By Kendra Slayton

Closing Distances

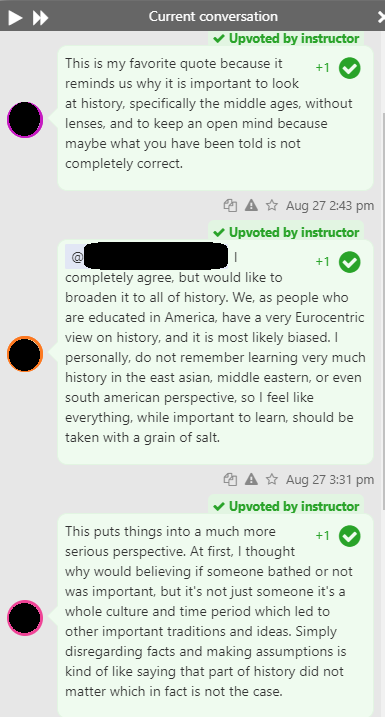

Figure 5: Students theorize why medieval peoples are stereotyped as unhygenic despite material evidence of robust medieval bathing practices

In addition to helping students close the distance between the premodern and the modern, Perusall has been an invaluable tool for building a sense of community in my remote classroom. Students quickly begin to form comment chains, debating the meaning of the texts and the historical phenomena they are studying. Figure 5, for example, shows annotations that students added to the beginning of Janega’s piece about medieval bathing, to a sentence that reads, “In fact, medieval people loved a bath and can in many ways be considered a bathing culture, much in the way that say, Japan is now”:

Impressively, in figure 5’s annotations, students are not merely including their personal reactions but are engaging directly with each other in each subsequent reply—not a requirement of their Perusall annotations, but something that has happened organically again and again with each annotation assignment. In the first comment, a student notes the dissonance between the archaeological material they’ve been presented with in the article and the stereotypes of an unhygienic Middle Ages that they brought into the reading assignment; the comment falls somewhat ambiguously between expressing awareness of how problematic periodization stereotypes can be and expressing skepticism of Janega’s argument, given that (in the student’s personal experience to date) they’ve never seen bathing mentioned in medieval sources. In the second comment, another student points out that in our own lives, we don’t necessarily think to document mundane activities like bathing, focusing instead on more novel experiences. Finally, a third student, mediating between the first two, rightly supposes that many of us probably have encountered documentation of hygiene practices in medieval sources but that we are also likely to overlook such documentation if we’re not explicitly looking for it. In this particular thread, students work together to achieve a more nuanced understanding not only of this singular secondary source but also of the significance of material evidence and primary sources, and of the problematic nature of historical generalizations.

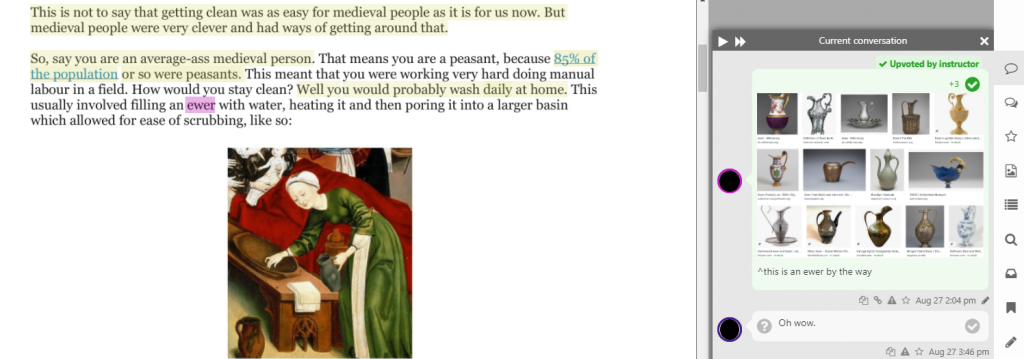

Students also—unprompted—tend to help each other understand the readings better by sharing research with each other, even though they are not doing so in “real time” while physically together in a classroom. For example, one student annotated a sentence referring to a bathing ewer with images she had looked up in order to better comprehend the passage:

