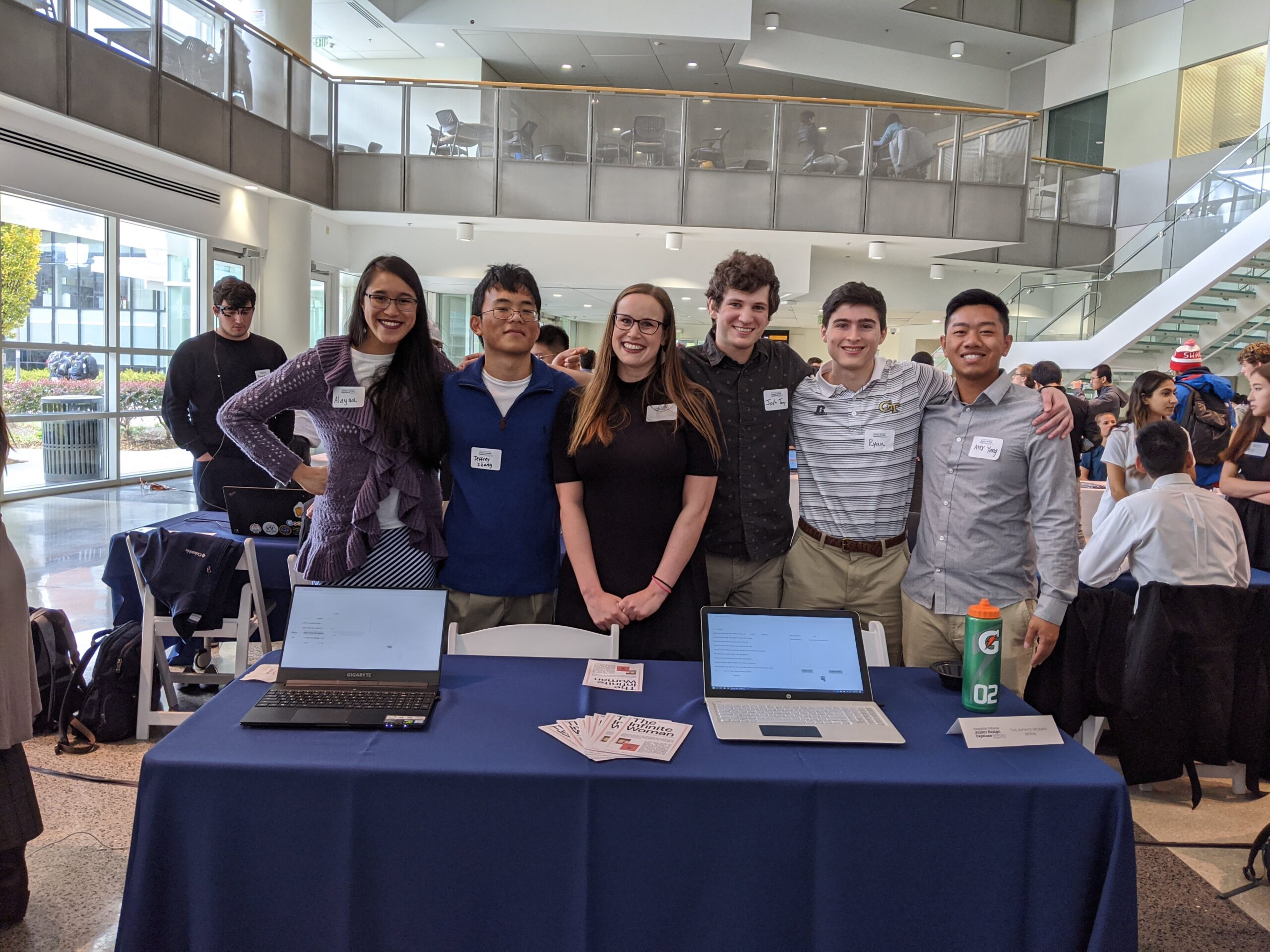

The team and I (L-R: Alayna Panlilio, Jeffrey Zhang, Katie Schaag, Josh Terry, Ryan Power, Alex Yang) celebrate our successful developer-client collaboration as they present the final project at Georgia Tech’s Junior Design Capstone Expo in December 2019.

Introduction

The Infinite Woman is an interactive poetry platform that computationally performs contemporary poetic techniques of remix and erasure. As a feminist critique and artistic intervention, it remixes excerpts from Edison Marshall’s novel The Infinite Woman (1950) and Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex (1949). An n-gram algorithm procedurally generates infinitely scrolling sentences that attempt to describe and critique an eternal feminine essence. Users can select sentences from the infinitely scrolling text to send to a blank workspace, where they can erase words and rearrange sentences to create their own poems. Meanwhile, fog slowly erases the screen. The web application is hosted at theinfinitewoman.com, and should be compatible with all devices and all internet browsers (except Safari). It was selected by the Electronic Literature Organization for inclusion in the 2020 virtual exhibition (un)continuity. You can view a demo video here.

