Figure 1: The homepage of an English 1102 Perusall website

By Kendra Slayton

As a medievalist, I have always felt moved by Chaucer’s optimism in the General Prologue of the Canterbury Tales when he describes how into a inn came “nyne and twenty in a compaignye / Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle / In felaweship” (“nine and twenty in a company of various folk, fallen together in fellowship by chance,” 24–26). As a composition instructor, I’ve also felt that this parallels the start of the semester—in every classroom, roughly twenty five or so students and their teacher come together, sometimes with nothing more in common than the conveniences of scheduling. The question thus becomes—how do we work to form fellowships of learners in our classrooms, even if many of our students are there not because they feel drawn to the section’s topic but because the section meets at a convenient time? In the case of Georgia Tech, teaching a composition course with literary themes to STEM students can already be a challenge, particularly when it comes to eliciting discussion that delves beyond the surface-level of the texts; including medieval themes in such a course even more so; teaching said course entirely online, with “Zoom fatigue” already increasing the odds that students will (understandably) be avoiding audio/video and even chat participation? Let’s just say that preparing for such a course is high on the list of things that can cause a teacher a bad bout of imposter syndrome.

Nevertheless, hopelessly confident in the value of studying medieval literature, I persisted. In both Fall 2020 and Spring 2021, I taught an English 1102 course with the theme, “Storytelling and Society: Genres of Medieval British Literature.” I taught my classes with an even mix of synchronous and asynchronous days. Students who couldn’t make the synchronous sessions were also given the option to take the course completely asynchronously. When planning this class, I quickly realized that I needed a way to maintain a sense of continuity between the synchronous and asynchronous days and a way for students to stay in touch with each other (and me) even if they could not attend live class meetings. Perusall, a free online annotation tool, offers a way to bridge synchronous and asynchronous learning activities as well as many other affordances ideal in a remote-learning setting. This article documents my discovery and use of Perusall, a tool that I will continue using long after returning to face-to-face teaching, and the ways it has profoundly improved my pedagogy; student engagement; and the quality of both synchronous and asynchronous class discussions.

Figure 2: Perusall company homepage

I first learned about Perusall from my colleague, Dr. Mimi Ensley, as we were talking during summer 2020 about our online course design for the upcoming Fall semester. One of the most attractive points about Perusall is that it is free and easy to integrate with an learning management system like Canvas. Teachers upload course readings as .pdf or .doc files. Students then annotate the document by highlighting text and adding comments, which everyone else in the class can view. Perusall automatically groups comments on the same phrases into a thread, and students (and teachers) can directly reply to others using the @ symbol. Hashtags can also be added to comments. When students find a comment useful, they can upvote it, and teachers can also star comments to save for later. In my own class, I ask students to write at least 4 annotations for every reading: 1 question or point for further discussion, so as to encourage students to follow their curiosity and to generate conversation-starters for discussions on synchronous course days; 1 favorite quotation (using the hashtag #favquote) with a brief explanation as to why it appeals to them, so as to increase personal connection to the texts; and at least 2 other annotations of any kind.

I began the semester by having my students complete some “MythBusters”-style readings. One such piece, by Dr. Eleanor Janega of the London School of Economics, is “I Assure You, Medieval People Bathed,” which discusses everything from the medieval soap trade to bathhouse guild regulations. I was certain that in a traditional in-person course, the piece would spark animated discussion. Janega’s article is one of the most delightful examples of public-facing scholarship I’ve come across, not only because of its compelling topic—medieval hygiene—or the ways it challenges stereotypes about the Middle Ages, but also because Janega’s sarcastic, comedic, and blunt tone are much more inviting to non-specialist audiences than academic writing. Following a synchronous in-class activity training my students to use Perusall, reading Janega’s piece constituted their first independent, asynchronous Perusall assignment. During the synchronous class meeting prior to the reading, as part of their annotations, I asked my students to share their general reactions to what they learned about both medieval hygiene specifically and Janega’s larger argument (that we need to both individually and systemically assess the misconceptions we bring into studying the Middle Ages). I also prompted students to think rhetorically about why she used the word choices she did, anxious to see how their discussion unfolded online. Below is a sampling of my students’ Perusall comments in reaction to this text:

- “How popular of a trade good was [soap]? Did it spread throughout all of Europe? We often have this image that during the medieval times, people couldn’t acquire any goods outside of their local area. Maybe that is also a myth.”

- “Reminds me of high school chemistry, we made soap with some kind of oil, really wasn’t that hard so it’s not that crazy that they had soap in medieval Europe”

- “Between the deodorant, the scented bathwater, and fancy soaps available, it seems like medieval folks might have had better bath times than me, haha”

- “It’s interesting how [Janega] keeps referring to the peasants as ‘regular ass people.’ I wonder if it is meant to make them seem like regular people from our time in order to draw parallels between these two times or if there is some other meaning to it.”