Figure 6: A student shares photographic examples of medieval bathing ewers to help illuminate a term (highlighted in purple) found in the reading

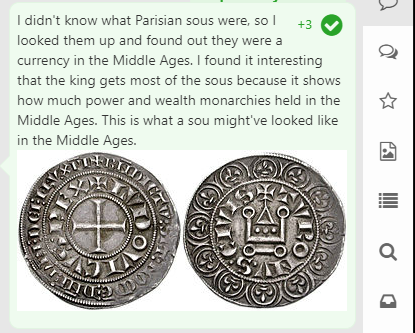

Another student took a similar approach when they encountered a reference to the medieval currency “Parisian sou.” Like with the student who shared examples of medieval bathing ewers, this student—again unprompted—relied upon multimodality in their response, sharing their research with a written description and an image of a medieval artifact, demonstrating an impulse towards modes that help bring history to life:

Figure 7: A student shares a photograph of a medieval Parisian sou, a unit of currency referred to in their secondary-source reading.

In addition to helping students build rapport amongst themselves—something many of them have been sorely missing during the pandemic—Perusall also helps me engage with my students. For example, while I usually give students a chance to answer each other’s questions first, I can step in as needed, as seen in the last comment in figure 8’s debate about the efficacy of medieval soap made from animal fat:

Figure 8: Responding to the sentence highlighted in purple, students debate the efficacy of medieval soap, and are encouraged by their instructor to consider alternate ways to frame this topic.

Figure 9: Students remark upon the importance of countering historical stereotypes and expanding their perspectives

In the example, students have begun to come around to the idea that medieval people did, in fact, bathe (the central point of Janega’s piece) but still expressed resistance to the idea that this bathing could have been at all effective. This was an indication, perhaps, that they were on some level having trouble letting go of the “medieval people were filthy” stereotype that so many people have, even in the face of evidence to the contrary presented throughout the article. In this particular case, however, students were dancing around central but unasked questions—what are the standards for measuring the efficacy of soap? How often do we judge the ingredients in our hygiene and beauty products today? In cases such as this, Perusall makes it easy for students to lead the way in discussion and for teachers to gently step in, as needed, and provide further points for deliberation in order to nudge students’ critical thinking even deeper. By the end of the reading, many students were persuaded not only of Janega’s central thesis but of why it matters—in figure 9, for example, several students remark upon larger biases in history and education and of the importance of expanding our perspectives by studying other time periods and cultures, reacting to the closing line of the article: “If we always blame medieval people for everything difficult it allows us to deny their humanity and write off a thousand years of thinking and culture that still influences us now.”

In this way, even during asynchronous days, I am able to replicate with my students the kinds of organic, community-building exchanges that occur during whole- and small-group discussions in traditional face-to-face meetings, even if our work is entirely asynchronous on that particular day. And in many ways, as with the above examples, our exchanges, whether just between students or between myself and students, are even more robust than an in-person class discussion could afford, contributing profoundly to student’s growth in expertise in the class’s subject, as asynchronous annotation allows for more measured, deliberate, and researched responses.

Creating Deeper Discussion

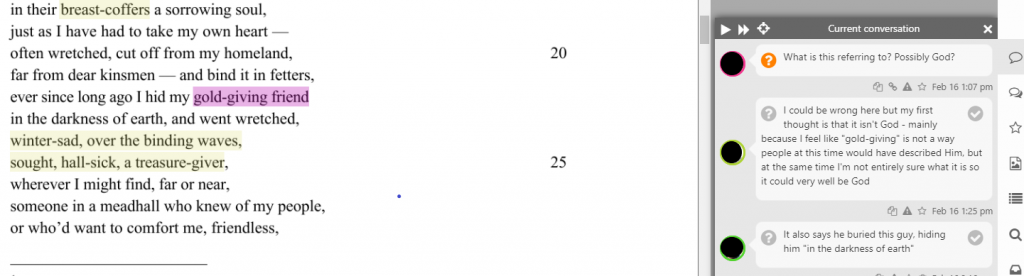

Likewise, the act of group annotation fosters development of close-reading skills by encouraging students to consider individual word choices and phrases throughout the text, which can turn set students up to have deeper discussions. In the following passage from the Old English poem “The Wanderer,” for example, students helped each other parse the meaning of the kenning “gold-giving friend:

Figure 10: Students debate how to interpret the riddle-like phrase “gold-giving friend”

In this exchange, the students essentially remind each other that in order to correctly parse a kenning, they must consider how the phrase works in conjunction with the entire passage—much like solving a riddle, which we had practiced in the previous class with Old English riddles from the Exeter manuscript. In this case, the kenning “gold-giving friend” must have a meaning that works in conjunction with the rest of the passage. The first student’s guess, “God,” could work in a metaphorical sense if read in isolation, taking God to be the source of all human success and prosperity. As the second and third students point out, however, this interpretation makes less sense when one considers that in this specific passage, the “gold-giving friend” must be someone who the speaker “hid…in the darkness of earth”—that is, buried. While the students did not quite come to the correct solution (king) in this specific thread, they did help each other narrow down the possibilities by reminding each other of the importance of whole-passage context clues when interpreting texts.

Such close reading, enabled by annotation, helps students feel better prepared for both in-class discussions on our synchronous days and larger projects by ensuring that they’ve already read the relevant materials carefully. Asynchronous use of Perusall is particularly effective for facilitating later synchronous discussions when used in conjunction with “thinking questions”—that is, for some readings, I let them know a few of our in-class discussion topics in advance, so that they can be on the lookout for related themes while they are doing the reading. Students have reacted favorably to such uses of Perusall in both their course evaluations—where it was one of the most common responses when students were asked to identify the “course best aspect”—and in their final portfolios. One student, for instance, wrote in their portfolio that not only did Perusall help them practice their written communication skills, but that in addition,

All of this written preparation was very useful during the in class small group discussions. During this time, I was able to use the written material I had produced earlier on in order to discuss the questions we were given in class.

Another commented that “Perusall was one of the best ways to learn better analysis skills” and that it helped them to more fully understand the medieval texts because

it created a way for the class to have discussions on our reactions to the text. Many times, I would get lost or confused in parts of the text and this software was great because there would always be someone else confused at the same part as me and I could find an explanation nearby. This also allowed me to read what other people thought about certain scenes or dialog and opened up new perspectives for me to appreciate.

Finally, yet another student specifically pointed to Perusall for boosting their overall confidence, explaining that

Using Perusall, I was able to communicate with classmates about the texts, leaving and responding to questions and comments in order to promote a better understanding of the texts for the class as a whole. While I was timid to ask questions in this manner at first, my confidence increased proportionally to my knowledge and understanding of my classmates. Each of our unique experiences allowed us to leave questions to improve our own understanding, answers to aid classmates’ understanding, or comments about interpretations and reactions that brought the text to life.

As much as asynchronous Perusall work helps students feel better prepared synchronous class activities, the reverse is also true—as a teacher, being able to review students’ annotations helps me see what students want to talk about more and what is confusing them. Perusall can in this way become a tool to help me refine my lesson plans as much as it is a tool for helping students build a sense of community and deepen their understanding of the texts. For example, when reading the first part of Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale, which was written in 14th-century England but takes place in classical Greece, several students expressed confusion at seeing terms like “duke” used instead of “king,” as well as at seeing the names of Roman Gods invoked throughout the tale instead of Greek Gods. Seeing these comments, I adapted my lesson plan for our next synchronous course to include both some explanation of the phenomenon of medieval classical “fan fiction”—something quite surprising for students to learn since it counters the misconception that classicism was only revived in the Renaissance—as well as to explain the historical transmission of classical Greek legends through Latin texts and translations.

