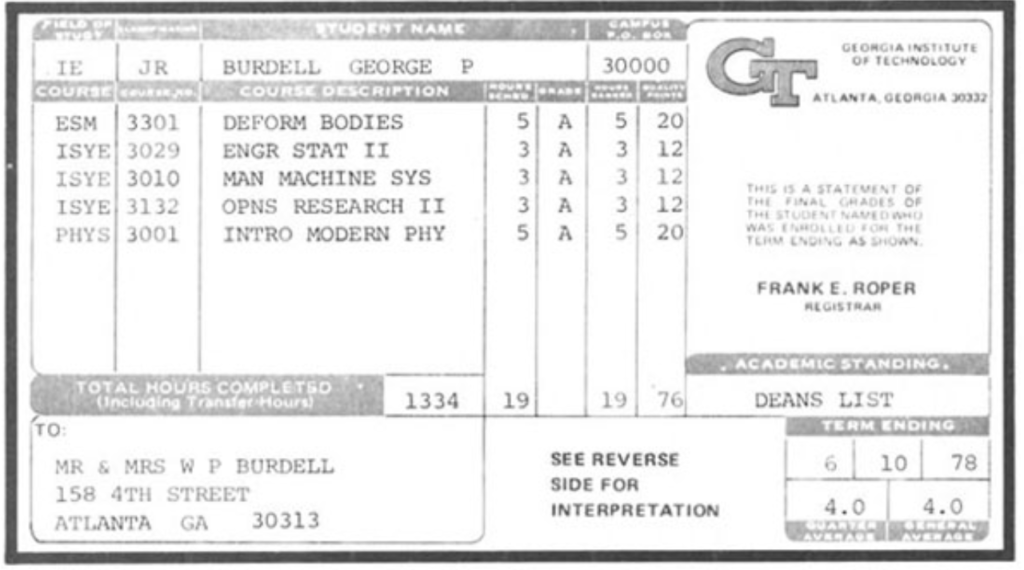

George P. Burdell’s report card, 1978.

As a teacher, I crave autonomy. I want to produce material that reflects my persona, my research background and interests, and my learning objectives. I admit I have difficulty delivering lesson plans and assignments I did not create. No doubt a teacher’s attitudes show, and students perceive enough, I believe, to sense on them. The question is: If I treat an assignment like it is something to survive, will anyone enjoy it? Sometimes, probably, but in my experience an instructor’s opinions and attitudes can be contagious, particularly catching among students who connect strongly with that instructor. For example, when I was an undergraduate student, I had a professor of medieval studies, who believed as a few of them do, I hear, that there has not been a single quality thing published since the Middle Ages. That opinion so infected me that I carried my disdain for Hemingway and Hawthorne like a rash for a few years, and it was not until I became an M.A. student that I was able to cure myself of it. In short, I would argue that our students pick up on much that is said and unsaid.

The purpose in writing this article is to discuss a realization I had regarding potentially negative effects my attitude toward a specific programmatic assignment, the Common First Week video project might be having on my students. It took time, but I finally came to understand that by thinking creatively, I could be faithful to the assignment description and still make the assignment unique to my class, while simultaneously giving my students license to be creative themselves by engaging with the lore of a particularly famous campus legend: George P. Burdell.

The Common First Week Video

Common First Week Video Assignment Description, Writing and Communication Program, Fall 2020.

Every semester in English 1101/1102 courses at Georgia Tech, the first artifact students complete is a programmatically standardized assignment with many names—the Common First Week video (also known as the Multimodal Reflective Video Assignment or Artifact 0). The basic elements of the video should include the following:

- The video must be between 60-90 seconds.

- Students will use narrative strategies to support their claims, which articulate a challenge relating to one of the modes they expect to encounter in the course and potential goals for overcoming that challenge.

The purpose of the assignment is to give the students a low-stakes task introducing them to the multimodal framework that shapes English Composition courses at Georgia Tech. It also provides the instructor with an idea of where student proficiency lies relative to multimodal composing and critical thinking. Because it is standardized across all English 1101/1102 courses, a student can drop one English Composition course and add one taught by a different instructor and still expect to do the same assignment, thus preventing those students from falling behind, at least at the outset of the course.

