In my English 1102 “Digital Woolf” class at Georgia Tech this fall, we began with Howards End (1910), by Virginia Woolf’s contemporary, E. M. Forster, which we followed with Woolf’s novels, Jacob’s Room (1922), Mrs. Dalloway (1925), and To the Lighthouse (1927).[1] We will be concluding the course with her essay, A Room of One’s Own (1929). Along the way, the class viewed and blogged about the film of Michael Cunningham’s The Hours (2002), an adaptation of Mrs. Dalloway. Our focus on Woolf presents students with the opportunity to understand her imagination and complexity.

As we began reading Jacob’s Room, the students found it incomprehensible and unlike other novels that they had read. In Jacob’s Room, Woolf displaces the elements that we come to expect in a novel. She subordinates plot in favor of sensory perceptions. When Woolf published Jacob’s Room, she was dissatisfied and felt she “could have screwed Jacob up tighter if I had foreseen; but I had to make my path as I went.”[2]

The geography of Jacob’s Room provided us with an anchor for understanding it. When he defines “geography” in in World Views: Metageographies of Modernist Fiction (2012), Jon Hegglund reminds us of “its Greek roots: geography as ‘world writing.’”[3] In making their own maps of Woolf’s chapters, students were rewriting her worlds and creating visual arguments about their contents. For students, it was often the process of making their maps and grappling with Woolf’s language that was most meaningful, not necessarily the shapes that their maps took.[4] As Eric Hayot explains in On Literary Worlds (2012), “[Franco] Moretti has argued that the limitations produced by close reading prevent us from ever doing serious literary history . . . that would understand truths operating at the level of pattern as having the same epistemological legitimacy as those operating at the level of the poetry of the sentence.”[5] By contrast, mapping Jacob’s Room drew students’ attention to her sentences. As Hayot also observes, “a sentence in a novel, a word in a poem, a look, an exclamation, or a punctuation mark can become worlds if read as formal totalities of their own” (49).

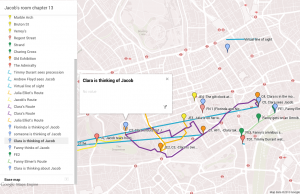

Mapping Jacob’s Room is a difficult task. Some chapters contain few locations, and even as Jacob navigates the streets of London, places are glanced at, gestured toward, or remembered. While writing the novel, Woolf also considered maps’ limitations and as the narrator concludes in chapter eight, “[t]he streets of London have their map; but our passions are uncharted.”[6] In groups, the students had a chapter or group of chapters to map for their second project. When we practiced mapping chapter five in class, the students became noticeably keener readers, attempting to determine with precision the characters’ locations. Using Google Maps, one group traced the characters’ thoughts, separating out strands indicating “Narration” and “Jacob’s imagination.” In their map of chapter thirteen, members of the same group crafted a complicated map that indicated various characters’ routes and such aspects as where characters see Jacob, imagining a “virtual line of sight,” and where they think about him.[7] This map demonstrates the complex visual and spatial dynamics at work in Woolf’s novel.

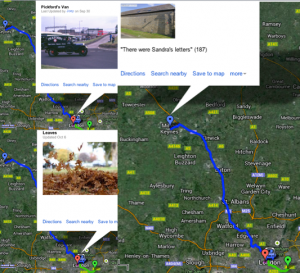

Woolf’s final chapter of Jacob’s Room occupies a single page in which Jacob’s mother and his friend Bonamy learn that Jacob has died in the First World War. One group saw the challenge of mapping this chapter as an opportunity to trace the distance that the artifacts remaining in Jacob’s room had traveled before arriving there. As the students observed in the caption accompanying their map: “unlike the protagonist in many novels, Jacob is not the center of the universe: he is, in fact, a person of small significance who accomplished little in life and died in a senseless slaughter. Woolf believes that the novel, and the lives of the characters contained therein, continues after the death of the protagonist.” Pairing Woolf’s references with such images as falling leaves outside of Jacob’s room and the location from which Clara Durrant sent her letter, the students created an image of the world that remains at the close of Woolf’s novel. The students concluded that “[t]he fact that what would typically be extremely mundane details of setting in the chapter are, in fact, incredibly important rhetorical devices, and that the bulk of his social and romantic interactions can be represented fully with four points and three lines on a map, highlight the insignificance and futility of Jacob’s life.”[8]

After completing their maps of Jacob’s Room, the students read Mrs. Dalloway and assessed existing online maps of the novel. In their blog postings, the students considered Google and Apple map platforms and the roles of these maps in their interpretations of the novel.[9] When they subsequently gave presentations of their Jacob’s Room maps, the students observed that they appreciated Woolf more after reading Mrs. Dalloway, particularly due to the novel’s organization and clearer structure.

