While Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) is usually remembered as the quintessential American road novel, the slightly earlier debut novel of Kerouac’s friend and fellow Beat William S. Burroughs, Junky (1953), is equally expansive in its exploration of the North American continent. Kerouac’s roman à clef—first mapped by the author himself–ends in what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari call a “return to the native land” (133): the protagonist Sal Paradise goes to live with his aunt in New York just as Kerouac went to live with his mother in real life, falling in love with a girl in a symbolic re-closing of the American frontier. Burroughs’s novel contains no such happy ending. Part pulp thriller, part anthropological survey of the cultural habits of heroin and its users, published two years after Burroughs killed his wife Joan Vollmer in a drunken game of William Tell (a fact the novel problematically elides), Junky‘s escape narrative is one of endless pursuit. From New York to the Federal Narcotics Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, from New Orleans to the Rio Grande Valley, and from Mexico City to Colombia, Burroughs’s reader follows the author’s stand-in, the pseudonymous William Lee, as his addiction chases him further south in search of “the final fix”: yage, a mythical Amazonian cure, said to “increase telepathic sensitivity” (149-50). It was Burroughs’s initial wish that the novel be titled Junk and not Junky (nor Junkie, as it was spelled in the original Ace Books edition, Fig. 1) in order to emphasize that the book’s protagonist is the drug and not the addict. At the center of the novel is a cat and mouse game, the story of a predator hunting its prey–a narrative perhaps no more apparent than in the novel’s geography, scattered along roads much darker than Kerouac’s search for the heart of Saturday night.

Figure 1 The 1953 Ace Books cover of Junky, including the original spelling of the title and Burroughs’s pseudonym, William Lee. Image available at https://junkphilosopher.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/junkieburroughsacecover.jpg.

This semester, I’m teaching an English 1102 course called “Literature on the Drugs.” Since January, my students and I have traced the relationship between literature and narcotics in the modern era from the emergence of recreational drug use at the dawn of the nineteenth century (in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan; or, A Vision in a Dream: A Fragment” [1797/1816] and Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater [1821]) through the present day. My interest in exploring this subject in a composition course primarily concerned with critical thinking, rhetorical analysis, research, and argumentation was sparked not only by the historical coincidence of literature and drugs–Jacques Derrida notes that both literature, as distinguished from poetry and belles lettres, and drug addiction were contemporaneous phenomena in Europe, “dating from the sixteenth or seventeenth century” (27)–but our tendency to talk about drugs using the same language and metaphors that we use to talk about writing. On the one hand, we might praise an essayist’s “intoxicating” prose; on the other, we might cite one poet’s “influence” on another. Texts can be “on” one another in the same way that a human can be “on” any given substance. This idea is one of the primary focuses of my dissertation, as well as my current research.

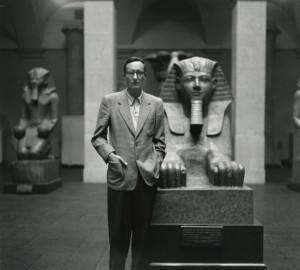

Figure 2 Burroughs, photographed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Allen Ginsberg in 1953. Image available at http://www.howardgreenberg.com/artists/allen-ginsberg/featured-works#7.

Aside from Emily Hahn’s “The Big Smoke” (1969), a journalistic account of Hahn’s short-lived addiction to opium as a foreign correspondent in China in the 1930s, Junky was the first instance of American literature that I asked my students to read. Much less experimental in its form than the novels for which Burroughs is better known–Naked Lunch (1959), especially–Junky is in fact an example of genre fiction: a crime novel, first published in an omnibus edition alongside Maurice Helbrant’s true crime memoir, Narcotic Agent. In class, I encouraged my students to approach it as such, listing the conventions of crime fiction on the blackboard, and subsequently discussing Burroughs’s various adherences to departures from these conventions. Of particular interest were Burroughs’s use of and fascination with the language of drug culture, perhaps best illustrated in the entry for “Hep or Hip” in the novel’s glossary: “Someone who knows the score,” Burroughs writes, “Someone who understands ‘jive talk.’ Someone who is ‘with it.’ The expression is not subject to definition because, if you don’t ‘dig’ what it means, no one can ever tell you” (153).

