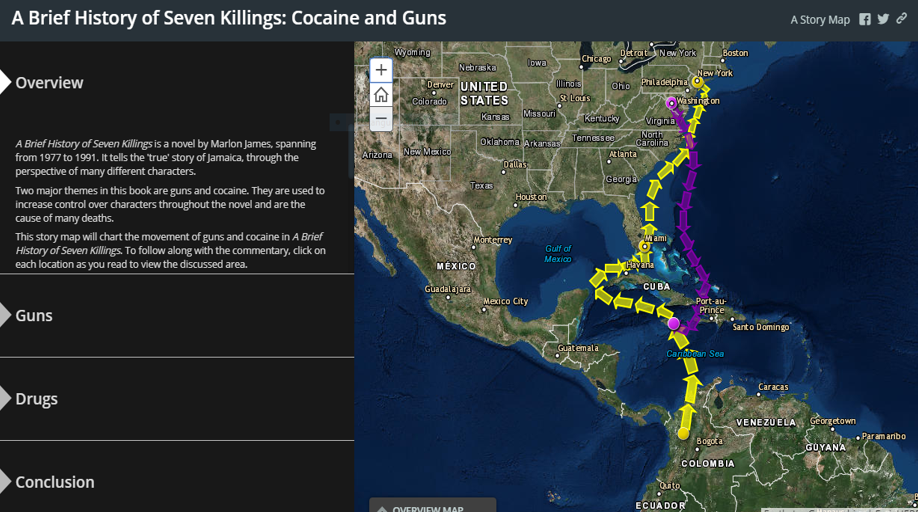

Kartik: Since we had the utmost freedom in this project to create anything we wanted as long as it mapped elements from a “big book,” laying out the structure of our project at the beginning was essential. Because my group members and I were put into groups based on topics we had previously mapped in a project, we all were interested in following guns and drugs throughout A Brief History of Seven Killings. We used class time that we were given at the beginning of the project to layout the general idea of creating two maps, one following the movement of drugs through the novel and the other following the movement of guns through the novel. After that initial discussion, we communicated exclusively through a shared Google Doc and a GroupMe chat. A couple of days before the actual presentation, we worked together to create a structure for the presentation. We did not write out word for word what we would say, but instead we decided the order of who speaks, and how we would tie each aspect of our project together.

Harsimran: When we were first placed into groups, I was a little frustrated. My group members’ topics were similar, but we could not decide how to combine them all into a single map that provided insightful information about the novel. We ended up mapping the movement of drugs and guns in the Brief History of Seven Killings. There were four people in my group. We allocated different tasks on the map based on the strong suits of our individual maps. For example, Tim and I were in charge of formatting the maps, while Lena and Noe mainly analyzed the drugs’ movement. I was also in charge of discussing the movement of guns as I did my individual map on this topic. To communicate with my group members, I created a group chat on the app GroupMe. We also created and shared a Google Doc that included all the text and pictures that would be included in the final map. We met about three times to discuss assignment progress. However, most of the work was done individually at home.

Harsimran’s mapping project of A Brief History of Seven Killings is available here.

Dr. Amatya: Most of students of this course used ArcGIS StoryMaps to complete their final project. How would you describe your experience using StoryMaps, in terms of ease-of-use and the quality of the end product?

Gabriel: Using StoryMaps was fairly intuitive. This online mapping software had a lot of tools that were extremely useful, but were difficult to find. I think that anyone could create a map within a few hours using this software, but someone who is well-versed with its features could make something incredible. I didn’t know about some of the features until my teammates showed me how to use them, and as a result our team presentation was significantly better than my individual one.

Justin: I found StoryMaps to be somewhat difficult to use. Features are not explained very well, it lacks autosaving and other elements I would expect from a modern website, and it has many bugs, most notably an error where it overwrites the text of one location with that of another. That being said, I thought the program was able to create very high-quality maps. They function well, look very polished, and it is easy to interact with and present them.

Kartik: StoryMaps was a great tool to use, but only after figuring out how to use it properly. When I first began to use it, I was quite annoyed at how unintuitive the website was. When one of my classmates showed me a different way to use StoryMaps, however, the different layouts were much easier to use, functioned much better for going from location to location, and looked professional. With the different layout of StoryMaps that I chose, I was able to easily import pictures of locations found on the internet. This helped the user in visualizing the specific location from a person’s viewpoint, while the map view gave the user a better geographical viewpoint. I was also able to highlight areas of land on the map when creating a single point on the map didn’t convey my intentions fully. For example, if I wanted to show where a specific gang operated in a city, highlighting a certain area would be better than having a singular point on the map. Because the locations on my map ranged from Jamaica to the U.S., zooming in and out of the map and panning to different locations was essential for the user.

Dr. Amatya: Turning from the technology itself to your engagement with the big books through it, students, give us a sense of what you mapped? And, what kind of research did you do to on the location and the boundaries of the places you mapped? Was there a rationale connecting the different places you visualized?