With my creative direction, the cross-platform web application was designed and implemented in 2019 by a team of Georgia Tech computer science and computational media students: Alayna Panlilio, Ryan Power, Josh Terry, Alex Yang, and Jeffrey Zhang. The development process took place in a unique context: Junior Design, a two-semester CS/LMC capstone course for computer science and computational media majors to build custom software for a client. Most Junior Design projects are purely practical—a course management system, a data visualization tool, a nutrition tracker—so proposing an experimental creative writing or visual art project was unusual. Every step of the way, we aligned each technical and aesthetic aspect of the platform with the overarching concept, synthesizing the humanist and computational spheres. For a detailed look at the students’ implementation process, view their coding sprint demo videos here, here, and here.

In September 2019, as the team was transitioning from the design phase to the implementation phase, I interviewed them about their thoughts on the computational dimensions of poetry, authorship, gender, and language. This fun, wide-ranging conversation with a brilliant group of students addresses everything from chance operations to biased algorithms to poetic structure to hacktivism to UX to aesthetics.

In the first part of the transcript, published here, the team and I discuss creative coding: computational approaches to experimental poetic techniques, the syntax of coding and poetry, literalism vs. metaphor, and the tension between functionality and creative expression—reading the lines vs. reading between the lines.

The second part of the transcript, published here, focuses on the team’s engagement with feminist computational poetics and experimental user interface design. We address topics such as collaborative authorship, gendered algorithms, and the role of scripts, random probabilities, and errors in procedurally generated writing.

This third and final installment (edited for length and clarity) illuminates the project’s transdisciplinary collaborative development process.