Conclusion

But of all the affordances Perusall offers, the greatest is that it helps ensure that a diversity of student voices are heard throughout the semester. As many teachers have experienced, in traditional in-person discussions (and even online synchronous discussions), it is all too easy for five to six of the most outspoken students to dominate, despite instructors’ best efforts. An asynchronous annotation tool, however, gives a platform to even the shiest of students, and increases students’ confidence in their participation by removing some of the anxiety that on-the-spot Socratic seminar can create. Furthermore, such students are in turn more likely to participate even in synchronous class discussions because the act of annotating has helped them to preemptively think through the text and jot down their main responses and impressions before in-class discussion begins. For this and for the many other benefits to critical thinking and metacognition that annotation offers, I plan to continue using Perusall even after my return to face-to-face teaching. In addition to continuing to combine asynchronous Perusall annotation assignments with “thinking questions” that help prepare students for later discussions, I plan to integrate Perusall activities directly into in-class activities as well—for example, by asking students to work in groups to (re)annotate particularly difficult or important passages of longer texts and then to have them present a summation of their interpretation of the passage and its larger connection to the day’s topic to their classmates. While I initially perceived Perusall to be a tool I could rely on temporarily to replicate an in-person class, I now look forward to continuing to use it as a means for increasing the equity of class discussions whether asynchronous or synchronous; boosting student confidence; and developing a sense of rapport that extends beyond the physical classroom.

If you would like to read more about digital tools in the writing class room, see Lizzy LeRud’s article on the poetry tools, Gentle and Drift, or Danielle Gilman’s article on teaching with archives.

Works Cited

Bamburgh Research Project. “Kennings.” Bamburgh Research Project Blog, 21 June 2019, https://bamburghresearchproject.wordpress.com/2019/06/21/kennings/

British Library. “Julian of Norwich.” People, https://www.bl.uk/people/julian-of-norwich#

Campbell, Molly. “Feeling Like a Fraud: Imposter Syndrome in STEM.” Technology Networks, 7 October 2019. https://www.technologynetworks.com/tn/articles/feeling-like-a-fraud-impostor-syndrome-in-stem-324839

Cavell, Megan. “The Exeter Book Riddles in Context.” Discovering Literature: Medieval, British Library, 31 January 2018. https://www.bl.uk/medieval-literature/articles/the-exeter-book-riddles-in-context#:~:text=The%20bookworm%20riddle%20can%20be,as%20long%20as%2025%20pages.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “General Prologue.” The Canterbury Tales. The Riverside Chaucer, edited by Larry D. Benson, 3rd ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987, pp. 23–36.

Janega, Eleanor. “I Assure You, Medieval People Bathed.” Going Medieval, 2 August 2019, https://going-medieval.com/2019/08/02/i-assure-you-medieval-people-bathed/

Julian of Norwich. Revelations of Divine Love. Translated by Grace Harriest Warrack, Metheun & Company, 1907. Wikisource. 3 Jan 2021. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Revelations_of_Divine_Love

O’Hogan, Cillian. “The Classical Past.” Medieval England and France, 700–1200, British Library, https://www.bl.uk/medieval-english-french-manuscripts/articles/the-classical-past

Schmidt, Megan. “How Reading Fiction Increases Empathy and Encourages Understanding.” Discover Magazine, 28 August 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wy8rQFOLZHw

Schroeder, Ray. “Zoom Fatigue: What We Have Learned.” Inside Higher Ed, 20 January 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/blogs/online-trending-now/zoom-fatigue-what-we-have-learned

Turville-Petre, Thorlac. “What’s the Point of Studying Medieval Literature?” YouTube, uploaded by ArtsPoint, 2 April 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wy8rQFOLZHw

“The Wanderer.” Translated by R.M. Liuzza. Old English Poetry: An Anthology, edited by R.M. Liuzza, Broadview Press, 2014, pp. 28–31.

Wiest, Lynda R. and Kellie J. Pop. “Guiding Dominating Students to More Egalitarian Classroom Participation.” Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, March 2018, pp. 1–6. https://kpu.ca/sites/default/files/Transformative%20Dialogues/TD.11.1.9_Wiest&Pop_Guiding_Dominating_Students.pdf

“The Wife’s Lament.” Translated by R.M. Liuzza. Old English Poetry: An Anthology, edited by R.M. Liuzza, Broadview Press, 2014, pp. 41–42.