When first designing my English 1102 course, Multimodal Mars, I wanted to integrate the Georgia Tech Science Fiction Collection, which contains a large number of magazines such as Planet Stories, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Astounding Stories (among others). My reason for this was twofold: I felt that students would better understand science fiction of the mid-twentieth century by having firsthand experience with short stories, cover art, and illustrations, and I planned to have students digitize these materials in order to make them more widely accessible.

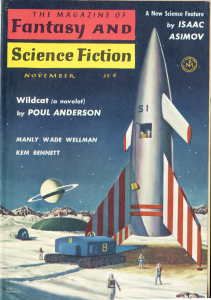

Cover of the November, 1958 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, illustrated by John Pederson, Jr. Uploaded by Dan Century and used via a Creative Commons license. Image available at https://www.flickr.com/photos/dancentury/7125737351/.

While my class deals specifically with Mars, we often discuss the importance of science fiction (SF) as a rhetorical lens through which individuals speculate about real world issues such as empire and colonization (such as in The Martian Chronicles), ecological devastation, and the construction of gender roles (see C.L. Moore’s “Shambleau”). But, as a genre, SF is constantly evolving in response to historical and social changes. An archive is thus a valuable tool, as it acts as a time machine that students can enter in order to explore materials that encapsulate SF as it existed in days gone by. While the GA Tech Science Fiction Collection also contains contemporary materials, I had students focus on 1930-1970, a time during which science fiction magazines not only emerged as a popular form but also published the early works of giants of the genre such as Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke.

