During the pandemic, university instructors, staff, and students have faced numerous challenges within the context of higher education, and mental health and wellbeing have emerged as key issues in discussions relating to equitable student support and classroom learning. We asked Brittain Fellows to share their experiences with making student mental health and wellbeing focal points in their pedagogical practice. We hope you enjoy the following contributions by Wendy Truran and Leah Misemer in response to our call.

“Researching Resilience: Student-Led Strategies for Cultivating Academic Resilience” by Wendy Truran

Resilience: “The capacities for persistence, adaptation, emotional intelligence, cognitive flexibility, creativity, and recovering from adversity.” This is one of the definitions of resilience that my students and I collaboratively created. In the semester that COVID-19 hit us, I designed and taught a course called, “Writing, Reading, and Resilience.” In addition to meeting the learning objectives of ENGL 1101, my goal for the class was to present strategies, science, and stories that might offer students different ways to think about mental-emotional wellbeing and cultivate academic resilience.

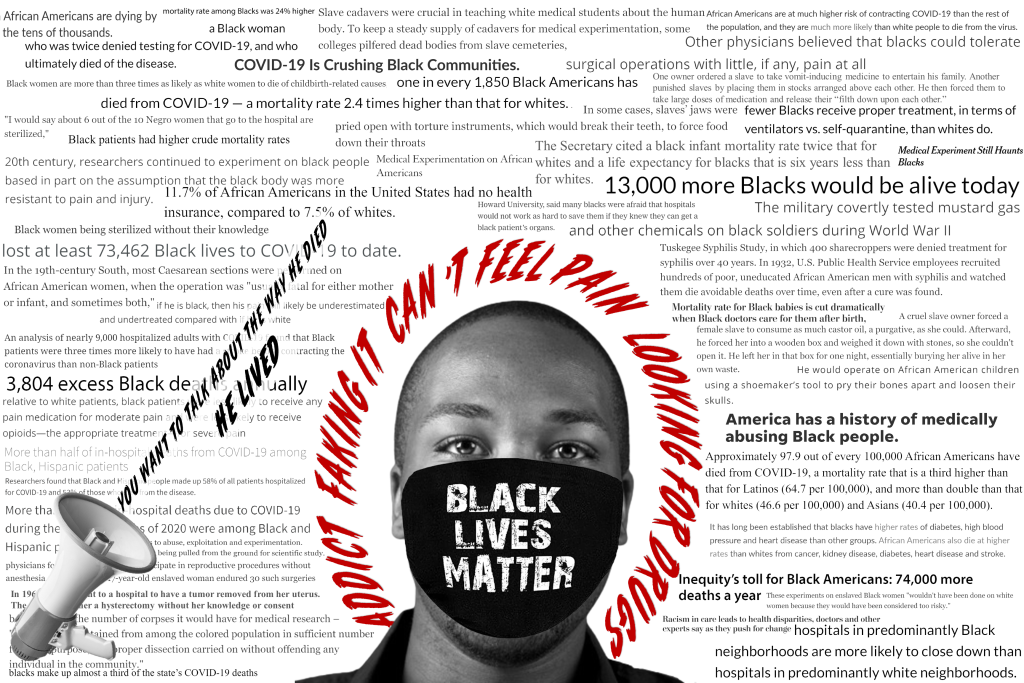

Figure 1: Top concerns of students visiting the Georgia Tech Counseling Center. These align with national data trends from the AUCCCD and with national data from the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS), a multidimensional assessment and outcome measuring instrument utilized by the Georgia Tech Counseling Center. Figure taken from “A Path Forward – Together Student Mental Health at Georgia Tech”, November 1, 2017. A Path Forward — Together: Health and Well-being (gatech.edu)

I started from a very simple premise, that we need to talk about mental-emotional health better and more. Furthermore, to hear the stories of others, to find rich language for our feelings and thoughts, and to know “you are not alone” can make a positive difference to mental wellbeing.

I modelled ways to talk about the mental-emotional difficulties of everyday life through the analysis and discussion of oral histories, literature, poetry, academic articles, and art. This offered students a vocabulary for, and normalized talking about, mental-emotional health. [1]

Two of the multimodal assignments that I designed helped students articulate the problems that impact them and discover approaches for addressing them. The assignments, a research poster presentation and a digital toolkit, guided students to identify an issue that negatively impacts college students and then find scholarship defining the problem and the solution. These two assignments, discussed in detail below, combined self-reflection, analysis, research strategies, and communication competencies in written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal communication (WOVEN) modes.

