When I mention that I use Twitter in my first-year writing courses, I am often met with both intrigue and skepticism by students and faculty alike. If writing courses are supposed to be focused on nuanced thinking, careful research, and rhetorically sophisticated arguments, what can students possibly learn from writing 140-character social media posts? In the last year, Twitter has taken an increasingly prominent place in national and international conversations, political and otherwise, drawing a sharper focus on how Twitter can shape and improve student communication.

Last semester, Spring 2017, is the third time I have taught a course that integrated Twitter as a vital component of communication. Rather than using social media to be “on trend” or create a flashy electronic requirement, this course used Twitter as a platform for students to brainstorm ideas and engage with Twitter’s growing academic communities. This particular course, English 1102: Rhetoric and Propaganda of YA Dystopian Fiction, looked to Twitter as an example of electronic communication that is widely used in journalistic, academic, and other professional settings. By integrating “livetweeting” into the reading, discussion, and brainstorming phases of the writing process, Twitter allows students to create an interactive record of their learning, project development, and research habits that can be useful for all writers, and especially first-year college students.

Teaching with Social Media

Regardless of the course topic, teaching with Twitter is always an opportunity to teach students how to interact with a larger public and reach that audience effectively. Many employers expect recent college graduates to know how to use social media tools by virtue of their age, generational placement, and, especially in my students’ case, Georgia Tech’s reputation for using innovative technologies in the classroom and laboratory. Therefore, modeling professional uses of social media platforms, as well as giving students a low-stakes opportunity to practice distilling their ideas into 140 characters and engaging in important conversations in a public (digital) space can help those same students avoid the kind of embarrassing faux pas that can end a career or be found on the front page of Buzzfeed as a PR disaster.

While twenty-first-century college students are frequently touted as “digital natives,” a surprising number of them are relatively inexperienced in social media spaces beyond their immediate friend and family networks. An informal poll of my students at the start of the semester indicated that the majority (77%) agreed with the statement that “social media is a valuable tool for professional networking.” However, an overwhelming number (90%) also indicated that social media is “a valuable tool for keeping in touch with friends and family,” and their primary motivation for using those platforms. The successful integration of Twitter into a course can have very real stakes for students, not only in the short term of class performance and grades, but also in the long term. Finding innovative and engaging ways to integrate social media into the composition classroom then becomes not only pedagogically useful, but also an important part of contemporary communication education.

To talk about teaching with social media, however, is also to recognize the privilege of working in a space like Georgia Tech, where every student is required to have their own laptop, and 100% of my students owned their own smartphones. Faculty members interested in teaching with social media will also want to think carefully about privacy issues and familiarize themselves with the FERPA policies at their institution; I ask students to create a new Twitter account specifically for the class, and allow them to decide if they want to use their real name or an anonymous pseudonym. Finally, teaching with social media requires a good deal of trust on the part of the instructor. There can be no “laptop bans” in this kind of course, and when half of the students have their heads buried in their smartphones, the instructor must trust that it is because they are livetweeting discussion or responding to Twitter threads, and not because they are checking fantasy football scores. While all of these elements are important to consider when incorporating Twitter (or any social media platform) into a course, transparent discussions about these policies can actually help to model responsible social media use and lead to discussions about the pros and cons of engagement with public-facing electronic modes of communication in a variety of contexts.

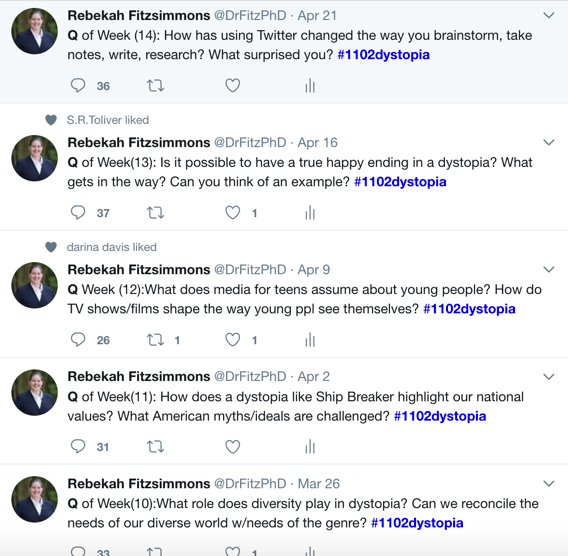

A sample of some of my “Questions of the Week,” via Twitter.