These student comments range from expressing a desire to learn more historical context about the topic, making personal connections based on prior experience, and analyzing the ways the author’s word choices inform her larger attempts to collapse the temporal divide between the medieval and the modern. Receiving such robust comments in an in-class discussion would delight any teacher; to receive them asynchronously during a year when eliciting student engagement was harder than ever opened my eyes to the real opportunity for class community-building that could be afforded even by asynchronous tools.

Connecting to the Premodern

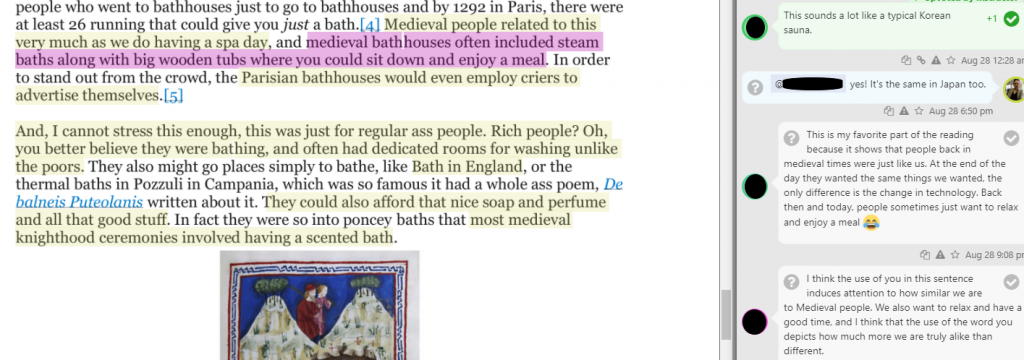

One benefit of using Perusall in a premodern class in particular is that helps students connect the topics to their own lives. While I’ve always encouraged my students to consider the relevance of premodern texts to contemporary issues, whether personal or systemic, it seems to happen more regularly on Perusall. In the comment chain in figure 3, for example, several students remarked on the comparison of medieval bathing culture to modern practices and the relatability of anyone wanting to feel refreshed and relaxed:

Figure 3: A student compares medieval practices to practices found in modern Korea

Similarly, in another Perusall assignment for the Old English poem “The Wife’s Lament,” one student remarked upon a passage that reminded her in tone of lyrics that Billie Eilish might write (the Old English poem reading, “Then I found that my most fitting man / was unfortunate, filled with grief, / concealing his mind, plotting murder / with a smiling face,” lines 18–21).

In both these examples, students’ analogical thinking collapses the line between the medieval and the modern. Medieval texts often strike students as alien. While there is a great deal of pedagogical usefulness to be found in that—such a sense of alienation forces students to rely on deep readings and contextual analysis, for example—an alienating experience of medieval texts can mean that the Middle Ages remain unrelatable to students. At best, students may come to see medieval studies as an interesting but isolated hobby. Encouraging regular analogical thinking, in contrast, helps students come to see how studying the premodern can also help them think more critically about the present. Furthermore, encouraging analogical annotations can help students develop empathy for people from whom they initially feel socioculturally and temporally divided. That is, while the role reading can play in developing empathy has been well documented, in the case of studying the premodern specifically, asking students to consciously look for personal connections while annotating medieval primary sources encourages an empathy with medieval peoples that can get students past the impulse to feel that “medieval people were all ignorant/superstitious/dirty/[insert your favorite pejorative here].”