In researching a topic touching on mental-emotional health, students became more comfortable with talking about the topic. They developed a vocabulary through which they could consider the intersectional issues that impact mental-emotional wellbeing. In finding and communicating their chosen topic, they more fully understood the scope of the issue and how people were approaching the problem (thereby understanding they were not alone in their concern).

Defining the Problem: A Poster Presentation

By allowing students to identify a topic that impacted their lives directly, or lives of their peers, it emphasized the exigence and everydayness of the issues, underlining the fact they are not alone in their concerns.

Figure 2: Student research poster discussing the challenges of succeeding as a female international student in a STEM discipline.

A short list of the topics that students researched:

- Dropout Rates and Retention for Minority Students in College

- First-Generation Student Experiences

- Imposter Syndrome

- How to Succeed as an International Woman in Engineering

- Perfectionism and its Long-Term Effects on College Students

- Student Debt

- How to Retain Female Students in STEM programs

- Procrastination and Its Impact on Academic Success

- Problems with Sleep and Its Impact on Wellbeing

- Social Media and Its Effect on Mental Health & Self-Esteem

- Food Insecurity on College Campuses

Public speaking is a source of anxiety for most people, and a conference-style presentation increases the number of times you articulate your research and lessens the presentation anxiety. The research and poster presentation sets up the student to be the most informed person on the topic, and the experience can increase self-confidence and reduce feelings of imposter-syndrome about presenting. In addition, by focusing on the iterative process of drafting and translation, it encourages students to develop a growth mindset which is also beneficial for academic resilience.

Finding Solutions: An A-Z Toolkit for Resilience

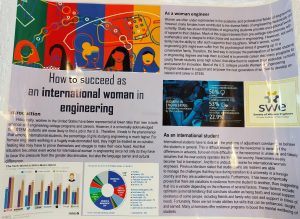

While the research poster focused on problems, the “A-Z Toolkit for Resilience Strategies” emphasized approaches for addressing the issues raised or read about in class. A toolkit is a student-generated resource that explores the habits, attitudes, actions, skills, and capabilities that can increase resilience. Drawing on scholarly research, each student identified a tool for building resilience and communicated the guidance via a multimodal blog.

Seeking to create a resource within, and potentially beyond the class to the wider student body, the students produced an electronic multimodal resilience toolkit. The aim of the toolkit was to provide a resource for and by students to promote persistence, passion, adaptation, creativity, and cognitive flexibility for use at a university.

Figure 3: Student research on a tool for resilience.

Each student identified one tool for building resilience and conducted research into how it might increase resilience for their peers.

Students wrote about the tools of resilience such as:

- Acceptance

- Cultural Identity and Community

- Creativity and Crafting

- Exercise

- Family & Friendships

- Laughter

- Music

- Mindfulness

- Positive Reframing

- Sleep

- Sports as Community

- Self-Compassion

“I Thought It Was Just Me”

I heard the phrase “I thought it was just me” or “huh, I never thought of it that way” a lot during the semester. The readings and research in the class sought to communicate that it is never “just you” (whatever ‘it’ is, it’s usually systemic and often incredibly common). Yet if we don’t talk about mental-emotional wellbeing as part of our everyday experience, then it can feel that way – silence and secrecy fuel shame and isolation. By focusing on the crises of everyday life, offering diverse examples of ordinary people being resilient, and asking students to be active in the research of their concerns, it presents another strategy for cultivating resilience.

“Making Space: Supporting Student Empathy” by Leah Misemer

Like my colleagues from the anti-racist pedagogy post, after the global protest summer of 2020, I felt like I was being called felt to help students think about race in America, and particularly about the Black experience. Spurred by previous semesters of students asking how to converse across the multitude of national divides, I focused my class on how different media generate a skill that humanists often identify as the most valuable in our disciplines: empathy. Psychologist Jamil Zaki’s research shows that empathy is a skill that can be taught, and numerous business leaders, including the Center for Creative Leadership, recognize that empathy at work creates connections, improves social skills, and enhances collaboration. In spite of its benefits, practicing empathy can exact a steep price. Psychologist Adam Waytz warns against “compassion fatigue” and burnout from empathy and suggests that giving people breaks that allow them to focus on their own interests helps with mental health. When I started teaching my “Black in America” section of English 1102 during the global pandemic, I was hyperaware of how mentally and emotionally drained my students already were. I wanted to support their mental health as they focused on developing empathy, especially given how many representations of trauma they would encounter in their experiences of media portrayals about Black history.

