A COVID-19 “die-in” demonstration at Georgia Tech on August 17th. Eric Stirgus, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 24 Aug. 2020.

by Alexandra Edwards, Corey Goergen, and Kent Linthicum

We wrote this article before the fall 2020 semester to show the disparity between non-tenure-track faculty and tenure-track faculty in our school at Georgia Tech. In addition, we hoped the method we outline below would be one other faculty could use to see how their schools allocate risk. Despite the timeliness of the article, multiple enquiries to publishers received no or delayed responses. Nevertheless, we believe the article still is relevant to teaching during this pandemic, as well as the coming winter/spring. The version we present here—which should have been published around August 1st—is unchanged in order to show what we were worried about then and how these concerns remain un-addressed.

In the COVID-19 era, who gets to teach safely at a distance?

As colleges and universities unveil (or change) their fall plans to respond to the pandemic, how is risk distributed across the university faculty? After a summer spent teaching remotely and arguing for the ability to continue doing so into the fall and with coronavirus cases spiking in Georgia, we decided to try answering this question. We found that, in our school, the burden of preserving the on-campus experience falls disproportionately upon university faculty who are in the most precarious positions with respect to pay, insurance, and long-term employment.

The School of Literature, Media, and Communication (LMC) is Georgia Tech’s hybrid English and mass communication department, covering traditional English and communication disciplines like literature, creative writing, film, composition, digital media, and games. And, like any modern department, the faculty comprises a range of positions, including endowed professors, academic professionals, and graduate students. What makes LMC unique is its large number of postdoctoral teaching fellows like ourselves, who perform the labor often done by graduate students in more traditional English departments: teach required general education classes, mostly for first-year students. In a normal year, this is an unremarkable arrangement. But 2020 is far from a normal year.

Tech’s 2020 fall plan divides classes into five possible modes: residential spread, hybrid (hands-on, touch points, split), and remote. What is important here is that the residential and hybrid modes still require face-to-face interaction. Remote courses do not. We wondered, ‘Who is asked to teach in these face-to-face modes and bear the most risk?’

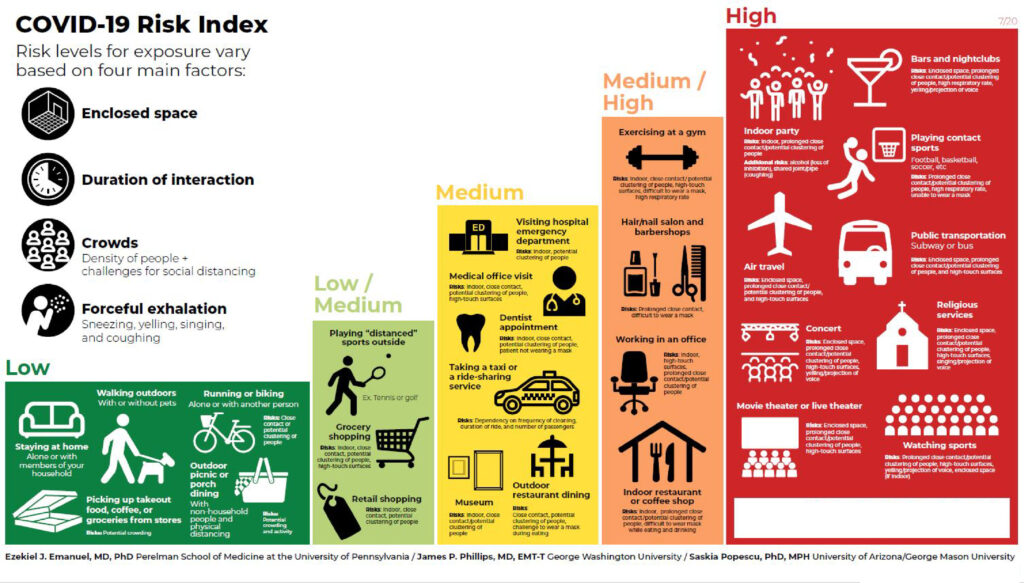

This chart does not categorize classrooms. But it would likely fall either in the “Medium/High” to “High” categories depending on a number of factors. “Covid-19 Risk Index.” Ezekiel J. Emanuel, James P. Philips, and Saskia Popescu, 2020.