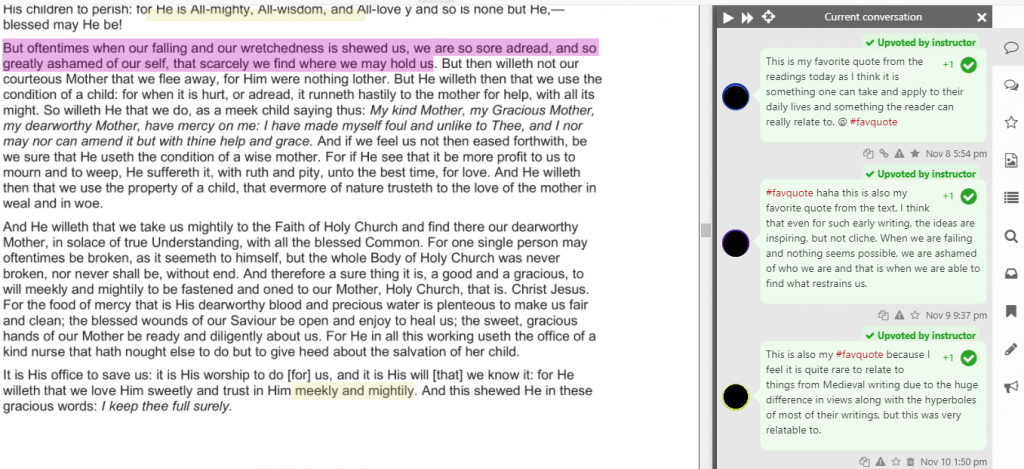

Tellingly, my students’ #favquote annotations demonstrate that they recognize that value of analogical thinking themselves, at least subconsciously. Many students justify their #favquote by explaining how the medieval passage parallels modern media that they enjoy, much like the above student did with Billie Eilish. One student, for example, identified a passage from Marie de France’s description in Bisclavret of popular (mis)conceptions of werewolves as their #favquote of the reading because it reminded them of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (de France writes that “A garwolf is a savage beast, / While the fury’s on it, at least: / Eats men, wreaks evil, does no good, / Living and roaming in the deep wood,” a stereotype that gets flipped on its head by the end of de France’s narrative, much like how Remus Lupin’s experiences in the Harry Potter series complicate binary conceptions of Human vs. Beast). Even more significantly, many of my students have identified passages in medieval texts that can help them navigate their own complicated lives as their #favquote. Figure 4 is a screenshot of one of the most notable examples, from a reading of excerpts of Julian of Norwich’s 14th-century mystic text, Revelations of Divine Love:

Figure 4: Students explore the relevance of Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love to their own lives.

In figure 4, multiple students remark upon the applicability to their own lives of Julian’s statement that “oftentimes when our falling and our wretchedness is shewed us, we are so sore adread, and so greatly ashamed of our self, that scarcely we find where we may hold us” (Chapter 61). Julian writes here about how contemplating self-perceived shortcomings creates a vicious circle of self-doubt and feelings of helplessness. It is perhaps unsurprising that students at a competitive, STEM-driven school would identify with a quotation that is essentially about imposter syndrome. What is remarkable is that students found solace from seeing a 14th-century writer express such a feeling, helping them to connect to the premodern.

Read Part 2 here (on 21 June 2021). If you would like to learn more about how Brittains integrate historical literature into the writing classroom see Mary Grace Elliot’s article on “Teaching Audience through Early Modern Literature” or Courtney Hoffman’s “Multimodal English Class: Elements of Eighteenth-Century Science.”

Works Cited

Bamburgh Research Project. “Kennings.” Bamburgh Research Project Blog, 21 June 2019, https://bamburghresearchproject.wordpress.com/2019/06/21/kennings/

British Library. “Julian of Norwich.” People, https://www.bl.uk/people/julian-of-norwich#

Campbell, Molly. “Feeling Like a Fraud: Imposter Syndrome in STEM.” Technology Networks, 7 October 2019. https://www.technologynetworks.com/tn/articles/feeling-like-a-fraud-impostor-syndrome-in-stem-324839

Cavell, Megan. “The Exeter Book Riddles in Context.” Discovering Literature: Medieval, British Library, 31 January 2018. https://www.bl.uk/medieval-literature/articles/the-exeter-book-riddles-in-context#:~:text=The%20bookworm%20riddle%20can%20be,as%20long%20as%2025%20pages.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “General Prologue.” The Canterbury Tales. The Riverside Chaucer, edited by Larry D. Benson, 3rd ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987, pp. 23–36.

Janega, Eleanor. “I Assure You, Medieval People Bathed.” Going Medieval, 2 August 2019, https://going-medieval.com/2019/08/02/i-assure-you-medieval-people-bathed/

Julian of Norwich. Revelations of Divine Love. Translated by Grace Harriest Warrack, Metheun & Company, 1907. Wikisource. 3 Jan 2021. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Revelations_of_Divine_Love

O’Hogan, Cillian. “The Classical Past.” Medieval England and France, 700–1200, British Library, https://www.bl.uk/medieval-english-french-manuscripts/articles/the-classical-past

Schmidt, Megan. “How Reading Fiction Increases Empathy and Encourages Understanding.” Discover Magazine, 28 August 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wy8rQFOLZHw

Schroeder, Ray. “Zoom Fatigue: What We Have Learned.” Inside Higher Ed, 20 January 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/blogs/online-trending-now/zoom-fatigue-what-we-have-learned

Turville-Petre, Thorlac. “What’s the Point of Studying Medieval Literature?” YouTube, uploaded by ArtsPoint, 2 April 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wy8rQFOLZHw

“The Wanderer.” Translated by R.M. Liuzza. Old English Poetry: An Anthology, edited by R.M. Liuzza, Broadview Press, 2014, pp. 28–31.

Wiest, Lynda R. and Kellie J. Pop. “Guiding Dominating Students to More Egalitarian Classroom Participation.” Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, March 2018, pp. 1–6. https://kpu.ca/sites/default/files/Transformative%20Dialogues/TD.11.1.9_Wiest&Pop_Guiding_Dominating_Students.pdf

“The Wife’s Lament.” Translated by R.M. Liuzza. Old English Poetry: An Anthology, edited by R.M. Liuzza, Broadview Press, 2014, pp. 41–42.