Taking a cue from the long history of Black resilience, I turned to art as a method for processing in the Creative Reflection assignment, where students were tasked with creating a multimodal artifact that generated empathy for their experiences learning about the history of being Black in America. As Waytz advises, this assignment made space for the emotional labor of the class, having students present an analysis of a mode of communication they already considered themselves experts in, rather than focusing on one where they struggled. This analytical celebration served a dual purpose, both ensuring that students were leveraging their strengths to hone their communication skills and helping me assess the assignment later.

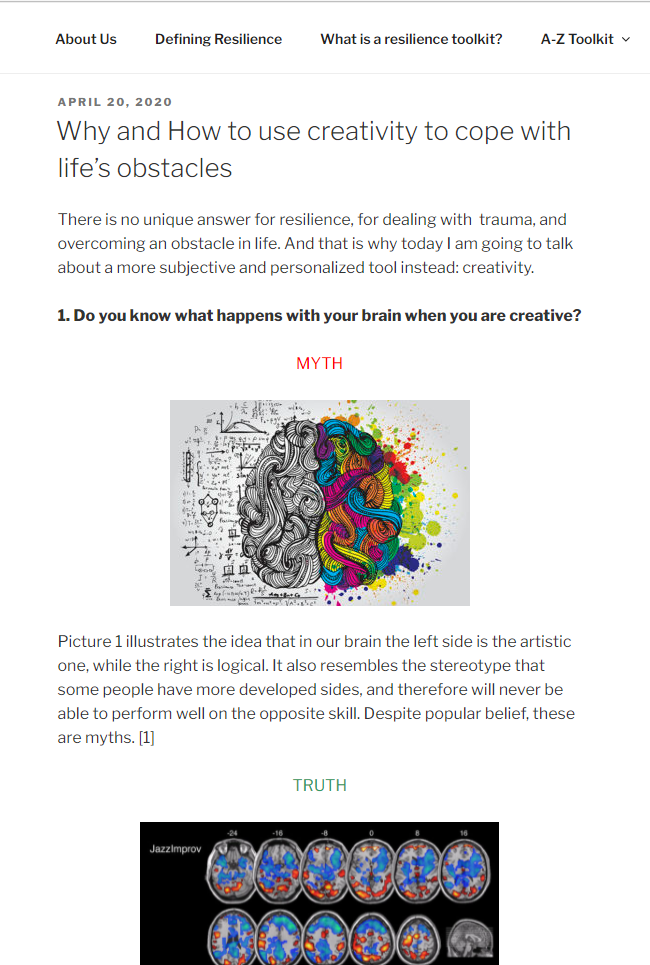

The open-ended nature of the assignment and the different areas of communication expertise led to a wide array of projects. Some students used numbers, such as the student who created a webpage that told the story of discrimination through data analysis. Other students were inspired to tell the stories of Black folks in their communities, such as the student who interviewed the Black owners of several Atlanta coffee shops and wrote about them on her blog. The wide range of projects included a sculpture representing how the class had changed a student’s mind, a comic about a student’s own experiences with race, a playlist representing the history of Black music, and a photography exhibition on Black joy. One student, who identified interpersonal communication as her mode of expertise, created a community art project where she had conversations about race with participants as they added their handprints to an image from John Lewis’s comic memoir March, which we had read in class. To the right, you’ll see the work of a student who chose to create a visual image about race and medicine. The central, Black figure screams into a megaphone, asserting their subjectivity, but is virtually crowded out of the space by the media headlines about the negative experiences of Black folks in medical contexts.

Aspects of the Creative Reflection assignment could easily be adapted to any literature classroom, whether through the analytical celebration of strengths or through the creative component, as single-class activities or as a major assignment sequence. However, it is important to incorporate time for emotional processing, and I urge instructors to remember that giving students a break from empathy is crucial to their mental health.

Notes

[1] To note, I was extremely clear and consistent about the fact that we were in a composition classroom and not in therapy, and that there was no need to disclose or share personal stories. I ensured students were aware of Georgia Tech’s mental health services, facilitated their accessing them, and had a professional from the campus Counseling Center come to class.