Transdisciplinarity

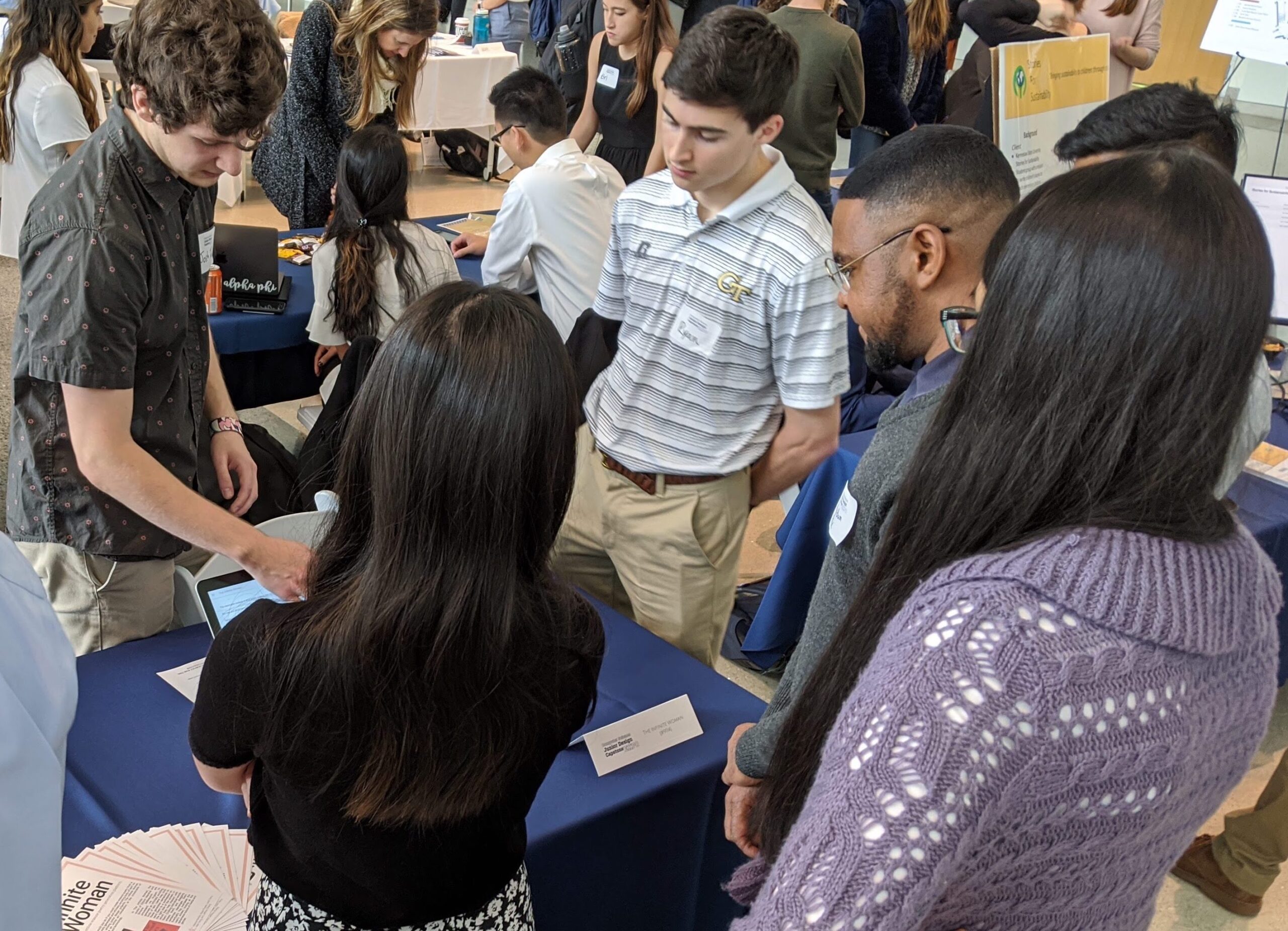

Alayna Panlilio guides a student through interacting with the web app, while Josh Terry discusses the project with Serve-Learn-Sustain Service Learning & Partnerships Specialist Ruthie Yow.

How would you describe the relationship between computer science and computational media? Where do they converge and diverge? In our project, where do you see this dynamic between computer science and computational media playing out?

JOSH: Within CS and CM, computer science and computational media, I think they converge in that they both involve coding. They’re creating digital applications for people to use on devices that are pretty pervasive in the world around them. Where do they diverge? It’s tough because some people would say computational media is more people-focused, but I would argue against that, because within the computer science program at Georgia Tech we have a thread, a part of the program that’s half of your major, called “People.” So you’re building interfaces that are meant to be used by people and programs while keeping the people using them in mind. It’s a lot of psychology and so on. But where computational media differs from that is rather than keeping the functionality of the code in mind, as far as people go, you’re keeping the appearance and the design and the usability in mind. So while those are both geared toward people, computational media is more about making a thing—I want to say fun to use or satisfying to use.

Is it also making a thing beautiful?

JOSH: It’s making a thing beautiful. It’s trying to make an interface pretty. What do you all think?

RYAN: So, I’m not a CM major, but I do have a concentration in Media for CS. I can tell you that all my media classes have been front-end based. Those are the only classes that have been front-end based. So there’s a huge emphasis on user interface, and what you code is actually what you see on the screen. None of the other classes are really like that. A lot of it’s just working in the back-end and getting something to actually work. That’s something I really like about media. And that’s a big difference between typical CS classes, back-end vs. front-end.

JOSH: What’s interesting about this project is that it’s almost all front-end. Almost. The only thing that isn’t is maybe some of the functionality under the hood of how the infinite scroller works, how the canvas will work, and how the n-gram’s probabilities will play out. Everything else is front-end. The front end is what you use to interface the code with the person, essentially. And so while the computer science “People” thread is geared toward keeping people in mind and how their brains work while you code, computational media is geared toward interfacing that code with people.

Do you have any thoughts on the relationship between computational media and digital humanities scholarship?

JOSH: Yes. A lot of the courses that I’ve taken through the College of Liberal Arts have involved digital humanities. So Culture and Communication, which I took with Josh Fisher, focused on the implications of virtual reality in society and the impacts of technology becoming ever-present in society. Such as “What are the impacts of the WeChat app in China?” and similar things. And I had considered doing grad school in the Digital Media program. So they’re very, very closely intertwined.

How do you conceptualize the UX component of the project?

JOSH: Keeping it intuitive. That’s what we’re trying to do. Intuition is a really cool thing, and design heuristics, which we’ve done plenty of discussion about in the first semester, are all really important. But we’ve done our research and we think we have a good design.

ALAYNA: Something that we talked about in one of our last big group meetings with our professors is that our project is different from a lot of other projects, in that there are specific things that we want to do that kind of go against what some of the design heuristics were wanting us to do. But once we had changed the definition of this project to an art installation, it gave us a little bit more freedom to do what we want: to make the application and change some of the design heuristics to better fit what it is that we want to do.

Could your team write a heuristic guide for people who are making more artistic projects?

JOSH: To an extent. So as far as design heuristics go, they’re great to follow and they’re great to keep in mind, but when you’re making a program that you want to be usable by people, you don’t necessarily want to follow the design heuristic so much as you want to understand it and be able to explain why your application does or does not line up with it. So if you have a good rationale for not aligning with a design heuristic, such as our infinite scroller deliberately taking some amount of control away from the user, then that’s okay.

Collaborative Development Process

The team presents The Infinite Woman web app at Georgia Tech’s Junior Design Capstone Expo in December 2019.

