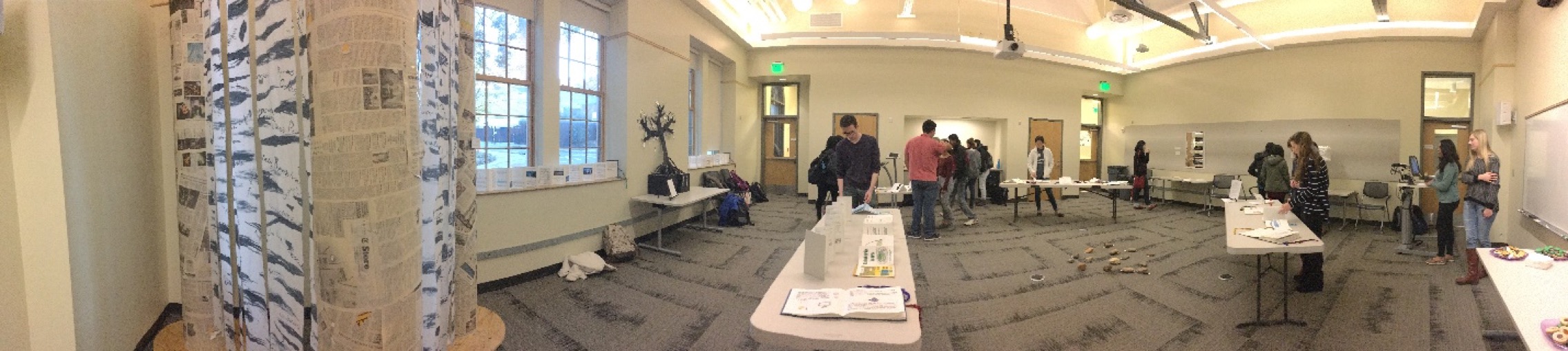

The gallery opening and book release reception in the Stephen C. Hall Building on December 1, 2016

Last fall, I led students through a writing and communication course titled “One World is Not Enough.” This class investigated cultural values and ideologies as exhibited in the narratives that societies construct and consume. The course focused on two contemporary novels, Stephen Graham Jones’s Ledfeather and Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, and we also read and critiqued a variety of children’s stories that take on topics related to sustainability more directly, such as Ada Twist, Scientist and Shel Silverstein’s classic, The Giving Tree. Although we were primarily exploring the narrative form, a key pedagogical component of my course was the utilization of non-narrative forms of expression––poetry, visual art, and graphic design––to deepen critical and creative thinking about the subjects we explored in class. While students read fiction, they formed initial responses through the creation of poetry and visual art, using these non-narrative modes to disorient habitual reading and writing patterns and stimulate students’ awareness of themselves as critical consumers of culture. These creative acts of translation also prepared my students for the creative task of writing and designing their own children’s books in collaboration with the students of a local elementary school in Atlanta’s Kirkwood neighborhood, and in the preparation and installation of an art exhibition for the Georgia Tech campus.

Thanks to grant support from Poetry@Tech, Serve-Learn-Sustain, and the GT-Fire Embedded Artist Project, I had the resources to incorporate art installation, poetry performance on film, and children’s book production assignments into the course. With the guidance of a storyteller, sculptor, and bookmaking artist, my students became poets, authors, and artists while examining the power of rhetoric in a variety of forms, all concerned with the environmental and socio-economic narratives our society constructs. This essay explores two of these initiatives, reflecting on the value of teaching poetry and visual art in the writing classroom.