While I appreciated that the standardizing of this assignment could benefit students in multiple ways, I initially felt that the program was 1) reducing my agency in the classroom through micro-management and 2) potentially hijacking my students’ first impression of the course rather than giving me the freedom to set the tone for the semester. Why hire such a diverse group of talented PhDs with wide-ranging interests only to immediately limit us in what we can do? To be fair, there are many other programmatic arguments for this assignment, which I do not have the space to engage with here. All I can say these are concerns and questions I had when I first began to teach here. As, no doubt, many of us feel, I am certain, I am not a expert at acting as though fully committed to something when I am not actually committed, and I do not have a poker face. From what I could tell, many of my students were as begrudging about creating the CFW video as I was in assigning it. While it could have been in part because the assignment introduced them to a realm of composing outside of their comfort zone—though so many of them dislike the written mode so intensely because of years of five-paragraph essays and bombed AP exams, one would think more of them would be going ape over a non-traditional composition assignment like this one—I believe that my own poor attitude also played a role in their lack of eagerness.

It took me a year at Georgia Tech to realize that I was probably part of the problem. I needed to stop focusing on the pre-prepared ingredients of the assignment and start focusing on a recipe that could make this assignment more interesting to me so that I was not becoming an impediment to my students’ learning. In short, I needed to find at least a small way in which I could make the assignment my own. So I did. And it changed my attitude. I also started to see better CFW videos, and the excitement levels in the classroom seemed to rise, though perhaps it only seemed that way because I was more satisfied. Either way, I owe my improved experience with the CFW video to George P. Burdell, as well as to numerous students who accepted the lack of orthodoxy and embraced the madness.

George P. Burdell: A Campus Legend

Nearly every freshman, at some time before they come to my class, hears the story of George P. Burdell, a fictitious student invented by a William Edgar Smith during the 1920s. Burdell, the legends say, has taken every class at Georgia Tech on his way to becoming a celebrated, subversive campus legend whose accolades, according to his Georgia Tech web page and Wikipedia, include advanced degrees and military service. As recently as October 2019, a stolen plaque was returned to Georgia Tech by a man in his 60s who would only give the name of George Burdell.

Part of my research background is in folklore studies, and I have long been interested in the scholarly work of celebrated folklorist Libby Tucker, author of Campus Legends (2005) and Haunted Halls (2009). According to her, these legends provide one of many traditional ways for students to connect with and even reenact campus tradition and history and create community. Engaging with and sharing these legends can provide students with an outlet for expression that allows them to entertain and teach each other, as well as either transgressing or maintaining cultural norms.

Many university campuses are hotbeds of folklore, and though I had never heard a campus legend quite like this one, I saw in the Burdell stories many of the same characteristics and functions exhibited by other campus legends, particularly in the way the story upholds institutional values (e.g. exceptionalism and intelligence), while also subverting those same values through trickery and deception. Since the beginning, Burdell has functioned as the performed embodiment of existing within rigid institutional frameworks and finding creative ways to circumvent them. (For example, Georgia Tech might pride itself on rigor, yet somehow from 1927–1930 William Smith and his friends undermined that institutional value by managing to take classes as Burdell without the university’s knowledge and turn in all of Burdell’s homework and assignments in addition to their own.) Upon learning about Burdell and finding examples of how the legend has endured and evolved for nearly a century, I wanted to give my students a chance to engage with the legend in my course. Ultimately, I asked myself, What would George P. Burdell’s CFW video look like if he were in my English course?

Implementing the Assignment

As part of the process of helping students wrap their brains around the assignment, I began to task groups of them with writing “The Lost Video Script of George P. Burdell.” In my mind, the mini-assignment would help them practice applying the guidelines of the CFW video as they produced humorous scripts from Burdell’s perspective. I also hoped it would reinforce the need to approach the CFW video—and other assignments in my class—with creativity and charisma, rather than simply going through the motions and meeting basic expectations.

For this activity, I break the students into groups of 3–4 and provide each group with a worksheet with three headings:

- Introduction (“Hi, my name is George P. Burdell, and I am enrolled in Dr. Howard’s English 1101 course…” etc.)