Pedagogical Framework

I had three major goals for the students using Twitter in this course:

- to create a space for public, low-stakes brainstorming,

- to enable discussion outside of traditional face-to-face, seminar-style communication, and

- to help students engage with new avenues for research and collaborative brainstorming, specifically by accessing academic communities emerging on Twitter.

To accomplish these goals, I first worked to lower the entry barrier into the digital space of social media. Engaging in public discourse can be fairly intimidating at first (for students and professionals alike), and Twitter is no exception. Instructors should not assume that their supposed “digital natives” are familiar with any social media platform, nor should they assume that students will be comfortable just jumping in. I often begin by walking students through setting up a Twitter account––for instance, asking them to include an image and a biography that identifies their role as students in a course on YA dystopian fiction. This leads to conversations about the communication norms within a given community, and discussions surrounding the concept of social niceties, unspoken communication guidelines, and nonverbal communication in both face-to-face and digital interactions. For example, we talked about the assumption that “eggs” or blank Twitter profile photos are often associated with bots, trolls, or Twitter newbies. We discussed how, just like putting on a suit for the career fair, following the social norms of an online space greatly increases the likelihood of experienced users engaging with students in productive ways.

In terms of formal requirements, each student was expected to produce approximately ten tweets a week; in order to count toward the class requirement, each tweet must include the course hashtag (last semester it was #1102dystopia). Given the 140-character limit of a tweet, ten tweets is the equivalent to less than one page of prose.[1] For this course, those ten tweets encompassed three specific requirements:

- respond to one “Question of the Week” tweet from the instructor,

- post a discussion question based on the reading before the start of each class, and

- livetweet the readings/viewings from the week, which includes the possibility of engaging with peers or other Twitter users.

Goal One: Create a Space for Brainstorming

To achieve the first goal, I asked students to livetweet while they read or watched the texts assigned for each class. Livetweeting is a common Twitter feature, most often used to post stream-of-consciousness comments and reactions to live events, such as the Super Bowl, the latest episode of Scandal, presentations at academic conferences, or the tallying of election results. In using the term “livetweeting” in the assignment parameters, I intentionally invoked the highly informal, playful tone most often used in this kind of commentary, while also drawing upon the community nature of the practice. When students livetweeted class screenings of The 100 or The Hunger Games, they had the opportunity to engage in this simultaneous viewing practice. They could ask questions, respond to controversial opinions (#teamGale v. #teamPeeta), make jokes, and post analytical ideas as they thought of them.

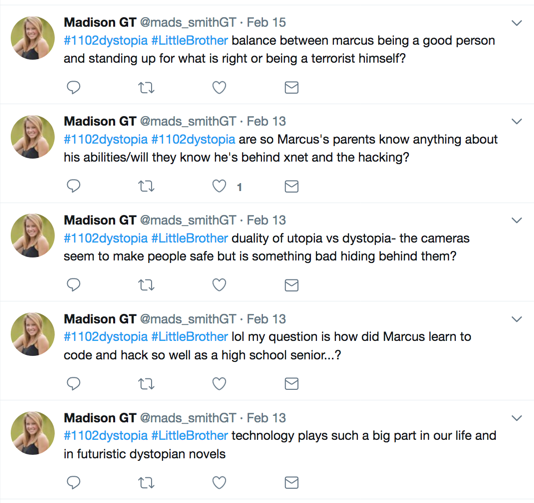

At the same time, invoking the concept of livetweeting while completing the course readings disrupts the community element of this practice: while the whole class community is reading the same selection from Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother over the same weekend, these readings are rarely simultaneous. This alters the function of the livetweet from a temporal, community-shared experience to one that more closely resembles keeping a reading journal. As students read, they record and share their thoughts, reactions (both positive and negative), ideas, and analysis in real time. The public nature of this journal allows for other Twitter users, both fellow students and not, to weigh in and argue for or against a particular reading, or to draw connections with other texts. Days later, this interactive reading journal becomes an especially fertile resource for students as they discuss the readings in class; weeks later, it acts as a valuable brainstorming record while seeking out topics for an independent research paper.

