Before introducing any new strategy in the classroom, whether it involves technology or not, I think we must always ask ourselves: what is the pedagogical imperative? After all, just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we should. So, I’ll start by trying to answer the question: what can multimedia resources, particularly digital or new media, provide that texts alone cannot?

Why use multimedia in the medieval literature classroom?

One answer stems from my belief that any introduction to medieval texts should include an introduction to medieval studies as a discipline, one that has long since entered the digital age. One of the highlights at this year’s International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo was the revelation of the identity of the Chaucer blogger, Brantley Bryant, whose Medieval Studies and New Media was released this year by Palgrave Macmillan. During July’s biennial meeting of the New Chaucer Society, Stephanie Trigg organized a session on medievalist blogging (Jeffrey J. Cohen offers a session redux on In the Middle, a self-proclaimed “medieval studies group blog”). On Thursday, August 5, the fan base for the Medievalists.net Facebook page surpassed 7,000 users. Increasingly, the web houses important new media tools for medieval scholarship, such as the Middle English Compendium, and pedagogy, such as the invaluable TEAMS digital editions produced by the Medieval Institute. Medieval scholarship has become a multimedia affair, and students should be familiar with how it has evolved with the assistance of and in response to digital and new media.

One answer stems from my belief that any introduction to medieval texts should include an introduction to medieval studies as a discipline, one that has long since entered the digital age. One of the highlights at this year’s International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo was the revelation of the identity of the Chaucer blogger, Brantley Bryant, whose Medieval Studies and New Media was released this year by Palgrave Macmillan. During July’s biennial meeting of the New Chaucer Society, Stephanie Trigg organized a session on medievalist blogging (Jeffrey J. Cohen offers a session redux on In the Middle, a self-proclaimed “medieval studies group blog”). On Thursday, August 5, the fan base for the Medievalists.net Facebook page surpassed 7,000 users. Increasingly, the web houses important new media tools for medieval scholarship, such as the Middle English Compendium, and pedagogy, such as the invaluable TEAMS digital editions produced by the Medieval Institute. Medieval scholarship has become a multimedia affair, and students should be familiar with how it has evolved with the assistance of and in response to digital and new media.

The second answer arises out of my desire to bring pre-modern texts alive for my students by immersing them, both the texts and the students, in rich historical context. Increasingly, we can access that historical context online via digital images and archives, and other web-enabled technologies. Further, we should not forget that medieval culture itself embraced a variety of modes and media. In an age with multiple definitions of literacy, visual art, architecture, and drama provided important alternative media outlets for transmitting ideas and texts religious and profane. Exploring how that process continues via the world-wide-web, documentary photography and videography, film and television adaptations, and even the medievalism of immersive gaming gives us insight regarding the life and afterlife of medieval texts. Studying the “multimedia, multimodal Middle Ages” can help students come to terms with those texts, which can, let’s face it, be intimidating in their historical and aesthetic estrangement from the modern.

Using multimedia texts as secondary sources — the lower-division classroom

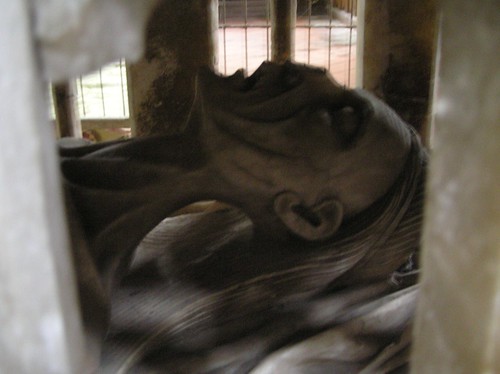

So now that we have covered the “why,” let’s turn to the “how.” One can, of course, integrate multimedia resources as secondary material to supplement the primary text. This approach works particularly well in composition and lower-division survey classes. As part of a unit on Chaucer, for example, I might have my students do some research on Flickr, running keyword searches for terms such as “Canterbury Tales,” “Ellesmere Chaucer,” “Canterbury Cathedral,” “Thomas Becket,” “relic,” and “pilgrimage.” Then, in class, we would pull up some of the found images on screen for discussion along with textual passages to which they are relevant.