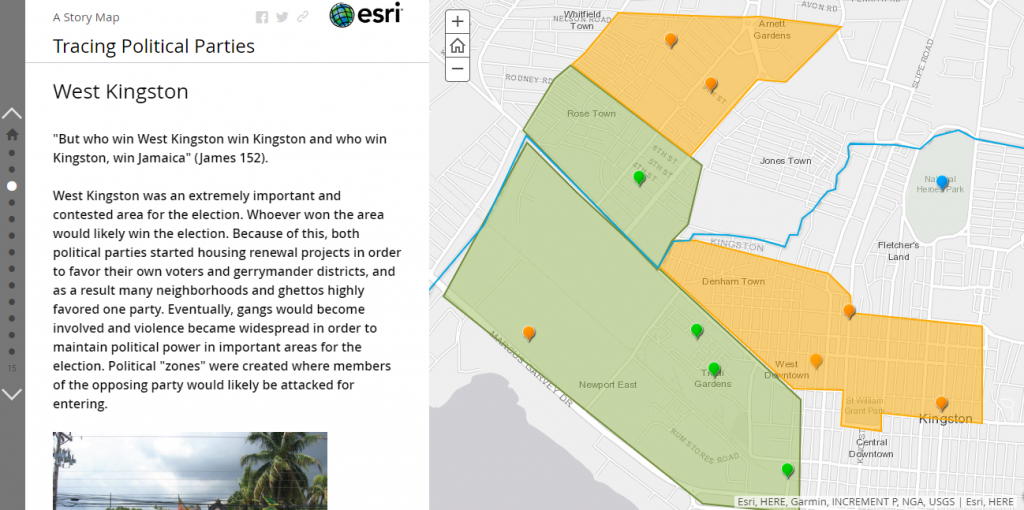

Gabriel: For our map of gangs in A Brief History of Seven Killings, we had roughly 14 locations, and we researched them by looking up online articles, old newspapers, and maps in order to compare them to the novel’s descriptions. It should be noted that the locations we mapped were our estimates, and may not accurately reflect the true political boundaries of the time, but nonetheless we did the best we could and made a compelling product. The rationale connecting the location was similar to an election breakdown, where we would find the areas that were politically affiliated with which part and see where they were located in proximity to other areas of interest. StoryMaps had features that allowed us to highlight or section off certain areas in certain colors which made the distinction very clear.

Gabriel’s mapping project of A Brief History of Seven Killings is available here.

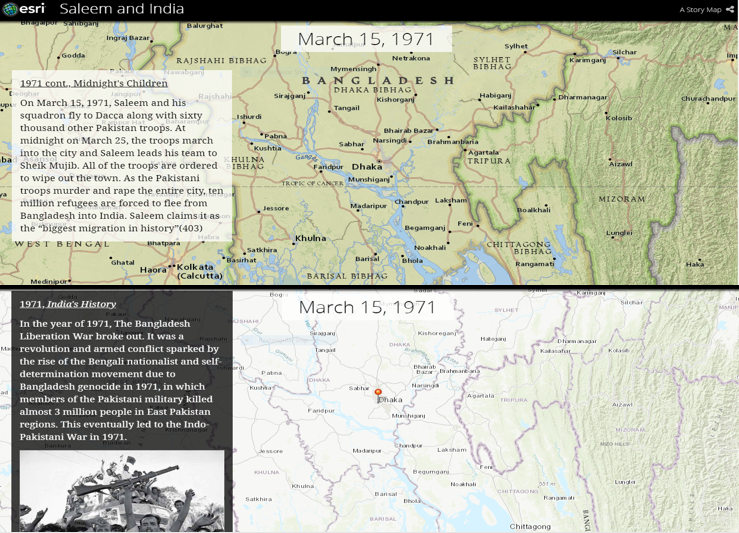

Simrill: We focused on Midnight’s Children. We did some historical research to determine the location of map points, but the book’s events often occurred in non-specific locations. For that issue, we used the event context and cross-referenced it with history to infer a reasonable location. The key visual tool used in our map was the swiping panes effect on the “Cascade” mode. We had two maps—one of India’s history, and one with major events of Midnight’s Children—and as readers scrolled through our project, the panes would switch from one map to the next, changing color. This visual element helped us convey the contrast between historical, somewhat objective facts, and the “facts” of Midnight’s Children. Our map, as a result, was less based on the physical locations themselves, but the comparison from one map to the next. This distinction between history and literature made up our rationale for connecting these various locations; they all were connected to our argument that Midnight’s Children is a work of historical metafiction.

Simrill’s mapping project of Midnight’s Children is available here.

Dr. Amatya: What do you think of digital mapping as a means of interpreting “big books”? In what ways did you feel intellectually challenged by undertaking the final project? What was the payoff from this mapping assignment?

Gabriel: I think digital mapping was a fantastic way of interpreting big books, because of the difficulty in following them. After mapping out the locations, I found more of the actions understandable and was able to connect multiple characters’ perspectives, something I wouldn’t have been able to do if I were just reading the text alone. Of course it was still challenging, as there were no true set boundaries for certain areas, many of the locations were estimates based off novel details and historical evidence. But I better understood the history of the setting and the novel as a result.