A thread of Madison Smith’s livetweets, via Twitter.

Goal Two: Expanding Discussion Modes

Responding to student feedback from previous semesters, I have also worked to integrate Twitter as an everyday part of my classes. Encouraging students to use Twitter as a space to livetweet class discussion, to post supporting evidence for claims made during those discussions, or as a space to critique and respond to peer presentations provides students with an additional method of class participation.

Some of the most valuable expansions of discussion occurred on days when students presented independent research to the class. Twitter afforded the class opportunities both to critique the presentations, as an exercise in peer review, and to ask and respond to questions. The critiques that came via Twitter were highly supportive and encouraging; many audience members framed their comments as successful techniques that they hoped to “steal” or model in their own future work. Many students in the audience posed questions that they had about each presenter’s research, and those presenters often responded directly to questions by pointing peers toward additional resources, expanding beyond the outline of the material presented in front of the class. The supportive and collaborative space for learning crossed between the physical classroom space and into the digital; students had the opportunity to engage more thoroughly with researchers whose topics interested them while helping peers to improve the style, organization, and techniques of their presentations.

While my pedagogical intention was to create a secondary mode or backchannel for students to participate in or continue discussion outside the walls of the physical classroom, feedback from my students suggests to me that Twitter affords students who struggle with oral participation new ways to become more active members of the in-class community. Students expressed an appreciation for the opportunity to participate in discussion via Twitter, as it helped them to add their own commentary and ideas, despite anxieties about speaking in front of others. International students, in particular, indicated that Twitter allowed them opportunities to “speak up” in a way that they normally felt unable to do in fast-paced classroom discussions conducted in their second (or third, or fourth) language. Without Twitter, the hugely valuable observations of students from non-U.S. contexts on topics of discussion––freedom of speech, privacy rights, surveillance culture, and international conflict––would likely have been lost or restricted.

The biggest excitement last semester came when students got responses from the authors we were reading and discussing. A number of students had digital interactions with authors of books that they read independently, as well as the authors of some of the core dystopian readings: Cory Doctorow and Paolo Bacigalupi. Students wrote about these interactions as a highlight of their Twitter use in their end-of-semester portfolios. Other students reported conversations with students from as far away as Denmark and Sweden asking about the course––or in one case, asking permission to use the Prezi that the student created as a source for their own research. In this way, students found gateways into a larger community of scholars pursuing similar intellectual challenges; the work of our class no longer seemed isolated or divorced from the reality of the world around them. The more that the students engaged with the community of scholars, authors, and students of dystopian literature online, the more they felt like members of that same community.

Future Use of Twitter in Composition Courses

While the use of Twitter as a space for informal brainstorming and expanding classroom discussion was highly successful, my third goal–– convincing students that Twitter could be a beneficial source for research––may need additional refinement. My own Twitter use as an academic reflects a highly collaborative space within niche academic communities in which scholars share valuable resources, debate current events, and discuss relevant theoretical frameworks. I hope to continue to re-examine my own approach to helping students access this kind of online community, though it is likely that the most beneficial scholarly networks take more than a semester to build, and so may be beyond the scope of a single-semester undergraduate course. However, I remain committed to the work of making my classroom visible within the academic Twitter-verse in order to help students situate themselves within the emerging digital discourse communities as representatives of Georgia Tech. I am currently teaching with Twitter in my 1101 class this fall: if you are interested in banned books, literary prizes, and bestseller lists, feel free to follow our course hashtag, #1101List.

Notes

[1] Twitter has recently started experimenting with 280 character tweets, which would give students a little more rhetorical space to work with and potentially change the way I structure this assignment.