The Little Review

(March 1918)

Modernist Journals Project

Modernism, they say, began in the magazines. Long before internet streaming and wireless television, newspapers and periodicals were the first mass media, offering authors, intellectuals, and social activists a dramatically wider domain for their artwork and ideals. These print media provided a vital outlet—and at times a much-needed sanctuary—for modernist literature in its earliest, most experimental years. If The Little Review had not taken on the risk of obscenity charges by beginning to publish Ulysses serially in 1918, if Margaret Anderson had not founded Poetry on the belief that Chicago deserved an institution for promoting verse as much as painting or opera, and if Ezra Pound had not worked tirelessly as an editor, promoter, and fundraiser for magazines to publish peers like T.S. Eliot and Hilda Doolittle, modernism as we know it today could never have taken shape.

And yet, until recent years, when students encountered this literary period in the classroom, much of the cultural work performed by modernist magazines would likely have been marginalized, if not simply forgotten. Iconic works like Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” or Eliot’s Waste Land have received continual attention, to be sure, but typically as part of the “greatest hits” approach to literature that figures like Eliot helped institutionalize–an approach given material form in anthologies, which offer us their representative canon for the age. Practical though they may be as a pedagogical choice, however, anthologies dampen our attention to the uncertainty, experiment, and eccentricity that shaped literary modernism, and to the crucial role that changes in media technology and public communication have had in the development of Anglophone literary history.

Poetry II.I (April 1912)

Modernist Journals Project

The rise of modernist periodical studies has changed the way that many of us now read and teach these landmark texts. This disciplinary movement has been held together by a clear center of gravity: the Modernist Journals Project, a joint effort launched in 1995 by Brown University and the University of Tulsa to digitize a wide range of modernist periodicals appearing from 1900 to 1922 (that annus mirabilis, often cited as a “high water” mark for the period). With ongoing support from the National Endowment from the Humanities, MJP has catalogued twenty-seven periodicals to date, all of these complete with their original advertisements, visual art, and paratextual materials, all in high-definition, with efficient (and labor-intensive) character recognition available for in-text searching.

By making this rich digital archive available, the Modernist Journals Project has expanded the pedagogical approaches that instructors such as myself can use to introduce students to the vitality and the chaos of modernist cultural production. MJP hosts a growing set of syllabi and assignments, which either directly draw upon its archive, or focus on periodical culture in general. My current English 1102 course, “From Print Culture to Digital Archive: Modern American Literature and its Periodicals,” was built around these models. As the central unit for the course, I assigned students a series of single issues drawn from the MJP. Together, my students and I looked at “In a Station of the Metro” and The Waste Land in the original volumes of Poetry and The Dial where they appeared. This meant not only appreciating these individual works in new ways (Pound’s poem a delicate minimalist ribbon closing up a series of longer, scathing poems attacking bourgeois morals; Eliot’s masterpiece without the footnotes that have come to seem an inextricable part of comprehending his allusive and elusive literary references), but also complementing these texts with attention to the commercial advertisements, visual art, and editorial opinion columns that surrounded them, creating unexpected resonances and tensions with these more famous pieces of writing. As Robert Scholes, founder of the MJP, points out, “magazine in both English and French meant ‘storehouse’ before it ever referred to printed periodicals,” and remembering this sense of collection and consumption can call our attention to the complex array of roles taken on by these literary institutions (29).

The Masses cover by Blake Daniels, Tomas Osses, Anonymous, and Anonymous

My students also examined issues that featured no “canonical” works, but which captured the cross-pollination of artistic movements that helped accelerate stylistic innovation in the modernist era. Looking over a 1912 issue of Alfred Stieglitz’s photography magazine, Camera Work, for instance, we read short “Portraits” of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse written by Gertrude Stein, which accompanied photographed visual art by these two iconic figures. In our discussion, my students and I worked to identify the productive symmetries between these three different artistic media, as well as the unique affordances distinguishing prose, painting, and photography at the turn of the century.

This unit’s culminating assignment, “Mining the Modernist Journals Project,” tasked students with selecting and exploring one magazine from the MJP, and presenting it to the class through one of its organizing values, problems, or commitments. Scaffolded with an annotated bibliography, a visual artifact, and a Question-and-Answer session following their presentation, this group project engaged the full range of written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal modes. Having been granted freedom of design, yet provided a stable archive, students pursued a range of sophisticated and engaging topics. One group examined the visual rhetoric of political cartoons in the socialist periodical The Masses, and presented their findings using the original graphic design and layout template of that magazine.

Another group explored how Harriet Monroe’s Poetry helped promote the movement known as “Imagism.” As they began research into the topic, this group discovered that Imagism was not a fixed, stable poetic category but something closer to a literary brand or label that had been used to different ends in a personal struggle between Ezra Pound and Amy Lowell. Their cleverly designed opening slide featured six other practitioners of this poetic movement all looking inwards toward these two central figures. Having followed the direction of the evidence, this group used their research into Poetry to replace the false stability of a literary “-ism” with a more historically accurate (and more dramatic) explanation of the personal alliances and animosities that were at work behind the making of modernist art.

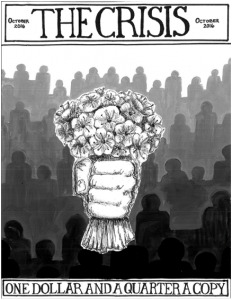

Many students chose to focus on the ways that modernist little magazines addressed issues of racial justice. Several groups looked at The Crisis, literary organ for the NAACP, and its influential founding editor, W.E.B. DuBois. Among them, one group (Yeram King, Rita Berglund, and three students who chose to remain anonymous) created a documentary-style video, which describes how DuBois used editorial commentary, advertisements for historically black colleges in the South, and photographs of accomplished members of local African-American communities to promote his vision of cultural and political equality.

Imagist authors in the Poetry circle, by Nikita Rajput, Anonymous, Anonymous, and Anonymous

Cover of The Crisis by Tyler Harper, Benjamin Zusmann, Bryce Huber, and Anonymous

Yet another group sought to imagine what the cover of a modernist Crisis might look like in 2016. In their potent final artifact, a fist tightly grips a bouquet of white Hawthorn, state flower of Missouri, before rows of faceless silhouettes, distributed in shades from black to white. These students dramatically captured the way that modernist magazines like The Crisis combined clear social critique with ambivalent design, heightening the tension between form and content so as to leave their audiences with a jarring aesthetic experience.

Whether through design practices, analysis of visual rhetoric, or close reading of poems, the Modernist Journals Project allowed my students to create artifacts that drew upon their varied talents and interests, yet which together captured the aggressively experimental spirit of the modernist moment.

Works Cited

Scholes, Robert, and Clifford Wulfman. Modernism in the Magazines: an Introduction. New Haven: Yale UP, 2010.