Kartik: Mapping out the novel geographically helped me understand the novel better, because while reading the book, I was not familiar with the locations and references mentioned. After mapping out the locations, I was able to better picture many of the events that occurred in A Brief History of Seven Killings. For example, I knew that Kingston is a city in Jamaica, but that was all. After mapping many events from the book that took place in Jamaica and researching them, it was much easier to picture what was happening in the book. I found out what West Kingston looked like, I found out what the penitentiary looked like, and I could better relate with the characters after seeing from their viewpoints. I would say that the most challenging thing for me was relating the locations I mapped to the narrative I was telling. I couldn’t just write my narrative as though it was separate from my map. The two were supposed to help each other, and thinking about the significance of the locations and how it was connected the analysis of the book was challenging.

Kartik’s mapping project of A Brief History of Seven Killings is available here.

Justin: “Big books” of this sort have complex structures involving many characters, symbols, and locations. I think mapping them provides an excellent means to visualize this complexity and investigate how the different parts of the novel are connected.

Dr. Amatya: How were your experiences in undertaking a multimodal assignment of this sort different than, say, writing a text-based research paper on the same topic? Did you perceive different learning outcome at the end of the course?

Kartik: I believe that I learned more about the book and the historical events in the book by doing this multimodal assignment rather than an essay. Writing an essay usually is a linear process where I have a prompt that I have to answer. The mapping project allowed me to think more about the historical context of the book, as well as think more about the geographical settings in the book. And since there was freedom to pick pretty much any topic in the book to map, I mapped a topic that I was actually interested in.

Harsimran: Yes, I felt that doing the multimodal activity was more beneficial than writing an essay. I believe that the multimodal assignment required much more understanding and analysis of the novel than an essay would.

Justin: I felt that this assignment allowed a better analysis of the novel than an essay would. Where a college paper typically takes on a relatively narrow topic or viewpoint and has a prescribed structure, this assignment focused on the novel more generally, requiring us to consider many different locations within it, and allowed much more freedom of format. This made the assignment feel much more hands on and, in my opinion, allowed me to understand the novel more deeply than if I had written another paper. In addition, I think that by making use of an unfamiliar program and requiring a public presentation, this project gave me experience that will be more useful to my other classes than a paper would have been.

Simrill: The multimodal nature of this project was beneficial in some ways beyond a traditional college paper. My first project, the annotated essay, included some of the same themes of historical metafiction that I explored in the third project. Although the essay was still an effective way for me to find meaning in the novel, the map had the payoff of adding visuals and movement to my argument. Both projects involved a similar process of analysis to complete, but the map was a more-dynamic way for me to convey what I had found.

Dr. Amatya: As you reflect back on the semester as a whole, what were some of the things that you liked about the way your were engaged by the final project? Which aspects of it did you find rewarding?

Gabe: I liked how much my choices would affect the final product. Not only would my individual topic be allowed to shine, but it could be improved on vastly through the help of my teammates and peers. Unlike the other projects, which were either purely individual or purely team-based, this project was a healthy mix of both.

Justin: I liked being able to choose my own topic for the assignment; I found it rewarding to pursue my own interest in the novel and build up a web of locations from that interest. I felt this was complemented by the gradual widening of topics in the other assignments, moving from a choice of three in assignment one to anything within a section in assignment two to any topic in assignment three.

Harsimran: My favorite aspect of this project was how open it was; students could choose their own topic and the way they mapped it out. This allowed me to complement my topic with my questions about historical ambiguity raised in my first project. This ordering was also good because it combined several of the elements I learned. In project one, I learned how to synthesize an argument from a huge piece of literature, and in project two, I practiced working with a group to close read a specific chapter. The group map involved both group-intensive work and developing a thesis on an entire meganovel topic. Additionally, the final expo was especially cool because I was able to meet other students while learning from their specific maps.

Pedagogical Reflection

When I designed “Big Books: Why Bother?,” I was excited about the chance to teach maximalist novels, but also a little apprehensive about how I would be teaching them. As an incoming Brittain Fellow, my experience with multimodal pedagogy was limited—I had certainly never taught anything like digital mapping—and I worried that my multimodal assignments would distract from my students’ analyses of maximalist fiction rather than enhance them. Reflecting upon my students’ commentary, I see that the opposite was true. Asking my students to digitally map maximalist novels did not interfere with their engagement with these complicated texts, but it helped them to understand and appreciate their complexity.

There were trade-offs, of course. We only read two novels, they only wrote one formal paper, and devoting time to digital mapping necessarily meant our class had less time for large group discussions than one would find in a traditional literature course. But these trade-offs proved beneficial. Focusing on only two novels allowed the students to process what they were reading, and mixing in multiple forms of writing— informal in-class writing, a digital discussion board, and their “Story Maps”—helped them to become savvy multimodal communicators. As Justin put it, splitting time between discussions and mapping was an “excellent means to visualize the complexity [of maximalist novels] and investigate how the different parts of the novel[s] are connected.” Digital literary mapping, in short, did not occlude my students’ ability to consider the question at the heart of the class—”Big Books: Why Bother?”—instead, it helped them to answer it on their own terms.