But it was Burroughs’s fastidious attention to location, and not language, that encouraged me to have my students map the novel. As a graduate student, I found myself enamored with Franco Moretti’s Atlas of the European Novel, 1800-1900 (1999), a seminal work in the field of literary geography, and I had a faint knowledge of digital humanities projects using Google Maps and other online tools to map the geography of various novels (see, for instance, Placing Literature). It was not until noticing the geographical precision of Burroughs’s description, however, that I thought about mapping as a potentially valuable pedagogical tool. For instance, Burroughs writes of one of Junky‘s most significant locations as follows:

103rd and Broadway looks like any Broadway block. A cafeteria, a movie, stores. In the middle of Broadway is an island with some grass and benches placed at intervals. 103rd is a subway stop, a crowded block. This is junk territory. Junk haunts the cafeteria, roams up and down the block, sometimes half-crossing Broadway to rest on one of the island benches. A ghost in daylight on a crowded street.

. . .

You could always find a few junkies sitting in the cafeteria or standing around outside with coat collars turned up, spitting on the sidewalk and looking up and down the street as they waited for the connection. In the summer, they sit on the island benches, huddled like so many vultures in their dark suits. (32-3)

A junkie’s environment and surroundings, Burroughs seems to argue, are as crucial to his identity as his words are, and I hypothesized that by creating a representation of the novel that is visual, geographical, and interactive while still rooted in the text, something worthwhile and previously hidden would emerge.

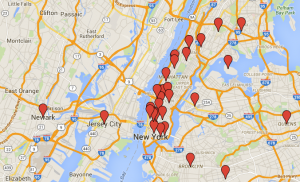

Figure 3 The portion of the novel set in New York contains references to thirty-three different locations across the metropolitan area, the protagonist’s mobility necessitated by the vastness of the city, and aided by the ease afforded by the Subway.

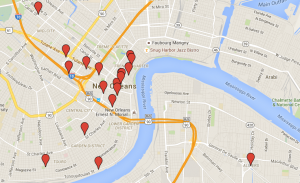

Figure 4 In New Orleans, Lee’s world can be seen to be much smaller, a consequence not only of the city’s size, but the increasing severity of his addiction to heroin.

Figure 5 In Mexico City, Lee’s world is smaller still, mostly contained to a few blocks in the Colonia Centro. It is here where Burroughs’s narrative climaxes: the law closing in on Lee, his addiction to heroin isolating him almost completely.

The process of mapping the novel was relatively simple: I pinned all of the locations referenced using Google Maps in advance, approximating only when necessary (though less often than one might imagine, as Burroughs is for the most part remarkably specific in his description). In our third class session devoted to the novel, I assigned each of my three sections a city–New York, New Orleans, and Mexico City–and divided them into groups of four, providing each group with a set of between five and ten pages (the novel is quite short, just over 150 pages). From there, students located relevant passages from the novel and paired each passage with its corresponding pin on the map. Some locations in the novel are referenced many times; others, only once or twice. I asked the groups who finished first to fill in the gaps, and within three hours, my students had completed the project, producing a representation of the novel that can be read geographically and nonlinearly–an online resource for Burroughs fans and scholars alike, as useful as it is entertaining.

What can a map tell us about a novel? In the case of Junky, quite a bit. The general shape of the map is that of a downward spiral, a narrative structure so common in the literature on drugs that it has itself become a cliché. By zooming in on individual cities, it is easy to see the role geography plays in Burroughs’s narrative: New York’s expansive size and public transportation allow for great mobility, often requiring Lee to travel great distances to procure the drug (Fig. 3); hiding out from the law in New Orleans, a much smaller city, Lee’s movements are more limited (Fig. 4); and despite the fact that Mexico City is the largest metropolitan area in the western hemisphere, as a foreigner deep in the throes of “junk sickness,” Lee is mostly confined to a few blocks within the city’s downtown center (Fig. 5). Were my student-cartographers to track Burroughs’s motions beyond Junky, they would likely find him in Tangier, Paris, and London, where he spent most of his career-in-exile before returning to the U.S. in 1974–first to New York, and then Lawrence, Kansas, where he died in 1997.

As we enter the section of the course dealing with narcotics’ global spread–as a target in the War on Drugs, a commodity bought and sold in an increasingly digitized marketplace–I look forward to encouraging my students to continue thinking geographically, visually, and multimodally about literary texts, their distribution and consumption no less complex than international drug traffic: moving through black markets, crossing borders.

If you would like to learn more about current events in our classes and scholarship connected to digital mapping, consider reading Ben Bergholtz’s and Alok Amatya’s interview with their students in “Mapping the Maximalist Novel: A Dialogue between Students and Teachers.”

Works Cited

Burroughs, William S. Junky: The Definitive Text. New York: Grove, 2012. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. New York: Penguin, 2009. Print.

Derrida, Jacques. “The Rhetoric of Drugs.” Trans. Michael Israel. High Culture: Reflections on Addiction and Modernity. Ed. Anna Alexander and Mark S. Roberts. Albany: SUNY P, 2003. 19-43. Print.