To answer this question we used Georgia Tech’s schedule of classes—listed on its web access system, OSCAR—and counted. We tallied the total courses taught by our school and sorted them by instructor status and mode.

It is important for us to note that our numbers are specific to a date, July 30, 2020, and because we are not working from the official spreadsheets—only the data that is publicly accessible—there will likely be some errors. Any minor issue with the numbers, though, would not detract from our primary point: the current arrangement exposes contingent faculty to the health risks of the pandemic at a higher rate than their tenure-track colleagues.

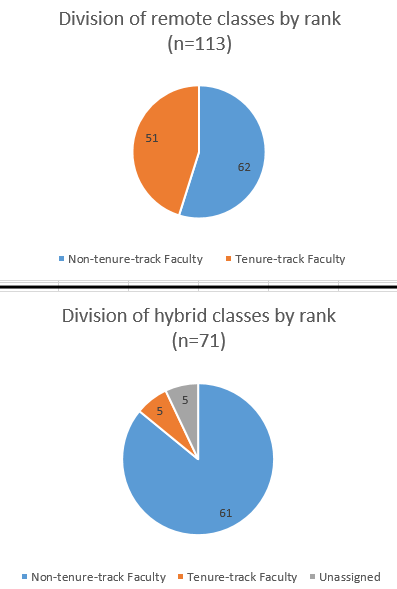

This fall semester, LMC is offering roughly 184 courses (listed as either ‘ENGL’ or ‘LMC’). In this article, we define a course as a set time in which students meet collectively with a professor to study a topic selected by the professor. In other words, we are not including entries that are more individual or self-directed, like dissertation or thesis hours. We leave these out because there is no certainty that faculty will meet in person with their students for these classes; e-mails, phone calls, or video chats are just as likely. Therefore, of these 184 classes, 71 (or 38%) are designated hybrid, and 113 (or 62%) remote. This division aligns very roughly with Georgia Tech’s “Moving Forward” plan, which emphasizes a return to campus. Among remote classes, the labor is divided with equity: 62 (or 54%) of the 113 remote classes are being taught by non-tenure-track faculty, whereas 51 (or 45%) are being taught by tenure-track faculty.

This fall semester, LMC is offering roughly 184 courses (listed as either ‘ENGL’ or ‘LMC’). In this article, we define a course as a set time in which students meet collectively with a professor to study a topic selected by the professor. In other words, we are not including entries that are more individual or self-directed, like dissertation or thesis hours. We leave these out because there is no certainty that faculty will meet in person with their students for these classes; e-mails, phone calls, or video chats are just as likely. Therefore, of these 184 classes, 71 (or 38%) are designated hybrid, and 113 (or 62%) remote. This division aligns very roughly with Georgia Tech’s “Moving Forward” plan, which emphasizes a return to campus. Among remote classes, the labor is divided with equity: 62 (or 54%) of the 113 remote classes are being taught by non-tenure-track faculty, whereas 51 (or 45%) are being taught by tenure-track faculty.

Analysis of the distribution of hybrid classes, though, reveals a disparity: of the 71 hybrid classes, 61 (or 85%) are taught by non-tenure-track faculty, 5 (or 7%) are taught by tenure-track faculty, with a remaining 5 classes unassigned at the time of writing. [They were assigned to non-tenure track faculty or graduate students in the end]. These hybrid classes must include “meaningful in-person experiences” and the health risk of that experience falls primarily on us (non-tenure-track faculty), in addition to the students and the staff.

The generational differences between permanent, tenured faculty and transient, term-limited postdocs can explain some of this disparity. Georgia Tech is offering remote instruction for all employees over the age of 65. There are no postdocs in our program who qualify for that accommodation. Furthermore, Tech’s plan emphasizes “prioritiz[ing] student groups based on the benefit of their presence on campus,” which, among other things, would mean having more face-to-face first-year classes, like English 1101, given the proven benefits of first-year composition for retention.

Georgia Tech reserved other remote designations for faculty who could provide documentation attesting to their being in one of a short list of specifically defined risk categories. That list, which began with seven conditions, slightly expanded in early July, but it still does not explicitly include mental health concerns. The guidance linked above also instructs people who live with or care for others in high-risk categories to return to in-person work or take unpaid leave.