- Challenge (related to one of the modes of communication we discuss in the course)

- Goals (strategies for overcoming the challenge)

From my perspective, the students generally enjoy connecting the goals of the assignment with the Burdell legend. The groups integrate with their script some of Burdell’s legendary “accomplishments” (gleaned from online sources such as Georgia Tech’s alumni pages and Wikipedia), such as Burdell’s candidacy for Time’s Person of the Year award or the fact that his name was engraved on a satellite. They also take full advantage of his folkloric status and liberally create new aspects of Burdell’s personality that innovate on known narratives, including Burdell’s stuttering or his helplessness when navigating new technologies that did not exist in the 1920s.

After drafting a quick script, each group selects one of its members to read it for the class. We laugh and clap as each speaker reads their script and embodies the Burdell persona. Some readers are serious, but most of the students read with whimsy as they make jokes about how Burdell seeks to develop his communication skills so he can present himself as an actual person, how he struggles with presentations because no one can actually see him, or how his difficulties with nonverbal communication have impeded his ability to attend classes and have led to widespread doubts about his existence. The amount of engagement and creativity the students demonstrate during this in-class activity transforms how we approach their videos and gives them license to try new things rather than simply grin and bear the assignment, as I had done in teaching it.

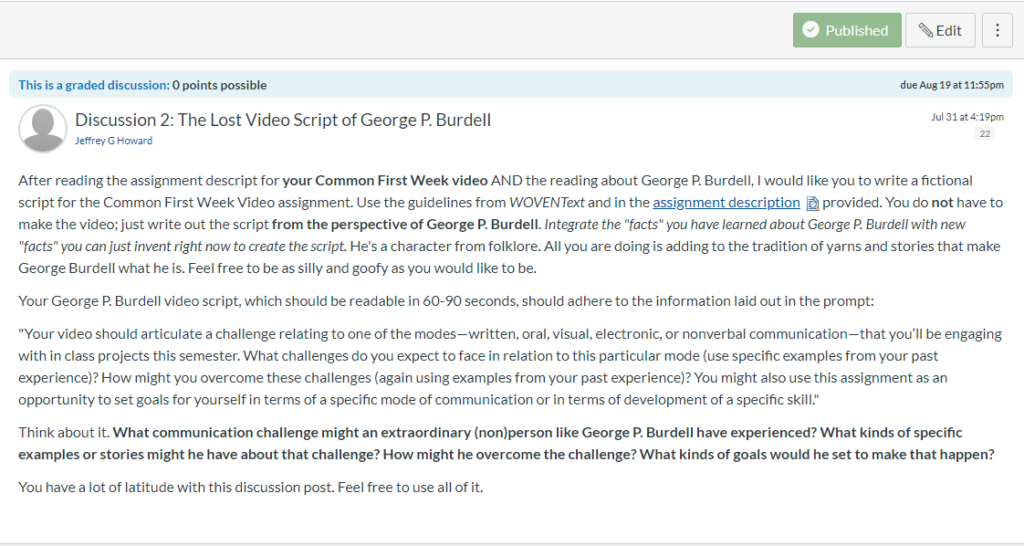

Prompt for Burdell Assignment, Fall 2020.

When the COVID-19 pandemic occurred and I prepared to teach in a hybrid format, I made the decision to teach primarily asynchronously, but I wanted to preserve much of my content, including this assignment. Instead of holding BlueJeans meetings with breakout rooms as some of my colleagues do, I chose to use Canvas discussions for student responses to readings. During the first week, I assigned two discussion posts: the first asked for a short video in which students introduced themselves and the second asked students to individually create the Lost Video Script of George P. Burdell. In the past, when I made it an in-class collaborative group activity, students discussed the prompt and source material, thus benefiting from each other’s ideas. At the same time, because it happened in class, they had the pressure of trying to produce a Burdell video script in less than 15 minutes. In our asynchronous learning environment, I modified it to be a low-stakes, individual assignment with which students had complete creative control; they could be as conservative as they wanted to be or go wild. Additionally, each one could compose at their own pace (though I still did have a deadline).

In the online version of this assignment, some students wrote very simple scripts, which I expected. This discussion post, which is one of twenty they do for the semester, is not worth very much in the grand scheme of things, and they receive participation credit for just showing a good-faith effort with the assignment. If they want to overachieve, it is 1) because of who they are, 2) because they are trying to impress me, or 3) because they are having fun.