The Poetry@Tech Project

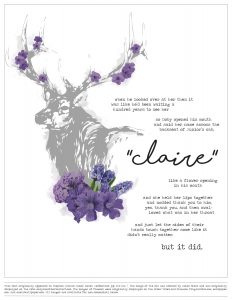

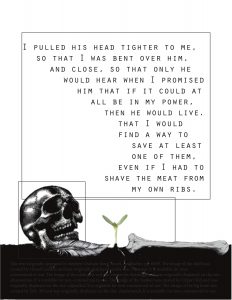

I believe that imagination is essential, not antithetical, to critical analysis. Through poetry writing exercises in my course, I hoped to create a spatial intimacy between my students and the novels they read, letting them experience the critical challenges of creative construction first-hand. My first poetry assignment was an exploration of character in Kafka on the Shore. Rather than asking students to journal critically about Kafka, the suppressed, runaway protagonist of the novel, I required them to explore his motivations and desires through the composition of a poem written in his voice. Through their writing, students gave expression to Kafka’s fears and dreams, based on his actions in the novel. This exercise led to a reverse-analysis of their poetic choices and the character’s driving desire, stimulating a critical discussion of the novel’s structure in relation to the protagonist’s will. A byproduct of this assignment was deeper investment in the story; by channeling the character, my students gained empathy for him despite his morally questionable choices and behavior. This character exercise served as preparation for the formal challenges of Stephen Graham Jones’s novel, Ledfeather, a non-linear novel told through myriad, often nameless, character perspectives. Students used the shifting voices of Ledfeather as maps to plot development. Each student then created a literary broadside spotlighting a key theme from the novel through a metaphorical interpretation of one character’s voiced reflection. Transforming the novel’s language into visual poetry served as a bridge toward understanding metaphor’s role in the narrative. This project also highlighted the significance of perspective in the creation of community narratives.

Extending this idea into our own community consciousness, I generated a Poetry@Tech assignment that reflected poetry’s power to engage in critical environmental, social, and economic issues facing our world today. Poetry translates our cultural narratives into song. Students explored this idea in a video performance designed to showcase their development of multimodal communication skills and strategies over the course of the semester. In each video, students also demonstrated individual understanding of sustainability issues and a deeper awareness of poetry’s role in social narratives. The four prompts were:

- write and perform a critique of one of the Poetry@Tech readings using the Writing and Communication Program model of WOVEN (written, oral, visual, electronic, and nonverbal communication)

- perform and analyze a poem written by one of the Poetry@Tech poets

- choose a poem from the socially-conscious website, Split This Rock, to perform and analyze

- write and perform an original poem that explores sustainability issues or the inherent poetry found within another field of study on Tech’s campus

Because the students created videos at the beginning of the semester reflecting on their relative strengths and weaknesses in WOVEN communication, they used the benchmark as a chance to demonstrate increased proficiency in the medium. The assignment’s best performances reflected awareness of individual strengths while utilizing a blend of creative and critical delivery of the poet or poem explored.

The Embedded Artist Project

My course was also part of a pilot research project sponsored by a GT Fire Grant: the “Embedded Artist” program. This project was designed to explore the role of the arts in fostering multimodal literacy and creative thinking, particularly for STEM-oriented students. For my course, I partnered with former scientist, local sculptor, installation artist, and Associate Professor in the Ernest G. Welch School of Art & Design at Georgia State University, Ruth Stanford. Together, we designed an assignment and assessment plan for my honors section of the course. Our challenge was to design a visual literacy lesson that highlighted Stanford’s expertise and aligned with the intellectual goals of English 1102.

A central component of my course was the writing and creation of handbound children’s books in collaboration with the students of Toomer Elementary School. Each team-generated book explored one aspect of sustainability as it relates to the Atlanta community. Because each team would invest months of research and creative energy into its chosen sustainability topic, Stanford and I opted to craft an art assignment that extended this process, allowing students to creatively and critically translate their sustainability narratives into a predominately visual medium with a markedly different audience in mind. This final translation exercise afforded the opportunity to bring the sustainability conversation to peers and colleagues on Georgia Tech’s campus.

Artwork by Matthew Wallace, Laura Meyer, and an anonymous student

In preparation for the assignment, Stanford visited my class, delivering a presentation on her multimodal art installations. Later in the semester she returned, leading a brainstorming workshop with individual groups in the gallery space. At this point in the semester, the teams had generated the stories and were in the final stages of book production. Stanford sat down with each team, discussed its topic, and listened to student ideas about how such topics might translate from children to adults, narrative to visual art. A key challenge was finding the right metaphor. For example, one team struggled with its topic, water usage on Tech campus. Realizing that water was an unstable property to exhibit in the gallery space of the Stephen C. Hall Building, Stanford encouraged the students to find a quantifiable image that a Tech audience could relate to the topic of water. The team decided to use the plastic water bottle, creating a three-dimensional map of the Georgia Tech campus, and highlighting buildings on campus with greatest water consumption.