The process of applying for a remote designation was convoluted and invasive. In addition to requesting a letter from a primary care provider, HR asked employees seeking medical accommodation to fill out the five-page “Georgia Tech Covid-19 Higher Risk Alternative Work Arrangement Request Form” that, among other things, gave Georgia Tech the right to contact their health care provider directly. The transient nature of the postdoctoral faculty position makes us less likely than our more permanent colleagues to have a primary care provider in the state of Georgia; even if we do have a provider, requesting medical documentation takes time and money.

Initially it seemed that employees who wanted to teach remotely but who could not meet the above HR categories could instead work with their supervisor to find a solution. Many of us did and requested that our classes be designated “remote” for pedagogical reasons. Given our program’s focus on digital pedagogy, our supervisors have encouraged us to seek opportunities to teach remote courses. This was a possible path to safe instruction during a pandemic. We spent numerous hours developing materials for a lengthy application: a working syllabus and class schedule, plans for remote interactions with students, major assignment prompts, and sample lesson plans. Until this semester, no instructor who engaged in this process was denied the opportunity to teach remotely. However, despite our supervisors’ best efforts, that path to remote instruction was also cut off. We were all rejected without explanation.

This is not to say that we want our tenure-track colleagues marched back onto campus with us or instead of us. We have extraordinary colleagues, who study Black media, human-computer interactions, and literature, and craft award-winning poetry, stories, and games. We believe that their lives are as important as anyone’s—including our own. And to our school’s credit, they have been advocates for us, attempting to secure remote teaching for whomever felt unsafe with a return to campus. Unfortunately, their requests were denied in an attempt to preserve the freshman experience, which includes making first-year composition classes face-to-face.

“Make science based decisions.” Jeff Amy, AP Photo, 2020.

Georgia Tech is not unique in this distribution of risk. All the faculties controlled by the University System of Georgia (USG) are facing similar challenges. Likewise, a dean at Columbia University recently asked its faculty for “a more robust offering of in-person or hybrid courses,” a request that is surely going to land the hardest on the most vulnerable faculty. The University of Alabama’s college of nursing hinted that instructors with children who might not be able to teach face-to-face should communicate their “intention and ability to meet your teaching obligations” to the college and voluntarily resign if they could not meet their obligations. The college subsequently retracted that email, but again this pressure will most likely land on the most precariously employed faculty.

Our own students have demonstrated powerful leadership, collectively pressuring USG to allow all students to opt-out of in-person instruction and publicly refusing to attend in-person classes. However, safe and equitable solutions to teaching during the COVID-19 crisis require support from the tenured and tenure-track faculty that our labor protects. This open letter from tenured faculty at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill announces publicly their commitment to ignoring their school’s unsafe plan for fall instruction. Such a public stance shields their contingent colleagues who may wish to do the same thing but lack the institutional protections to do so.

Contingent and non-tenure track faculty need more shields like one created by UNC’s faculty. The method we have outlined here offers a way to track the risk and pressure placed on contingent and non-tenure track faculty, but that data is no substitute for action. We hope that universities will see the value in protecting the lives of their contingent and non-tenure track faculty. And this is a moment for tenured and tenure-track faculty to defend their colleagues with work stoppages, signed commitments not to pursue disciplinary action, and other public, coordinated acts of solidarity. Eventually, we will reach a new normal with the coronavirus. What the university looks like, who it includes, and who it defends in that future are being defined now; we can let others define it for us or start redefining it now.

We are now six weeks into our semester here at Georgia Tech. The Institute has reported a total of almost 1,000 cases and has a positivity rate of greater than 1%. While Tech’s numbers are not as bad as some others, universities are helping drive the spread of coronavirus in parts of the United States. Moreover, the situation does not appear to be improving, as noted by a colleague at Georgia Southern, given that there will not be a widely accessible vaccine for some time still. As universities start planning for the winter and spring, our call remains the same: we hope that universities will see the value in protecting the lives of their contingent and non-tenure track faculty.

A sign on a construction site for COVID-19 in Downtown State College, Pennsylvania. Goonsnick, 19 April 2020