So now that we have covered the “why,” let’s turn to the “how.” One can, of course, integrate multimedia resources as secondary material to supplement the primary text. This approach works particularly well in composition and lower-division survey classes. As part of a unit on Chaucer, for example, I might have my students do some research on Flickr, running keyword searches for terms such as “Canterbury Tales,” “Ellesmere Chaucer,” “Canterbury Cathedral,” “Thomas Becket,” “relic,” and “pilgrimage.” Then, in class, we would pull up some of the found images on screen for discussion along with textual passages to which they are relevant.

We might also use Google Earth to take a virtual tour of Canterbury Cathedral, and to plot the route Chaucer’s pilgrims might have followed in their literary journey. Exercises like these help students understand that the text, an act of imaginative generation, nevertheless had a connection to a real historical context. More than six hundred years later, the historical context endures in fragments, like the text itself, that have been incorporated into our modern cultural environment. Medieval literature, like medieval architecture, is “of the past,” but it is also part of the present, a part that we have taken pains to preserve. The conversation about why we have preserved it, and what medieval texts and artifacts have become versus what they may once have been can provide a point of access for close reading and analysis that moves students beyond plot and character summary.

Using multimedia texts as primary sources — the upper-division classroom

For more advanced students, multimedia resources can be essential tools in an introduction to textual scholarship. Very few of us are lucky enough to work at schools with ready access to manuscript archives. Fortunately, a number of projects are working to make original texts available in digital form. One of the best is the Auchinleck Manuscript site maintained and hosted by the National Library of Scotland. The site provides full-text searchable transcriptions of the manuscript text, a digital facsimile of the entire MS, as well as excellent background information on the manuscript and a comprehensive bibliography of scholarship dealing with the MS as material artifact and as text. Beginning Middle English paleographers can use the digital facsimiles for exercises in transcription and basic recognition of different “hands” or writing styles. They can find an excellent overview of textual studies and late-medieval manuscript culture in the bibliographic material. The lacunae left in the manuscript by the vandals who raided it for miniatures are poignant and telling reminders of the significant differences between manuscripts handcrafted from vellum, ink, and gold leaf, and digital texts comprised of computer code and created with machine assistance. Thus, as a convergence point between the digital/postmodern and the manuscript/medieval in the history of the book, the site itself can become an important object of study.

For more advanced students, multimedia resources can be essential tools in an introduction to textual scholarship. Very few of us are lucky enough to work at schools with ready access to manuscript archives. Fortunately, a number of projects are working to make original texts available in digital form. One of the best is the Auchinleck Manuscript site maintained and hosted by the National Library of Scotland. The site provides full-text searchable transcriptions of the manuscript text, a digital facsimile of the entire MS, as well as excellent background information on the manuscript and a comprehensive bibliography of scholarship dealing with the MS as material artifact and as text. Beginning Middle English paleographers can use the digital facsimiles for exercises in transcription and basic recognition of different “hands” or writing styles. They can find an excellent overview of textual studies and late-medieval manuscript culture in the bibliographic material. The lacunae left in the manuscript by the vandals who raided it for miniatures are poignant and telling reminders of the significant differences between manuscripts handcrafted from vellum, ink, and gold leaf, and digital texts comprised of computer code and created with machine assistance. Thus, as a convergence point between the digital/postmodern and the manuscript/medieval in the history of the book, the site itself can become an important object of study.

Multimedia and multimodal assignment design

Finally, in addition to studying multimedia primary and secondary sources, one can take a multimedia approach to assignment design. During the Spring, I taught a first-year composition class where we studied adaptation, transformation, and appropriation as creative performance. In that class we looked at how adaptation can in some cases work as a kind of interpretive scholarship. Our discussions of The Canterbury Tales framed Chaucer’s text as an adaptation of his source material. We studied stage and television adaptations of The Canterbury Tales, and then I designed a progressive assignment sequence in which the students created and reflected upon their own adaptations of Chaucer’s work. Along similar lines, Cynthia Camp, allowed her upper-division students at the University of Georgia to create a “Choose Your Own Chaucer” videography project, adapting Chaucer’s “Legend of Dido” from the Legend of Good Women for the small screen. In undergraduate classes such projects can be a welcome relief, for both teachers and students, from formulaic essay assignments in which many students resort to reproducing well-worn arguments about “what Chaucer was really thinking.”