Our focus in the last segment of the course continues to engage visual and electronic forms of communication. When we read Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the students completed blog entries analyzing passages from the novel alongside images from Leslie Stephen’s photograph album.[10] Following such scholars as Jane de Gay, the students engaged the visual landscape that shaped Woolf’s memories and the photographs that she consulted as she composed the novel.[11]

In their final projects, the students will be designing Woolf Apps for an iPhone, iPad, or computer (and potentially all three platforms or other types of products) that will enable readers to better understand Woolf’s novels. The students will not be creating the apps, but instead proposing what they would look like and how they would function. An app could, for instance, envision a scene, provide historical context, address a character, present an interpretation, create a dinner menu, dramatize a scene, guide a walking tour, or annotate a passage. The students’ apps could also engage Woolf’s language, Bloomsbury art, the sound of Woolf’s prose, recreate the spaces her characters inhabit, or shed light on allusions or historical events to which the text refers. The apps will harness such features of phones, tablets, and computers as internet capability, user contributions, access to forms of social media, use of a camera, sound, images, and gps. Each student will design a cover image for his or her app (the image for selecting it from a device) and at least two images demonstrating its features. The students could use such programs as Power Point, Prezi, Photoshop, Microsoft Word, Wix, or Weebly. Along with their images, the students will compose a 250-word rationale addressing why they designed their app as they did, how it sheds light on the experience of reading Woolf, how it would work, who would use it, and how it demonstrates “multimodal synergy.”[12]

Woolf has proved to be a productive author for digital exploration. The difficulty of her sentences alone suggests that today’s readers need motivation to devote time to them. Woolf’s visual imagination also lends itself well to teaching multimodal communication. Reading novels like To the Lighthouse, in which a painter contemplates how to depict the world, the students too begin to imagine her interpretation of her surroundings. In teaching To the Lighthouse what has become most apparent is the fact that Woolf asks such large questions about one’s impact on the world that are vital to students’ consideration of their goals early in their college careers. Digital pedagogy enables Georgia Tech students to use a medium with which they feel comfortable to begin to understand difficult literary texts that may help guide the directions that their lives take.

[1] See the conclusion of my TECHStyle posting, “Untouchable E-Books: Mulk Raj Anand, Modernism, and Technology.” http://techstyle.lmc.gatech.edu/untouchable-e-books-mulk-raj-anand-modernism-and-technolog/

[2] Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf: Volume Two: 1920-1924, ed. Anne Olivier Bell, assisted by Andrew McNeillie (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1978), 210.

[3] Jon Hegglund, World Views: Metageographies of Modernist Fiction (New York: Oxford UP, 2012), 8.

[4] See Kathryn Schulz, “What is Distant Reading?” The New York Times. June 24, 2011.

[5] Eric Hayot, On Literary Worlds (New York: Oxford UP, 2012), 18. Parenthetical citations will follow.

[6] Virginia Woolf, Jacob’s Room, ed. Mark Hussey (1922; New York: Harcourt Brace, 2008), 99. Kindle edition.

[9] The students had a choice to write about either the Mapping Mrs. Dalloway Project or the Google Map of Mrs. Dalloway’s London.

[10] Karen V. Kukil, “Leslie Stephen’s Photograph Album.” Smith College. http://www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/rarebook/exhibitions/stephen/

[11] Jane de Gay, Virginia Woolf’s Novels and the Literary Past (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006).

[12] In English 1101 and 1102, Georgia Tech undergraduates complete a series of projects engaging WOVEN (Written, Oral, Visual, Electronic, and Nonverbal) communication and addressing their interconnectedness, their “multimodal synergy.” See WOVENText. Version 2.2. Bedford/St. Martin’s Press. http://ebooks.bfwpub.com/gatech.php