Jenny Holzer’s “Inflammatory Essays,” as displayed at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona. Photograph by Damian Entwhistle used via a Creative Commons license. Original image available at this link.

Before coming to Georgia Tech, my approach to teaching writing and communication through fictional work could be summed up like this: students will learn how to analyze novels and short stories and then write arguments explaining their analysis. They will support those arguments by close reading passages and quoting academic articles they find on JSTOR or Project MUSE. Sound familiar?

This semester, I tried a different approach in my English 1102 class, “What is an Avant-garde?” Instead of treating fictional works mainly as objects of study to which we could apply our critical thinking and argumentative writing skills, those works became models for multimodal communication. In this post, I want to outline a strategy for treating literature as a model of multimodal communication, and not just an object about which to make arguments. Avant-garde literature and art, which often seeks to bewilder or alienate audiences, to collapse the distinction between art and life, and to break the rules of representing the world, defamiliarizes everyday communication, offering a perfect opportunity to examine the relationship between meaning (what you say) and rhetorical choices (how you say it).

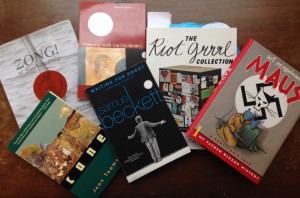

The course adopts an expansive view of the avant-garde and includes texts by figures including M. Nourbese Philip, Jean Toomer, Art Spiegelman, Samuel Beckett, and Harryette Mullen.

The predominant mood in my classroom, at least for the first half of the semester, has been confusion. Slowly but surely, students have become more comfortable being confused, and their initial bewilderment at the nonsense of Dada or the pointlessness of Waiting for Godot has helped them analyze the more accessible works, like Maus and the documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop, that have come later in the semester. In order to make works like the Futurist manifesto or Riot Grrrl zines approachable for my students, I departed from conventional academic notions of the avant-garde and framed our readings in terms of the unwritten rules of artistic and literary communication. Throughout the semester, we’ve approached our readings by talking about how they break those rules.

During class discussions of the course readings, I frame frustrating or confusing characteristics of a work in terms of communication rules audiences expect. With Beckett and Stein, I ask, “what’s missing? What do you need in order to make sense of this work?” Students come up with lists that include conventional aspects of literary analysis, such as plot, character development, conflict, perspective, and context. Then, we talk about why these these characteristics enable writers to get ideas across with language. Specific actors in the subject position of a sentence tell you who is doing what. A cohesive point-of-view limits what audiences see, but it also enables them to see anything at all.

This strategy opens up conversations about how structure can enable or occlude understanding, but it also offers a concrete object through which to explore abstract concepts. A discussion of the “Roast Beef” section of Tender Buttons approaches the question of how writers make meaning by offering a crash course in introductory semiotics. Starting with the beat poet Lew Welch’s reading of Tender Buttons, in which he explains how Stein forces readers to see each word as a sign, rather than the referent it points to, I ask students to think about the relationship between a word and its meaning. We talk about all the possible meanings of, say, “tender,” and then map out specific ways a given sentence refuses to signal the “correct” meaning. By shifting away from a reading mode that seeks to unearth the stable meaning behind the words, we can begin to talk about how language makes sense at the sentence level, and we can think about more quotidian gaps between sign and meaning.

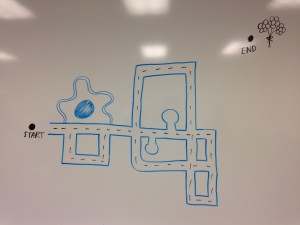

A student enacts “Map Piece” by Yoko Ono, which instructs the reader to “Draw an imaginary map” then modify it according to a series of instructions. The instructions for “Map Piece” can be found at this link.

When a text resists interpretation, it also invites reflection on the particular mechanics through which language and other sign systems make meaning, and it encourages audiences to attend to the rhetorical situation in which they find the text. Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays offer us an opportunity to describe how context shapes audience reception. We look at her posters collected in the gallery space, then talk about what it might have been like to encounter a solitary essay while walking down the street in New York in 1980. Collecting the pieces on the gallery wall, students say, emphasizes the contradictions between each essay and enables audiences to recognize her implicit claim that all extremists sound the same. At the end of this conversation, we link Holzer’s relationship with her audiences to the rhetorical situation of students’ projects. Where will audiences encounter the students’ manifestos? What can they know about their audiences, and how can they aid (or obscure) audience understanding?

Avant-garde works don’t just encourage reflection on the relationship between artist and audience; they also make complex arguments that help students analyze the relationship between form and content. Experimental works announce their rhetorical choices in a way that’s quickly recognizable to students. M. Nourbese Philip’s Zong! (Wesleyan, 2008), for example, is a poetry collection composed entirely of language taken from an eighteenth-century court case, Gregson v. Gilbert. The case revolves around a lawsuit brought by the owners of a British slave ship against their insurance company, who refused to reimburse them for losses from a 1781 transatlantic journey. The ship was carrying 470 enslaved people from West Africa to Jamaica, and after veering off course, many of the people died from lack of food and water. The ship’s captain, believing that insurance might kick in to cover the cost of the lost cargo, but not if the people die from “natural causes,” had the 150 remaining enslaved people thrown overboard. By breaking the language of the law open into the screams of the murdered people, Philip seeks “to not tell the story that must be told” (189). She does so with poems that look like letters scattered haphazardly across the page, a visual feature that calls to mind the “throwing overboard” she seeks to condemn and mourn (15). In Zong! #1, what looks like a random collection of w’s, a’s, and g’s takes shape as the drowning cry of “water was our water good” when we hear Philip read from the collection. We can then talk about the affordances of multimodal communication–that is, what giving voice to a poem can do to engage audiences and make claims–even as we consider the limitations of language for articulating suffering.

As I write, my students are completing their own avant-garde projects, which they will present to their peers in a “gallery opening” this week. Some of them are following in John Cage’s footsteps and leaving much of their final artifact to be determined by their audience. Others have coded apps that create poems, or made websites that encourage audience interaction. These projects may seem like idiosyncratic larks, but they employ the complex rhetorical skills we’ve been studying all semester: understanding the assumptions and beliefs of your audience, deciding how you want them to respond, taking advantage of WOVEN modes of communication, and seeing representation itself as a set of choices with aesthetic and ethical consequences.