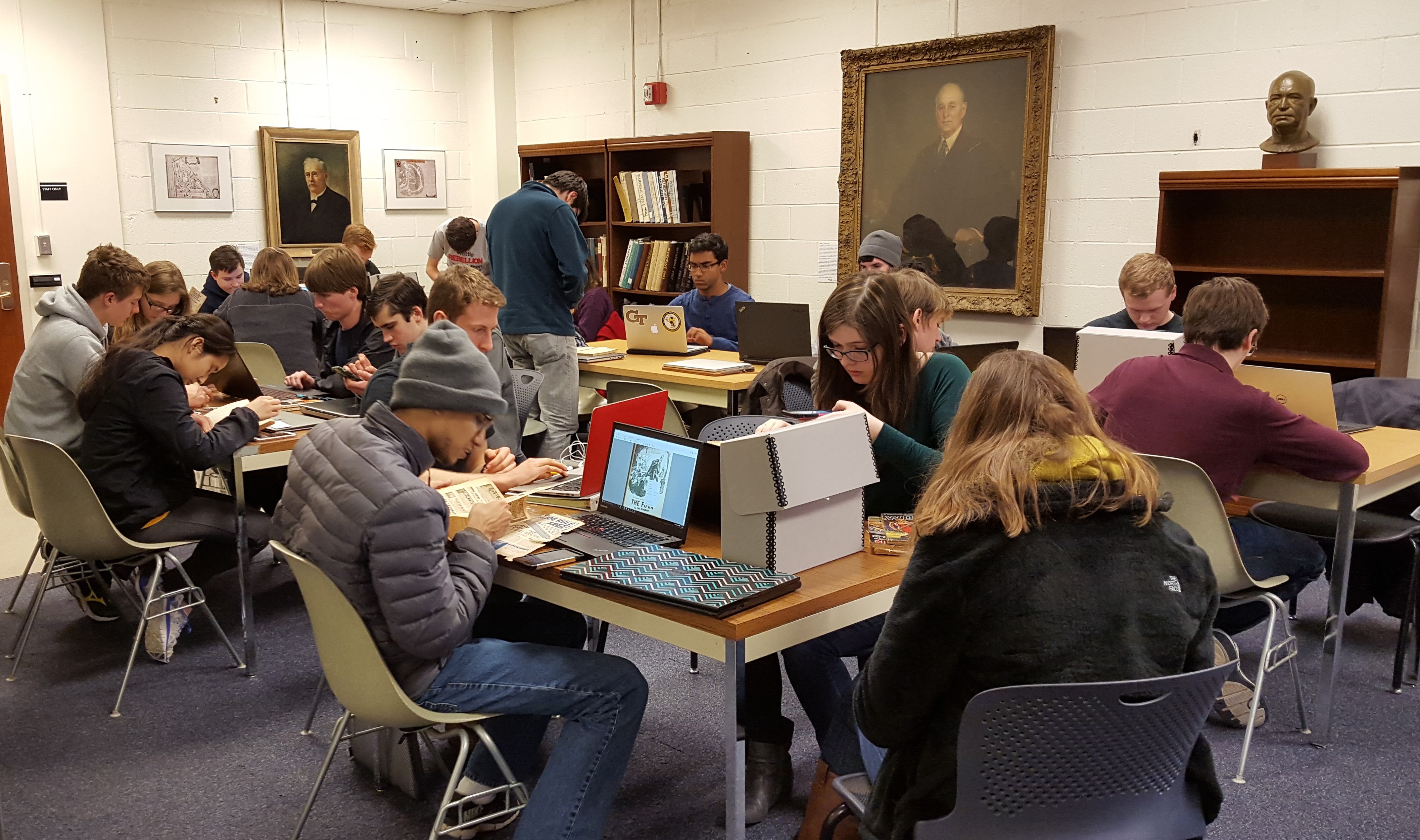

Rather than having students individually request materials, I asked Jody Thompson (the head of the GA Tech Archives) to locate magazines from within the collection, which she pulled for our class to use in archive’s reading room (located here). Each student was responsible for browsing the magazines and locating a story that was both set on another world and which he or she felt embodied the science fiction genre (the topic of a paper which accompanied this assignment). However, it was not enough to have students simply read these stories and then place the magazines back in their storage boxes, never to see the light of day until another person chose to access the materials. Instead, I asked each student to scan the story, its inclusive illustrations, and the cover of the magazine, thus creating an electronic artifact that would be accessible online. A free application, CamScanner, allowed students to use their smartphones to produce high-quality scans for inclusion in a digital archive. I chose this application based on my familiarity with it, but also recommend it as a tool for individuals interested in digitizing material artifacts.

The students of ENGL 1102: Multimodal Mars, section P3 scanning their magazines for use in Omeka. Photograph taken by Andrea Krafft, with permission of the students.

