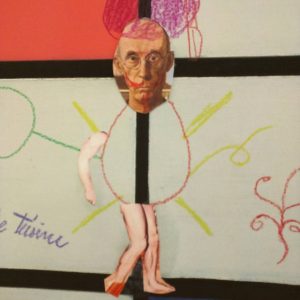

A close-up shot of a collage, created in the gallery space from copies of iconic artwork. (Courtesy of Eric Rettberg.)

In July 2015, The Chronicle of Higher Education ran an article entitled “Final Exams or Epic Finales.” In it, Anthony Crider, an associate professor of Physics at Elon University, describes how and why he ends his courses not with exams, but with “epic finales.” These epic finales can take many shapes: students may, for example, create their own post-apocalyptic society in a course about dystopian literature. Crider argues that these assignments can help instructors give students the same kinds of awe-inspiring experiences that drew them to their discipline in the first place, and show them that the end of a course does not have to be the end of learning. Although I end the semester with a final portfolio, I work to incorporate the spirit of the epic finale into my courses.

Around the same time I read Crider’s essay, I was wrapping up a summer working at the North Carolina Governor’s School, where high school students in the art program put on an interactive and surprising gallery presentation of their work. Pieces included a life-sized sculpture of a woman cleaning, designed to remind audiences of the often-unacknowledged people who kept the gallery space clean, and a performance piece in which a student who looked like the Greendale Human Being was covered in objects collected from students. As the student walked a runway, others pulled these objects off of her one by one. Guided by their instructor, Luca Molnar, the students had clearly spent a great deal of time preparing to speak with audience members about their inspirations, their methods, and the meanings of their artworks.

I hoped to replicate this experience in my English 1102 class. The course, which focused on the theme of multimodal communication in avant-garde literature and art, asked students to create an original piece of avant-garde artwork, write an accompanying artist’s statement, and present their work in a gallery opening. In this celebratory presentation format, students set up their work in the classroom gallery and spoke informally with audience members about their creative process, inspiration, and conceptual framework. I split the class into two groups and over the course of two class meetings half the students presented their work while the other half walked through the gallery, examining different works in any order they chose. By replicating a real-world gallery opening as closely as possible (though I replaced the wine and cheese with cookies from Trader Joe’s), I challenged students to hone nonverbal and oral communication skills by discussing their work in an impromptu, conversational manner. These gallery presentations felt like an “epic finale,” but they also encouraged students to plan for communicating in unpredictable rhetorical situations and to take aesthetic and conceptual risks.

Performance artist Yoko Ono became a model for my students as they worked to understand multimodal synergy and the relationship between creator and audience. In her Cut Piece, Ono moves as little as possible while audience members cut off small bits of her clothing. My students were fascinated to see how this seemingly simple performance piece engages visual and nonverbal communication in order to reflect on gender, sexuality, violence, and vulnerability.

Nevika Shah’s artwork, “Classy Never Trashy,” uses a mix of materials that signify, and comment on, college life.

My students created projects that activated many of the same experiences of surprise, disorientation, and delight that they saw in viewers of Cut Piece. Students, for example, waited patiently in line to flip a coin that determined which of two covered paintings they would be allowed to look at. They followed the artist’s command to stay silent about the features of the work they were allowed to see. It was an exercise in chance, curiosity, and a little gentle trolling. Another student enlisted her friend to serve as a silent model, wearing the dress she constructed from red solo cups, condom wrappers, and old issues of the Technique. Although the model remained silent, the artist spoke eloquently about how the materials of the dress signified a campus culture that simultaneously celebrated and shamed female students for their sexual desires. Students altered possessions that they treasured–a skateboard and a favorite shirt–to create a form of self-portraiture. Many of the students’ artworks were created in the gallery space as, for example, students cut up prints of iconic artworks and attached them to a canvas to create a new piece. While I wouldn’t exactly say that Hall 106 was transformed into the Cabaret Voltaire, a sense of camaraderie, play, and engagement pervaded the classroom.

In her 2009 essay,“Negotiating Rhetorical, Material, Methodological, and Technological Difference,” Jody Shipka explains that when multimodal assignments incorporate audience interaction, they also encourage greater engagement for students who create these artifacts (2009, W345). By focusing specifically on audience interaction in this assignment, I encouraged students to make rhetorical choices based on how they wanted audiences to respond. Students were just as likely to be intimidated as excited when they realized they could create nearly any multimodal artifact they wanted. I started to sound like a broken record when they asked me what they should make: “these decisions are the point of the assignment. Any rhetorical choice you make will produce different effects in audiences.” The gallery presentation created a kind of dual rhetorical situation in which students could work to shock, delight, or disorient their audience with their artwork, then clarify and contextualize that work.

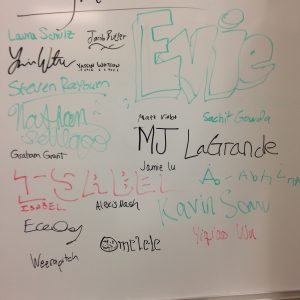

Student signatures on the gallery wall.

To prepare for the gallery presentation, students participated in a workshop where they practiced answering–and asking–questions about their work. With a small group, students took turns answering questions I drafted. My questions were necessarily a bit broad–Why did you make this piece? What other artists influenced you?–and occasionally a bit goofy–I’m confused; what is your piece? (I endured light mockery during this particular workshop.) If I were to conduct this assignment again, I would also ask students to write their own questions about the work of their peers.

In their final portfolios, many students claimed that this assignment reignited a creative energy they had long ago discarded. When creating the artworks, students must articulate a complex concept or idea through a multimodal project that is finely attuned to the rhetorical situation of the gallery or museum space, with its mood of contemplative seriousness and hushed reverence. In the gallery presentation, they must respond nimbly to questions about their creative process and rhetorical choices. While students nibble cookies and wander from piece to piece, they practice asking relevant questions. While they stand by their original artwork and speak with their colleagues about their process and their intention, students practice owning their ideas and listening to the people with whom they are communicating. In the gallery space, as in the world outside it, communication not a static transferral of information, but a constantly shifting exchange.

Works Cited

Shipka, Jody. “Negotiating Rhetorical, Material, Methodological, and Technological Difference.” College Composition and Communication 61.1 (September 2009). 343-366. NCTE. Web.