Outcomes

Those who had fun with it produced some very comical and ambitious scripts in just a short time (and some might have gone a little overboard on writing out stage directions, musical scoring choices, and scenery description, none of which I had explicitly asked for). Multiple scripts had much more stage direction than one usually sees in a Common First Week Video script. One script narrates, “*Burdell produces a piece of paper and proceeds to read the most beautiful poem ever to touch human ears. Women faint and men cry and the audience as a whole falls tragically in love with Burdell, unable to handle this electric combination of smooth jazz and poetry.*” Burdell then says confidently into the camera, “That’s nice, isn’t it?”

Once again, students read the source material and quickly realize that there is little or nothing that Burdell cannot do or become, which is, of course, one of his traditional functions as a folk-hero on a campus that pride itself on innovation. The students are not limited by lore, either; rather the lore gives them license to invent and explore, and in the end they bring together folklore that existed before them and new stories they invent themselves. They write things like the following excerpts:

Student 1: “I have done a lot over the years ranging from serving as a B-17 pilot in WW2 to hacking UGA’s calendar in 2014 to post an event saying “Get [Ass] Kicked by GT.”

Student 2: “Throughout my life, I have excelled in many different forms of communication through my time on the Board of Directors at MAD, my global travels as a basketball player, and my work repairing airplanes for the United States Air Force. I love getting involved locally, especially on campus, attending every event that I possibly can.”

Like everyone else, however, Burdell still has his struggles with communication.

Student 1: “However, I still have much to learn at Tech, especially pertaining to nonverbal communication. The reason that I have always had trouble with this mode is simple; I have no physical body.”

Student 3: “Things like visual and oral communication have never come naturally. You see, I value my privacy very much. Even though I’m a bit of a local celebrity I don’t like for people to know what I look like or know much about me at all. It’s actually become kind of a problem. I’m a very diligent student normally. I think at this point I’ve earned every credit there is on this campus, I’ll turn in every homework assignment or essay on time, but I’ll always be conveniently missing on days where I might have to present something or show my face in class.”

Student 4: “In this new age of the Internet I find that I have a hard time communicating via digital platforms. To put it short, my TikTok page sucks and I don’t know how to use Facebook. I’ve just spent so much time earning Georgia Tech degrees, teaching Elon aerospace engineering, single-handedly solving various global issues, and saving puppies from burning buildings that I’ve just completely neglected the electronic mode of communication. Also did I mention that I started training for the Olympics recently?”

And like all of us, George has certainly been affected by the pandemic, as one script notes: “You do not want to know how lonely I’ve been in quarantine.” In this instance, George served as a mouthpiece for feelings that a single author happens to share with numerous other people across campus and throughout the world. Many of these students exceeded my expectations with what was supposed to be a “process document,” a means to help them understand the “real” assignment that they would need to turn in the following week, but I believe that for many of them inhabiting the persona of Burdell gave them an outlet for pent-up creative energy. One student even made her script into a video (which I include here by permission) in which she performs the role of George P. Burdell.

Conclusion

Ultimately, both of my approaches to this mini-assignment have had their advantages. The Burdell legend represents a collective/community narrative effort, both in the legend’s creation (Smith and friends, for example) as well as in the way the legend has evolved and grown over the years (the way all folklore does) through different people adding their yarns to the body of Burdell narratives. Thus, it is appropriate to make this assignment a group project as well. At the same time, I enjoyed seeing what the students produced within the guidelines I provided because each script then became a glimpse at each student’s individual flair or style for story-telling. Legends are a space to articulate both collectivism and individuality, and the ways I have presented this assignment to my students can emphasize either one. I am content that in our online class it was an individual assignment because it meant that students spent more time crafting and polishing their script than navigating new technologies and collaborative strategies while trying to pass the draft among their group members. Once again, either of those are commendable objectives, but for what I wanted to accomplish at this point in the semester, I preferred to give them more time to invent on their own.

One additional key takeaway from this experience for me has to do with the fact that all of us exist within a set of constraints. I am not sure there is a point in being sour about them; constraints are a fact of existence. No institution is obligated to provide its members with absolute freedom, no matter what they want. At the same time, my students—and perhaps even George P. Burdell—have helped me understand that constraints can also facilitate creativity. When you build a dam, the water still has to go somewhere; that is true also within the context of teaching and learning. The CFW video did not originate with me, but it became mine and my students’ as we exerted our creative capacities within the given framework and produced something that connected us to a bigger, broader sense of “us,” a particularly timely benefit given the isolating constraints that society and the global health crisis have placed upon each of us.