Regular readers of TECHStyle may remember my mentioning, back in September, my plans to use interactive fiction (“IF”) computer games in my multimodal composition classes. After two semesters of teaching students to read, play, and write IF games, I can say that the experiment was mostly a success. While we faced a few frustrations (largely coding-related) along the way, we ended up gaining some invaluable rhetorical perspectives and practices, and producing a number of fun, thoughtful, and affecting games to boot. In this first of two posts, I’ll explain why I think IF is especially valuable in the composition classroom. In a later post, I’ll lay out some advice, resources, and recommended games for those of you thinking of experimenting with this genre in your own courses.

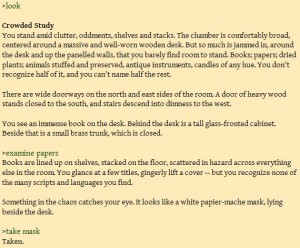

Note, in this excerpt from Plotkin’s tutorial game, how the player-character and the narrative voice take turns typing to each other.

What Is Interactive Fiction?

To understand how these games helped us learn rhetoric, you first need to know what they are. If you missed IF’s commercial heyday in the 1980s, when Infocom was putting out “text adventures” such as Zork and its successors, you may never have seen one of these before. (You might enjoy playing around with a tutorial game, Andrew Plotkin’s The Dreamhold, which is designed for newcomers to the genre.) Basically, interactive fiction, as I’m using the term here, is a second-person role-playing game in which the reader/player becomes a sort of associate author, typing in commands stating what she wants her character to try next. The game “types” back, incorporating the user’s choices and input; thus, the story may proceed quite differently for a player who types “attack the troll with the nasty knife” than for one who types “ask the troll about the opera.” Over the last two decades, an amateur IF scene has mostly replaced the professional one, with enthusiasts swapping games, hints, and authorial advice online. Although some works incorporate limited visuals and sound to good effect, the core of the genre has always been verbal; the game writes a bit of story, the player writes a little more, and so onward.

Reading/Playing IF: Games as Literature

What is gained by treating IF texts as “the reading” in a composition class? I’ve found that these works can lend action and agency to students’ reading strategies. While traditional literary genres certainly call for some interplay between author, text, and reader, most print texts themselves are relatively static and often enforce a common, linear reading experience that limits the variety of possible interpretations and responses. When a student plays an IF game, however, it is much more difficult for him to remain passive or to rely on commonplace or majority readings, because he is literally helping to write the game as he goes. His text will be different from his classmates’ because of the precise nature of his engagement and his response.

Because the player often must solve a puzzle for the story to change and progress, playing IF can teach students to pay close and careful attention to a text, dissecting it for details that they will be able to use. (If the player fails to notice the baron’s sullen demeanor in the first scene, she may not explore the option of cheering him up with flowers later.) Moreover, and more vitally, the variety of possible pathways in an IF game invites students to consider their own rhetorical moves in other contexts as more naturally interactive, able to anticipate and provoke different responses from different readers. Put another way, IF enlivens and concretizes students’ understanding of how they and their work might relate to audiences. After our studies of IF, many of my students were able to imagine specific reader reactions much more actively and vividly in their reflective writing.

Writing IF: Games as Composition

The most important payoffs, however, came from asking my students to write their own short, rhetorically driven games. Learning Inform 7, a “natural English” programming language designed for writers rather than coders, allowed them quickly to grasp how stories could be created from their digital underpinnings. (A brief Inform 7 video tutorial that showcases its ease-of-use is here.) Working in teams of five forced them to manage very difficult writing and revision processes. Because any change in one part of the game — character, plot, item descriptions, narrative voice — might have repercussions on several others, they had to implement systems for drafting, collating, revising, and checking one another’s work. (I’m not oblivious, of course, to the advantages I had in using this assignment here at Georgia Tech. My students all had computers and nearly all of them entered my class with some programming experience; even so, learning to code took more time than I wanted to allow for it.) Many of the resulting games were especially noteworthy for the quality of their prose and the intellectual depth of their rhetoric; I think that because each scrap of writing had to pass through multiple hands and code drafts, the students paid extra attention to polishing their work and ensuring a hearing for their game’s message.

Although several student games had somewhat commonplace rhetorical effects (for example, one group steered an amnesiac pirate through various alcohol-related shipboard puzzles and challenges in order to persuade potential players not to drink so much), the best games exploited the singular rhetorical situation of the IF player-character to investigate questions of subjectivity, selfhood, and self-knowledge. One game, set on a desert island after a plane crash, alternated between scenes of wilderness survival and flashbacks to the protagonist’s former life. In the flashbacks, the player had to “remember” learning about scientific principles (e.g., how magnetizing a needle works), gaining knowledge of how to approach challenges on the island; the game thus became an interesting and provocative meditation on the relationship between knowledge and memory. Another game, set in a prison cell, used various foils (the player-character’s cellmate, his reflection in a mirror, his remembered past) to ask how much we really know about our own motivations and systems of morality. This complexly conversational game went through extensive testing and revision, provoking a revelatory comment from a student author: “It’s the best feeling when you’re watching somebody play your game, and they think of something to do next, and you can say, ‘The reason you had that reaction is because my writing and code worked!'” The process, in other words, gave students direct insight into how their writing choices work upon readers and how they might revise them to work differently, insight that will serve them well in future composition projects.

Jonathan Kotchian. Photo: Kim Armstrong.

About the author: A Brittain Fellow since 2012, Jonathan Kotchian (PhD and MA in English, University of Connecticut; BA in theater, Yale University) is revising his first book project, which shows how the figure of the superior author in early modern England co-evolved with satire. His second book project, which continues his investigation of “insider” literature accessible only to certain readers or viewers, explores the relationship between concepts of intelligence and literary taste. His interests range from Shakespeare and Milton to using theatrical training techniques in the multimodal composition classroom, where he asks his students to foreground their own motivations, self-presentations, and affective responses. Key interests: early modern literature, composition, authorship, satire, intelligence, drama, theater, interactive fiction games, and digital humanities. He can be reached by e-mail at jonathan.kotchian@lmc.gatech.edu or jkotchian@yahoo.com, and via Twitter @JonKotchian.

Pingback: Teaching Composition with Interactive Fiction, Part Two - TECHStyle

Interactive Fiction (formerly referred to as Text Adventures) are a cross between reading a book and playing a game, where you control the main character….