“Burnt out Bonito Park with Schultz wildfire still burning in the peaks behind” (2010) by Deborah Lee Soltesz

My English 1102 class this semester, “Sovereignty, Energy, and Settler-Colonialism,” examined the historical relationship between Native Americans, American politics, and the demand for energy through the lenses of settler-colonialism and environmental justice. In other words, we investigated the ways energy and fuel have been a rationale for the marginalization, removal, and murder of Native Americans. We studied a few specific moments in Native American history—the Indian Removal of the 1830s, the uranium mining and nuclear testing on Native lands in the mid-twentieth century, and the modern resistance to fossil fuel infrastructure on Native lands, including movements like the #NoDAPL protests of 2016/17—with the goal of understanding how the energy wealth of settler societies is often predicated on the energy poverty of indigenous communities.

These course themes were intended to echo the very building where we were learning: the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design. The Kendeda Building opened for classes in January of this year, and my courses were among the first to be held inside. A “Living Building” (a certification like LEED) is designed to be environmentally regenerative; Kendeda produces its own power and water while embracing biophilic design. Being a Living Building, though, is more than just a matter of technology and design. The Living Building Challenge has a number of imperatives (termed “petals”), four of which are socially oriented. I wanted my students to analyze how the building’s social imperatives—equity, health, place, and beauty—parallel Native American philosophy, to show how some theories of environmental justice are not new and how settler societies repackage indigenous knowledge.

“Kendeda Building in Winter” (2019) by Kent Linthicum

For the final assignment of the class, I challenged my students to create multimodal research projects that embraced environmental justice and engaged with Native peoples’ history, culture, and ideas. As 1102 is the last composition course students at Georgia Tech take, I wanted them to apply their knowledge of medium, genre, and audience by building a project from the ground up. Each project had to go through multiple rounds of approval, including initial brainstorms and formal proposals. Ultimately, my goal was that students not only make projects for the course, but also share their projects with the Georgia Tech community. Like so many things, though, my goal was stopped short in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article represents my attempt at resilience. I strive to teach resilience in my first-year composition courses. Composition, the process of writing, receiving feedback, revising, editing, and seeking more feedback, requires the ability to be adaptable to change and stress. Being a college student, managing deadlines, projects, and life, requires it. The ever-growing crisis of climate change requires it. Our global health emergency requires it.

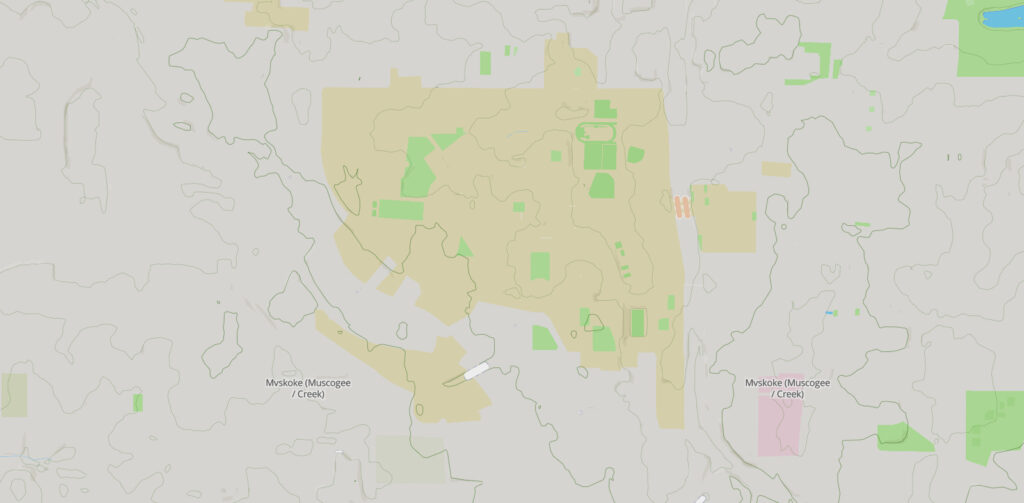

I had wanted to work with my students to place their projects in the Kendeda Building and around Georgia Tech, to make the research they had done visible to the campus. As I told my students a number of times during class: the Kendeda Building and Georgia Tech are built on Muscogee (Creek) lands ceded under duress in the Treaty of Indian Springs of 1821 (Green 73–5).[1] Yet there is no acknowledgement—symbolic, remunerative, material, or otherwise—that these lands were ever lived on and tended by the Muscogee, that Georgia Tech, in part, owes its existence to the Muscogee people.

a map of Georgia Tech on Muscogee land from Native-land.ca

In prompting students to resist the strategic forgetting of settler-colonialism, I gave them the opportunity to facilitate, in their own ways, acknowledgements of Native peoples and cultures (Whyte 135). But now, at the term’s end, the campus is empty of most students, staff, and faculty. The remaining population is made up of stranded students, staff members who are being asked to risk their lives for their jobs, and animals taking advantage of the sudden freedom. I couldn’t ask my students to put up posters, film videos, or host events. Rather than give up on my goal, I wanted to try and accomplish some of what I had intended. Therefore, this article acts as a digital showcase to highlight my students’ work. Below are five student projects from my class that grapple with the lives of Native peoples, environmental justice, and climate change. These projects show students at a technological university driven to help create a more just, equitable, and sustainable world.