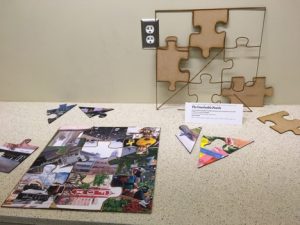

Artwork by Elizabeth Dworkin, Tanya Sharma, and Sukanya Basu

Another team’s children’s book tackled issues of cultural stereotyping. The children’s story was intergalactic in theme, but their visual project honed in on intercultural microaggressions taking place on and around Georgia Tech’s campus. After meeting with staff from Georgia Tech’s Office of Institute Diversity and gathering first-hand accounts of racist verbal attacks, the team designed an interactive work that consisted solely of language and rocks. During the reception, a pile of large rocks were placed on the floor; attached to the underside of each rock was a first-hand account of verbal attacks fueled by racism. It was only by picking up the rock, turning it over and reading these raw, emotional stories that a person could feel, literally and figuratively, the weight of racial and cultural violence. Through this collaboration with Stanford, my students learned that art was not mere recreation of the world by skillful drawing and painting, but that art reflects a means to re-examine our views of the world through introspection. Stanford broadened students’ perceptions of art by showing them that artists don’t necessarily rely on recreative talent. She enforced the idea that art is a form of communication––that it is researched, planned, drafted, and that art, like writing, is an opportunity for analysis and reflection on the world around us. This empowered my students to create in non-traditional modes such as sculpture, puzzle design, and collage.

Specifically, the honors section was composed of six teams of three students each, and six team-generated art pieces were installed along with the eighteen children’s books for a gallery event/book release reception on December 1. The art projects involved a range of topics: Georgia Tech water use, student well-being and balance, the relationship between Georgia Tech and Atlanta’s Westside community, racist language, deforestation, and the challenges of integrating social, economic, and environmental sustainability issues at Georgia Tech and in the city of Atlanta. Students from all three sections attended the art opening, so everyone engaged with the artwork as creators, viewers, and critics. It was a pleasure watching my student-artists actively discuss their work with peers invested in the topic.

Lessons Learned

Working with poetry and visual art last semester was a rewarding and surprising way to incorporate WOVEN skills into my classroom. It was surprising how willing and eager my students were to compose their own poetry and to create works of art. Their children’s books were unique and engaging. I credit the collaborations I had with a storytelling expert, a book binder, and a visual artist for the success of this project. These partnerships stimulated my students and held their focus at all stages of the process. My collaboration with Stanford was particularly successful for a few key reasons. First, as a professor of art at GSU, she understands the issues that teachers face in assessing visual literacy. She came to the project understanding the need for clear assessment parameters along with the limitations first-year writing students face practicing art for perhaps the first time. The fact that she was formerly a scientist also gave her unique credibility with my students. And the value of having an expert physically present in the classroom was also a luxury. Stanford’s availability set the tone of the semester, and she volunteered to speak to my students on the second day of class. Finally, the collaboration succeeded because Stanford specifically intended to design an assignment that progressed from my original bookmaking task; forming a collaborative project as a generic translation of another was a brilliant strategy. My students gained an experiential appreciation of rhetoric through the retooling of a children’s book to an adult art installation. This translation assignment was also essential in keeping student assignments manageable in the course.

It was a demanding, challenging semester. One might look back on “One World is not Enough” and declare, “one semester is not enough.” Sustainability’s composite issues were navigated through broadside and book jacket design, children’s literature, contemporary novels, poetry, the visual arts, and a book reception/art opening. Thanks to the generous support of on and off-campus partnerships in the form of grants, co-teachers, and community collaborators, however, the course successfully and appropriately enacted the necessity of and challenges inherent in weaving multiple perspectives and media in the telling of any story. By the semester’s end, many students expressed appreciation for the fact that sustainability means more than environmental consciousness, and they have greater understanding of the complex issues we face in navigating a globalized future because of it.