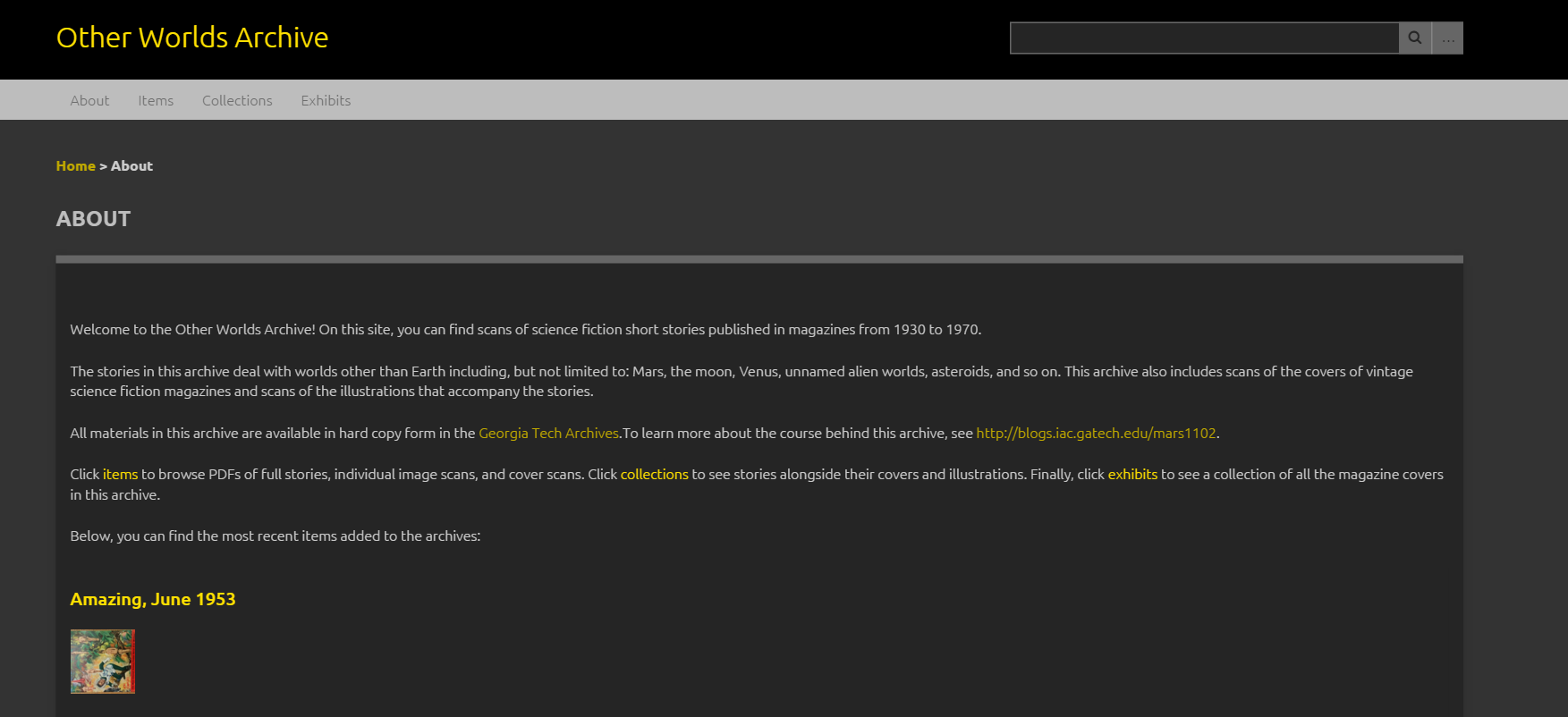

On the advice of Steve Hodges (IAC’s Director of IT Services), I chose to use Omeka as the platform for the class’s archive. While Omeka is not eminently customizable (compared to platforms such as WordPress), its sites have a simple layout and are easy to use. I found that students had little difficulty uploading their items and adding metadata, which future users can search if hoping to find a story from a specific author or magazine. Of course, the archive that the students assembled contains only a sample of science fiction magazines, but I hope to build this artifact with future classes and with the assistance of Georgia Tech’s wonderful archival librarians.

A screenshot of the Other Worlds Archive, taken by Andrea Krafft. Click the image to access the archive’s login portal.

To view the class’s archive, first log in at http://omeka.iac.gatech.edu/OtherWorldsArchive/admin (using GA Tech credentials) and then click “Other Worlds Archive” in the top left hand corner to view the public-facing page. At this stage, the archive is limited to GA Tech users, but, if we can attain permissions for the materials, we can reach a wider audience of students, scholars, and fans of science fiction. I invite other GA Tech faculty and students to contribute to this project, or to pursue building digital archives of their own (for more information about possible projects, see http://www.library.gatech.edu/archives/faculty_info.php). The Science Fiction Collection is only part of the GA Tech Archives, which also contain records of the school’s history, materials for architectural design, and even first editions of Isaac Newton’s Principia. Spending time in the archives allows students to come into contact with rare or little-known materials and thus expands their opportunities for knowledge beyond canonical texts.

Furthermore, the archives provide us with another means of exploring the centrality of WOVEN (written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal) communication to the learning process. By having hands-on time with science fiction magazines, students were able to better appreciate how early publications are multimodal artifacts in their own right that blend writing with visual design (the W/V in WOVEN). Additionally, the online archive that they created reaches beyond the classroom, demonstrating the importance of electronic communication to scholarly research (the E in WOVEN). In the end, I found that this project achieved its goals, as students attained a more advanced understanding of SF as a genre while simultaneously building an artifact that I hope will assist future students interested in the rhetorical and cultural significance of science fiction.