What is your collaborative process like? How has the project evolved over the past several months, throughout your meetings with me and with each other?

RYAN: It’s good. I feel like our first sprint went really well. I was initially the only one familiar with Angular and Ionic, which are the frameworks we’re using. But I know Jeffrey works really well with it. Like, he just looked online and found explanations, just as an example. Just because you’re not familiar with something doesn’t mean you can’t learn it. So I feel like we’ve collaborated really well. I’m pretty happy with the first sprint results.

ALAYNA: Just going from not knowing what Angular and TypeScript and Ionic were, to being able to actually look at the code and understand what parts of it are making what show up and how all of the three different files interact, that was just kind of like, okay, cool. It works. I can understand this now. Cool.

JOSH: One of our first meetings this semester, we talked about who’s most comfortable with different aspects of programming. So who’s most familiar with these existing platforms we’re using, who’s most familiar with back-end, front-end, UX, and so on. And so our tasks this semester have largely been geared toward keeping people maybe not in their comfort zones but doing things they’re more familiar with just to be more efficient with our project.

How did the process of making your Part 1 deliverables (vision statement, prototype, UX report, video narrative, etc.) impact your approach to the project? You already talked about this a little bit with the heuristic evaluation. Any other thoughts on how that process impacted what you’re doing now?

RYAN: The prototype impacted it. I had a little image of our prototype pulled up when I was initially making the application, so I just followed it.

ALAYNA: We had to go back and change the initial client charter and things like that. Even though we had to reorder our sprint goals, having those things available to us, having a general idea of what we’re going to do—maybe not necessarily the order that we’re going to do it yet, but just having that available—made it a lot easier to figure out what we’re actually going to do for the semester.

What technical information would be useful for me to know as I keep thinking through the project’s meaning and implications?

JOSH: As we do create more and more of the project, the work that we’ve done becomes more solidified, and future work is based on that previous work. So going back and making changes to those can have rippling changes through the rest of what we’ve done. Going back a long way is really difficult as far as making changes goes. So while we are able to make some changes, the farther we get in the semester, the less modifiable it becomes.

Okay. I promise not to ask for anything else. [laughter] I love it as it is. It’s perfect.

RYAN: It’s fine.

JOSH: It’s great.

RYAN: We can do it.

Any other free-form thoughts or reflections about your work on the project?

RYAN: It’s going well. We’re doing it [laughter].

JOSH: I think it’s really cool how different this one is from so many of the other Junior Design projects. Many others are like, “Okay. You’re making an explicit, solution-driven thing to help X business do Y task.” And we’re doing a very abstract, really fun, cool, interesting thing to hopefully help someone smile. Right? Someone will stumble upon this and think it’s a cool thing. And we’ll make their day a little bit better. And that’s really cool to me.

That’s awesome.

ALAYNA: I think since ours wasn’t as cut-and-dried of a project—usually when we’d get assignments from class, we’d have mostly all of the steps that we’d need. And a lot of the more cut-and-dried applications already had what their specifications were. Sometimes we’d get the platform they wanted to use and things like that, whereas with this project we were able to—even though it was sometimes a little bit just going back and forth—a little frustrating trying to figure out, “What is it that we’re trying to do here?” We kind of made our own project out of it, if that makes sense.

Cool. So you were able to be creative in figuring out what you wanted to do?

ALAYNA: Mm-hmm.

Great. And as developers, was it frustrating or nice that I kept asking for your feedback, rather than saying, “Do this. I don’t care about having a conversation”? Or was that annoying because you felt like I was a client who didn’t know what I wanted? You can be honest. I know I’m an annoying client. [laughter]

RYAN: Moderation is key to any successful project, I feel. So knowing what we’re doing and having all six of us on the same page is hugely important. We do appreciate what you’re doing.

Awesome.

ALAYNA: Yeah. I think it’s more that we were frustrated with you because we were trying to also help you figure out what it is that you wanted [laughter].

Totally. Yes.

JOSH: I think it’s cool seeing how different people from different backgrounds work together on similar things. So we have someone with a very artistic or free-form literature, media, communication background meeting the computer science background. It’s real interesting seeing how those work together. I think it’s good to have that broad array of work styles.

RYAN: They almost seem like opposite ends of the spectrum though, honestly. And that’s pretty cool to combine them.

Awesome. Well, thank you, guys, so much because I thought the idea that I had was simple. But then the more you were actually doing and presenting specific things, the more I was like, “Oh, wait. I haven’t considered that. What is that? Ahhh.” [laughter] So I have really appreciated the process. And this conversation was immensely helpful. This was just the best brain think tank. Thank you so, so, so much.

RYAN: Of course.

Y’all are brilliant. Thank you.

ALEX: Thanks.