“Hawaiian Sovereignty and the Threat of the Thirty Meter Telescope” by Gard, Julia, Madeleine, and Taylor

In this podcast, Gard, Julia, Madeleine, and Taylor contextualize and analyze the controversy surrounding the Thirty Meter Telescope, describing the ways the telescope impinges on the sovereignty of Native Hawaiians and duplicates colonial attitudes towards Hawai`i. This is a challenging topic because unlike the #NoDAPL protests against oil pipelines, telescopes are seen to be benign, if not positive, infrastructure. Science and technology are often framed as unqualified goods, which is especially true at Georgia Tech. This is what makes Gard, Julia, Madeleine, and Taylor’s podcast so fascinating: they challenge that assumption. They do not reject science or technology; rather they question the application of science and technology through thorough research and critical thinking. They argue that science and technology should serve, engage, and respect all people. Their argument is exceptional, and accordingly was awarded both the William Gilmer Perry Award for first-year writing and the Diversity in Creativity and Research Award by the School of Literature, Media, and Communication.

“The Reality of Native Exploitation” by Amy, Imoh, Jeyan, Josiah, and Zeyu

“Climate Change in the Pacific” by Annabelle, Devanshi, Gunnar, and Will

Annabelle, Devanshi, Gunnar, and Will had a clear desire to focus on the Pacific from the start of the project. Their real question was medium: was it better to make a video, podcast, poster, or something else? After talking about it, they decided on a video. And then campus closed. So Annabelle, Devanshi, Gunnar, and Will switched to a podcast. Though the team was spread far apart in their home cities, they produced a comprehensive podcast series focused on the Pacific, specifically the Marshall Islands and Hawai`i. The complexity and breadth of their research stand out to me, connecting the effects of colonialism and nuclear testing with climate change. I also admire the call to action in the final episode: they emphasize that mere listening is not enough and that we (specifically young people) need to act as the climate crisis intensifies.

“Rewriting History: Exxon v Kivalina Edition ” by Alex, Madison, and Tam

Pages 1, 6, and 20 from the project

Alex, Madison, and Tam had a complicated transition from working in-person to online. Their initial project was a website on the effects of climate change, and their team was large. Due to circumstances beyond their control, the team shrunk, and the website was thrown out the window. Eventually, over spring break they settled on creating a game inspired by the Reacting to the Past role-playing game, Red Clay: Cherokee Removal and the Meaning of Sovereignty (2018), which we played earlier in the semester. Alex, Madison, and Tam focused their game on the Iñupiat city of Kivalina and its lawsuit against ExxonMobil. The people of Kivalina sued ExxonMobil because their home is being destroyed by the rising sea levels caused by ExxonMobil’s more-than-100-year history of extracting and burning petroleum. The game counterfactually re-imagines the court case (which in reality was thrown out on jurisdictional grounds) and asks the players to debate climate change and distributed responsibility. I enjoy the creativity of this project: rather than asking users to consume information, this project asks users to inhabit a situation and make arguments about the values we want to, and should, hold.

“Going Green: Indigenous & Western Sustainable Building” by Daryl, Grayson, Jack, and Yi

In this podcast, Daryl, Grayson, Jack, and Yi analyze green-building standards, the Kendeda Building, and Native American architectural practices. They had originally intended to film a video, and were planning to shoot footage of the Kendeda Building only days before Tech closed. After I consulted with the team on our final day, Daryl, Grayson, Jack, and Yi pivoted to a podcast. What sticks out to me about this project is the depth of research, especially in regards to the building practices of the Muscogee people prior to colonization. The students excel in situating that research among Kendeda’s design and (even more importantly) philosophy. This team extends the class’s examinations of the Kendeda Building’s lack of place, and ultimately argues in favor of placing the building within a deeper historical context by inviting the Muscogee to Kendeda to speak about their history and culture, or even give poetry readings (such as inviting the current poet laureate of the United States, Joy Harjo, who is Muscogee). This podcast serves as a call to more thoroughly contextualize Georgia Tech in environmental and cultural history.

Despite the challenges of this moment, these students showed resilience in their work and thinking. Their projects all demonstrate a willingness to confront not merely the scientific or technological dimensions of the crises we face today, but also the human dimensions of culture, justice, and equality. This generation of students, as the COVID-19 pandemic makes clear, is going to face a dramatically different, much more uncertain world, especially as climate change worsens. Yet, as I have seen in their exceptional capacities for adaptation, they are willing to struggle with those challenges to seek a better world.

[1] Tech is also not far from Cherokee lands, maybe two and a half miles (“Native Land”). Given that Native peoples did not historically define their land based on drawing lines on maps, it is not impossible to imagine that the Cherokee might have also tended the land Tech occupies currently. Moreover, given Georgia’s history with the Cherokee, there is I think a good argument for including the Cherokee in any acknowledgements on Tech’s campus.

Works Cited

Green, Michael D. The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis. University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

“Native Land.” Native Land Digital, 2020. native-land.ca

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Ceremony. 1977. Penguin Books, 2006.

Weaver, Jace and Laura Adams Weaver. Red Clay, 1835: Cherokee Removal and the Meaning of Sovereignty. W.W. Norton, 2017.

Whyte Kyle. “Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research, vol. 9, 2018: 125–144. doi:10.3167/ares.2018.090109